Flierl, Johann (1858-1947)

Prepared by:

Regina Ganter

Johann Flierl was the epitomy of the successful German missionary. From a farm in Bavaria, he trained at Neuendettelsau with an early and strong sense of vocation. He was quick to spot opportunities for strategic development. During his period at Bethesda mission at Killalpaninna (1878-1885) Germany acquired territory in New Guinea, and he immediately proceeded to become the first Lutheran missionary in this new contact zone. Along the way he was briefly delayed at Cooktown and used this time to start another mission at Cape Bedford, which he called Elim. He spent the next 44 years as a missionary in New Guinea (1886-1930) where his four children were born, developing a network of missions, and retired at age 72.

Table of Contents

| Rev. Johann Flierl |

| Source: M00278, Lutheran Archives Australia |

Early life

Johann (Hansel) was born on 16 April 1858 at Buchhof (then consisting of three houses) in the Upper Palatine, near Nürnberg. He went to the local public school at Sulzbach for seven years, until age 14. His autobiography gives glimpses into rural village life of thatched roof cottages with open wells presenting dangers. Matchsticks were still a novelty (introduced to Germany in the 1830s), and the family ate from one bowl, using a slice of bread as their plates. Hansel learned knitting from his father, and could finish a sock in a day. Bavaria had been at war with both Prussia and France, and both were equally considered foreign countries until the French defeat and unification of Germany under Prussia in 1871. The railway networks were just getting extended, and for people like Hansel, who could neither ride nor shoot, walking was the mode of transport. Family was the only support network, and after his sister died her widower married another sister in the Flierl family. Superstitions and spiritism – the belief that the devil could manifest himself – suffused the Christian beliefs of the mostly Catholic villagers. Bavaria was not much affected by the ‘Kirchenstreit’ that fragmented Protestants in Prussia. In Sulzbach the Protestants even reached a convivial arrangement with the Catholics, by installing a submergible altar in the Catholic church, which could be hauled up for Protestant services.[1]

Flierl attended the Sunday school of the local Protestant pastor who recommended him for Neuendettelsau. He first went into apprenticeship with a blacksmith in Nürnberg, but when his father found out that they were made to work on Sundays, he promptly picked his son up again after just three weeks, and tried to place him in the college, where they were told that Johann had to be at least 17 to enter the college. He had to wait four years until he was accepted in 1875. He appears to have had the solid support of his parents in his missionary aspirations, and this gave him a strength of character that made him sometimes difficult to manage by his later employers.

At this time the graduates were sent only to the German communities in Australia and America. It accepted small cohorts every year, so that a strong bond formed between the graduates. The students were encouraged to nurture the link between the institution and its financial supporters by visiting them during the September and March holidays.

A call for missionaries was received from South Australia, and Flierl eagerly volunteered before he had completed even half of his time at the seminary. He completed his three years and was then sent to Australia, destined for Cooper Creek (Bethania).

Flierl’s departure for Australia must have been quite an occasion in the family, and inspired two of his cousins to also enter the seminary. Konrad Flierl, born in 1865 in Sulzbach, was just 13 when his cousin left for Australia, and entered Neuendettelsau the following year in the preparatory course. He spent five and a half years at the seminary and was sent to the USA in 1885.[2]

| The Flierl family home at Buchhof |

|

| Source: Flierl 1999 |

Cousin Johann Flierl (II), also born in April 1858, had learned farming from age 14 to 17, then completed an apprenticeship in carpentry, then worked in a mine. During the period which Johann (I) spent anxiously waiting for his admission to the seminary, reading only wholesome books, getting tuition from local priests, and often getting teased for his piousness, his cousin Johann (II) caroused in Nürnberg. His first thought of becoming a missionary arose when Johann (I) departed to Australia in 1875. He was accepted into Neuendettelsau in spring 1880, while Konrad was there, and sent to Australia three years later.[3] He was called as a replacement for his cousin to Cooper Creek in late 1883 and married a girl from Hahndorf. He fell out of favour with the Neuendettelsau and Immanuel Synod circles and left the mission in 1891. By 1908 he was at Buffalo in the USA.

