Johannes Pingilina, a Dieri speaker from Bethesda mission in South Australia was central to the outreach at Elim (Cape Bedford) and Bloomfield (later Wujal-Wujal). The missionary literature on Queensland pays little attention to native evangelists, and Pingilina has been all but erased from the memory of these two missions. Lay missionaries in general are poorly documented in the missionary archives, so that the information available about Johannes Pingilina is patchy. This account is pieced together from the correspondence extant in the Lutheran Archives in Adelaide, which however contains many gaps. It demonstrates how Pingilina felt isolated and was trying to be taken seriously as a member of the mission staff, but received barely an acknowledgement for his evangelising efforts. Only after World War II did native evangelists play an acknowledged role in Cape York missions.

From Bethesda to North Queensland

|

|

.jpg) |

|

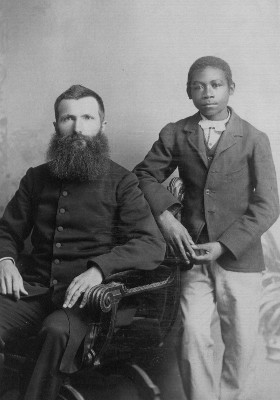

For many years it was thought that this was a photograph of Johannes Flierl with Pingilina.

But the indigneous boy has little resemblance to the adult portrayed right.

It is more likely that this photo was taken during Flierl's visit to South Australia

accompanied by Biwa, a young boy from Papua New Guinea mentioned in

Flierl's autobiography. This ascription has now been agreed by the Lutheran Archives

and Susanne Froehlich, a German descendant of Flierl.

Source: M00278 Lutheran Archives Australia |

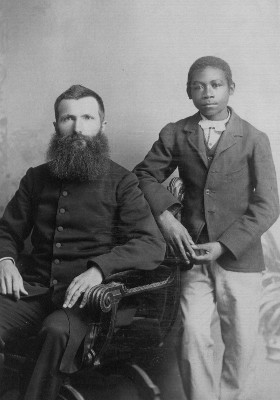

Johannes Pingilina and his wife Rosie

Source: M00290Lutheran Archives Australia

|

Johannes Pingilina belonged to the ‘first fruit’ of baptised Christians at the Dieri mission at Coopers Creek in 1879, when Christian names were added to the indigenous name instead of replacing the former name. He had a daughter Maria in 1880 and his one-year old baby Emma succumbed to an influenza epidemic in 1885. He became a champion clip-shearer at the Etadunna sheep station attached to the mission.

[1] Because of his linguistic abilities he was sent in company with Rev C.A. and Mrs Meyer to the newly acquired Immanuel Synod mission at

Cape Bedford in June 1886. He commenced learning Guugu Yimidhirr and helped Meyer to learn the language. After Rev. Georg Pfalzer arrived in September 1886, they reputedly taught some 30 children together in Guugu Yimidhirr. After less than a year at Elim he shifted with the Meyers to

Bloomfield arriving on 21 May 1887, and had to immerse himself into yet another language.

At Bloomfield in 1887 Pingilina started a courtship with the indigenous kitchen hand but the relationship foundered on the cultural differences between them, where Pingilina strove to lead a Christian and monogamous life, and he found the woman too much immersed in camp life. Faced with the difficulties of living in close proximity after a failed relationship, Pingilina wanted Meyer to dismiss the woman, and in vain appealed to mission director Rechner in South Australia for intervention. By December 1887 he had left Bloomfield and returned to Cape Bedford, where he worked with Rev. Schwarz who had arrived in September that year. Meyer at Bloomfield soon complained that he was missing Pingilina’s help as a translator, and that he was unable to make much progress with the Kuku Yalanji language without Pingilina’s help

.[2]

Meyer succeeded in getting Pingilina back to Bloomfield at some time in the first half of 1888. By June 1888 Pingilina asked why it was that all other mission staff were getting paid, but he was not. Meyer suggested that £5 per year might be set aside for him and held in trust