A nephew born in 1884 in Sulzbach was also inspired by the letters from his uncle in New Guinea, and formed the aspiration early on to become a missionary. He attended the Neuendettelsau seminary from 1902 to 1906. Rev. Leonhard Flierl arrived in New Guinea in 1907 and stayed there with his wife Ottilie, who joined him in 1923, until 1929.[4]

To South Australia (1878)

| Rev. Johann Flierl with Johannes Pingilina at Bethesda |

.jpg) |

| Source: M00278, Lutheran Archives Australia |

The German Lutheran community in South Australia was now more than 40 years old, and Flierl found them well established, certainly no more backward than the Palatine villages he knew. A mood of revivalism has increased community support for missions and church, but the Lutherans had fractured into two synods, the Immanuel Synod maintaining connection with Neuendettelsau and supporting the Cooper Creek mission (established 1866), and the Australian Synod liaising with Hermannsburg and supporting the Hermannsburg mission (established 1877) .

The Dieri mission later known as Bethesda in the Cooper Creek area, had been set up in 1866 by two Neuendettelsau missionaries, Rev. Johann Friedrich Gößling and Rev. Ernst Homann, supported by the colonists Hermann Vogelsang and Ernst Jakob. It was shifted several times as seasonal lakes dried up and the Dieri adjusted their routes accordingly. Flierl arrived with the Meyers, who shared the mission house with the Vogelsangs. As so often, the laymen turned out to be more persistent than the ordained missionaries.

Flierl was the junior missionary here, accommodated in a single-room cottage and immersed himself into the study of the Dieri language, and prepared a universal reader (with Luther’s cathechism, bible stories, bible verses and hymns), even before the first church was completed in October 1880, at the Lake Killpalaninna site called Bethesda. At around that time he made his first journey back to Adelaide. The railway line was still under construction, so he had to walk 250 miles to catch the train at Beltana to Port Augusta, then the boat to Adelaide, where he arrived ‘looking like a hobo’, with no money, a swag and his toes poking through the boots, at the home of his financee. Later the rail reached Gums-Farina (130 miles) and by 1884 it reached Hergott Springs (70 miles from the mission – ‘Hergott’ meaning ‘the Lord’).

The missionaries had ignored the mission board’s reservations about moving back to Killalpaninna, ignored its instruction to commence wheat growing, and had sent Flierl south without permission. A four-member delegation now came for an inspection, and gave its belated consent for the already completed move to the old Hermannsburg station on Lake Killalpaninna. Flierl had constructed a three-bedroom cottage and obtained permission to return to Adelaide to get married in October 1882. His cousin Johann Flierl (II) was recruited as a replacement.

Setting up Hopevale (1886)

The Dutch had claimed the western part of the island of Papua in 1824. As German trading activities in the area increased, and rumours spread that the Germans planned to annexe the eastern part of the island New Guinea, Queensland annexed the southern part of the island in 1883. Britain refused to legitimise this move, and only when Germany annexed the northeast part of the island and Samoa in November 1884, Britain followed suit a few days later by establishing a protectorate in the southeast. The German ethnogapher and ornithologist Otto Finsch, after whom Finschhafen was named, visited New Guinea in 1884 and 1885, the boundaries between the British and the German areas were agreed in 1885, and in 1886 the German Neuguinea-Kompagnie was issued a trading monopoly and practically put in charge of the administration of the German territory (Kaiser-Wilhelmsland and Bismarck Archipelago).

The Lutherans responded quickly to the new developments. Flierl wrote to Neuendettelsau and the South Australian mission board which employed him requesting to be sent to New Guinea. He received immediate support from Neuendettelsau, which offered to organise finance from Germany. Flierl took his wife home to Tanunda and set off in November 1885, accompanied by Johann Biar from St. Kitts in South Australia.

In Sydney the German Consul General, who was an agent for the Neuguinea-Kompagnie, informed them that permission from company headquarters in Berlin was required, since the only transport to Finschhafen (from Cooktown) was undertaken by the company, who would only carry company officials and employees or specially authorised persons. Undaunted, Flierl appealed to Neuendettelsau and Adelaide for intercession, asked the consul general to become the business agent for the future mission, and proceeded to Cooktown, the new port servicing the Palmer River gold-rush (1873-83).

He settled in for a wait, and tried to make as many acquaintances as possible, including among the numerous Germans who had been attracted by the gold-rush, but who had no interest in forming a congregation. The first company ship to call from New Guinea - which actually got wrecked on Osprey Reef - had orders not to take Flierl on board under any circumstances. For Flierl this was not a setback but ‘a clear pointer from God’.[5]

The unhelpful attitude of the German trading company gave him a couple of months to spend at Cooktown, and he formed the idea that here was a good mission field. Flierl had very clear strategic objectives in mind, since Cooktown was the closest trading post to a future mission in New Guinea. It could be a stepping stone, and also serve as a half-way station and as a recuperation station for staff who needed a spell from the tropical climate. He found out that a large Aboriginal reserve had recently been set aside north of the town at Cape Bedford, about six hours’ walk away. He stepped right into an opportunity waiting to be taken up. The Queensland government promptly agreed to finance such a mission for one year, on the condition that it must be conducted for at least five years, must cultivate crops and seek to become self-supporting. Flierl agreed before inspecting the site. He also asked the Lutheran communities in the Logan area to support the mission.

He started to learn Koko Yimidir in Cooktown, and in January 1886 proceeded to Cape Bedford in a government boat loaded with government provisions, accompanied by Briar, Rev. Martin Doblies, an Aboriginal police officer, and a team of Aboriginal helpers. Police inspector Fitzgerald and the local magistrate Milman, also went for the trip and returned the same day,. He soon found that the reserve land was not suitable for white settlement, or for cultivation. The government also made available the Killarney sailing vessel, which was skippered by Brother Doblies who had maritime experience from his home in the Baltic Sea. They established Elim station with a coconut and maize plantation, although the maize produced little and the melons and pumpkin failed.

Within a few months of their arrival they were visited by the Governor, and it was announced that a second reserve had been set aside on the Bloomfield River, 45 miles south of Cooktown, which the Queensland government wanted to have run as a mission on the same terms.

Meanwhile the long-awaited consent of the Neuguinea-Kompagnie was obtained through lobbying from Neuendettelsau, and a replacement for Flierl was sent from Bethania. Rev. C. A. Meyer and his wife arrived in June 1886, accompanied by Johannes Pingilina. Biar, who was supposed to accompany Flierl to New Guinea, stayed at Hopevale for a short period and then went to New Guinea in private employment, whereas Doblies followed Flierl to New Guinea in 1887, however malaria forced him back to Queensland and he joined the Mari Yamba mission in 1887.

To Papua New Guinea (1886)

In July 1886 Flierl travelled to Finschhafen, the headquarters of the Neuguinea-Kompagnie, where he spent several weeks become acquainted with the newly forming colonial elite under the recently arrived governor Baron von Schleinitz with family including his father-in-law Baron von Hippel. The company officers had only been in the territory for a year: this was virgin land where Flierl’s enterprising spirit could develop to full fruition. His knowledge of Aboriginal languages was no advantage here. No prior work had been done on the local languages, except for a word list of about 100 Jabem words collected by the medical officer at Finschhafen Dr Schellong. Years later they realised that the word for ‘woman’ which they had been using actually only meant ‘tall’. It must have been obtained when someone pointed at a tall woman, asking what’s that, and the answer was ‘auwi palinggo’. Palinggo, instead of auwi was noted down as the word for woman.

After a few weeks Flierl was joined by Rev. Karl Tremel, and they recruited three assistants from George Brown’s Wesleyan Methodist mission in the Bismarck Archipelago (established 1875 with helpers form Fiji and Samoa). They selected a site at Simbang, less than two hours’ walking distance from Finschhafen. Some of the local villagers had themselves been displaced by the colonial occupation of Finschhafen. When they realized that the missionaries had come to stay rather than visit, they tried to drive them away.

| Simbang village |

|

| Source: Flierl 1910 |

Every morning we two missionaries alternated in school duties. We would go into the nearby village and attempt to coax children to our school. Or we would sit on the steps of our school and would try to persuade any children passing along the nearby track to come into the school, with more or less success. [6]

The school finally started when seven young boys presented themselves to make an agreement, that they would stay for seven months, attend school and work in the garden, much like they would sign on for a work contract. After the expiry of their term, they were relived by another group.

From here the mission took off and was eventually able to build outstations, as staff reinforcements arrived. In 1887 Rev. Doblies joined them for a few months, followed by Rev. Georg Bamler (who died in New Guinea in 1928). They established stations on both Tami Islands (1890) and at Deinzerhöhe (named after the Neuendettelsau director Deinzer). A malaria epidemic in Finschhafen in 1891 decimated the company staff and caused the German administration to move its headquarters to Madang in Astrolabe Bay, where the Rhenish Mission society (Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft, Barmen) had commenced its mission in 1887. This gave a strategic advantage to the Rhenish mission, and the Neuendettelsauers responded by establishing a site at Sattelberg as a health retreat, further claiming the Finschhafen area as their territory. In 1895 the Catholic Steyler mission society began a mission at Madang.