.[3] Pingilina wrote to the mission committee, as usual in Dieri language, roughly translated by Meyer, explaining the work he was doing among the local people, the difficulty of spreading the gospel of love among people who dismissed it as mere talk, affirming his commitment to the faith, and he also inquired about the money that was being held in trust for him, since he was about to marry. His countenance in such letters is very much that of a missionary shouldering responsibilities. In his letters he used the traditional respectful address of ‘older brother’, calling himself ‘younger brother’

.[4]

After two years of work as an evangelist in North Queensland, Pingilina married the young Aboriginal woman Rosie who had been brought from Cooktown. This was the first time the Anglican pastor in Cooktown had married a black couple, and he did so free of charge. Meyer observed how much effort it had been to organise the whole event and outfit both of the couple with a set of clothes for the occasion, and to have a photograph taken in a Cooktown studio

.[5]

Nine months after his wedding, Pingilina wanted to take Rosie to New Guinea to join missionary Johann

Flierl at Simbang. He had known Flierl since childhood, and most likely met up with him during Flierl’s visit at Cape Bedford in late 1887. It is also possible that he wished to distance himself from Meyer, whom he observed to be frequently inebriate, and that he may have hoped to bind Rosie closer to him by separating her from Aboriginal communities.

This proposal was considered outrageous. The Queensland authorities were not likely to permit the overseas travel of an Aboriginal woman, and intervened with the mission committee in Adelaide, which in turn severely censured Meyer about the ‘Pingilina affair’. Meyer was deeply affronted, and ‘plainly speaking tired’, and offered to retire if the committee thought him incapable of supervising the mission

.[6]

I don’t know what I am

Pingilina was forced to remain at Bloomfield, which was bristling with tension between the white staff. At the end of the year this tension came to such a head that Meyer really did resign, and the committee sought information from the staff members individually. They closed ranks and refused to give information, saying all had been smoothed over again. Whether or not Pingilina was asked to comment, he gave his account through Rev. J. Flierl II at Hergott Springs, who translated and forwarded his letter in April 1890. Pingilina asked that his account be treated confidentially, unlike his earlier report which was leaked back to Bloomfield and caused much strife for him. He confirmed the reports received by the authorities that lay missionary Jesknowski was unpopular with the Bama, and that it would be best if Jesnowski left. He described the constant bickering between Meyer, Jesknowski, Koch and Steicke and wondered what his role is among the staff: ‘and me? I don’t know what I am. I am just me.’

Johannes Pingilina at Bloomfield to Rev Rechner in South Australia, via Hergott Springs, 29 April 1890:

Yes, Jesnowski shows himself to be a hypocrite, here, in Cooktown and everywhere. He thinks himself very clever but does not want to work at all, very lazy and sleepy he is. Many whites also don’t like him. Last year Mr Meyer told Jesnowski to teach the children praying and singing, just that is what Jesnowski has not done. … And more: recently I secretly observed that they are always drinking, drinking and afterwards arguing. And so several people make jokes about the head of the station. You know who. This is what I am telling you but I don’t want it to be spread around. Mr Koch is friendly. Mr Jesnowski has two faces. Mr Steicke is friendly. Mr Meyer indulges them. So Koch and Steicke and Jesnowski talk about him. Hearing and realizing such things they had a fight last year. And me – I don’t know what I am. I am just me . …. Many times I have thought of running away from them. It would be very good if Jesnowski had to leave here. Afterwards the mission station would be better. Do not spread around such talk. Last year I also complained to you and you returned my talk. (So what have you perpetrated with that.) …. I yearn to help the missionaries. If only you might allow Mr Flierl in New Guinea to help Mr Meyer here. At present Mr Meyer is not very healthy. …. Such things I hate very much when there is always argument at the station. And may Jesus help to work better through his spirit. God the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost be with us.

Your younger brother,

J. Pingilina

Another year passed, and Meyer became increasingly incapable of work from sickness, asking for an assistant missionary. The mission was disintegrating. Jesnowski and Steicke left, and negative reports about Meyer reached the Chief Secretary.

Pingilina’s marriage also deteriorated. In February Pingilina wrote to Rechner that he was longing for his home and language environment. His wife had run away to the Aboriginal camp, and he had to suffer the taunts of his fellow workers. Pingilina blamed the unfriendly treatment Rosie had received from Mrs. Meyer, whereas Meyer reported that Rosie refused to obey her husband, that they had been having arguments, and that he had no talent to bind her to him. In March Steicke joined forces with Pingilina in a last-ditch attempt to persuade Rosie to come back, but she refused. Quite possibly the marriage breakdown was a result of Pingilina’s homesickness and his plans to return to Bethesda in South Australia.

Pingilina was now in a difficult situation, legally married and doomed to celibacy. He inquired about the possibility of a divorce and in August 1891 Meyer reported that he had obtained legal advice that it was safe for Pingilina to remove himself to South Australia where it was unlikely that his wife would legally pursue him.

[7] It sounds like off-the-cuff advice from a lawyer who did not take Pingilina’s situation very seriously. Surely the problem was not that his wife might legally pursue him, but that he might be prevented from remarrying by the missionaries, or have the charge of polygamy laid by the government.

Pingilina was clearly having trouble getting taken seriously as a native Evangelist – ‘I don’t know what I am. I am just me.’ He was pining for home, and Meyer started to find him difficult: ‘full of pride’, and ‘wanting to be respected by all whites’. Meyer related an incident which was supposed to show how inflated Pingilina’s sense of his own importance had become. Mrs Meyer asked him to put his chair back after the meal, as was the custom, and he replied ‘don’t you have hands any more to do it?’

[8] A small incident, and pregnant with insubordination.

What should happen with Pingilina?

The Meyers were Pingilina’s ticket out of Bloomfield, and Meyer kept inquiring ‘But what should happen with Pingilina? He desires to go back home.’

Meyer himself was getting stood down because word of his drinking habit had reached the Queensland government. A whole new change of shift was taking place at the mission from 1891 to 1892. Missionary Hörlein arrived and all three German lay helpers left. Hörlein soon realized how useful Pingilina was for the mission and implored the mission committee to send him for a spell to Bethesda with the brief to return after six months. Hörlein argued that Pingilina’s only wanted to leave because Mrs Meyer had treated him unkindly. But Meyer corrected this view: Pingilina ‘wants to see his Maria again and speak his own language’.

[9]

After this there is seven-year gap in the Bloomfield correspondence, and Pingilina does not reappear. He does receive a mention in the Bethesda records. According to Stevens, by the time Pingilina arrived back at Bethesda his daughter had already died. Meyer left Bloomfield in 1892, and Maria died in 1895, so it is possible that Pingilina was after all not allowed to return with Meyer. In 1902, as Rev. Siebert prepared to leave the mission, Pingilina was among his faithful supporters

.[10]

[1] Stevens, Christine White Man’s Dreaming: Killalpaninna Mission 1866-1915, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 115, 122, 138.

[2] 28 January 1888 Meyer to Rechner, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[3] 14 June 88 Meyer to Rechner, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[4] 9 July 1888 Meyer to Rechner, attaching letter from Pingilina, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[5] 15 July 1888 Meyer to Rechner, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[6] 12 June 1889 Meyer to Rechner, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[7] 7 August 1891 Meyer to Rechner, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[8] 7 August 1891 Meyer to Rechner, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[9] 28 December 1891 Meyerto Rechner, Bloomfield correspondence, Lutheran Archives Australia.

[10] Stevens, Christine White Man’s Dreaming: Killalpaninna Mission 1866-1915, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 122, 257.

.jpg)