In 1899 the first baptisms were performed, after 13 years of work. That year the mission was reinforced with the arrival of Rev. Georg Pfalzer with his wife Mathilde (who both left in 1914), Sister Frieda Götz (who stayed until 1897), and Rev. Konrad Vetter (who died in New Guinea in 1906). Further stations were added in the Huon Gulf, with a supply station at Finschhafen (1903), a coconut plantation at Heldsbach (1904), and outstations Logaweng, Sialum and Wareo. At Heldsbach Flierl built his 12th house.

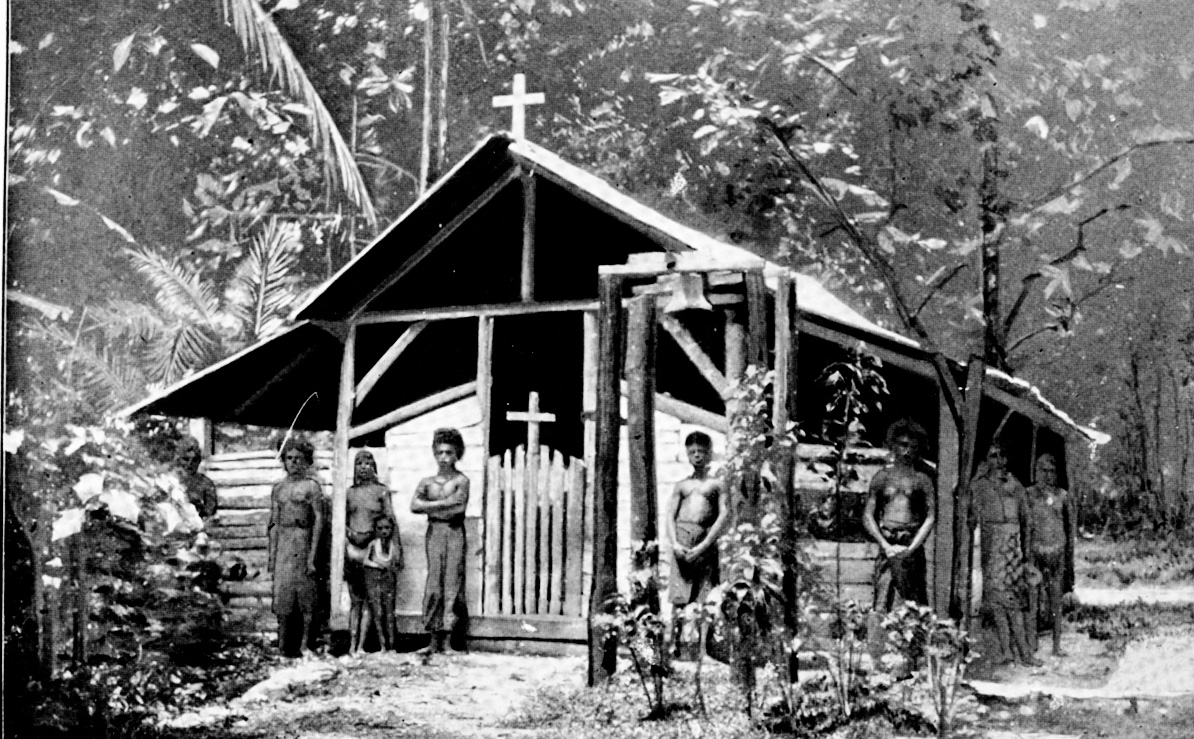

| First church at Tami Island |

|

| Source: Flierl 1910 |

Flierl’s four children were all born in New Guinea, and all remained firmly connected with missionary activity. Both his sons attended the Neuendettelsau seminary and returned as ordained missionaries. Dora became a mission nurse and teacher, remained unmarried, and looked after her father in old age. Elise married Rev. Dr. Georg Pilhofer, also a Neuendettelsau missionary in New Guinea.

As the Australians were taking command of the German territory in World War I, the German missionaries in New Guinea were required to swear an oath of neutrality. Flierl’s elder son Wilhelm was arrested in 1915 because two fleeing German officials took possession of his boat and left behind a box, so he was accused of assisting the enemy. He was interned at Liverpool (Australia), and repatriated to Germany at the end of the war. He then joined his brother Hans, who had been conscripted into military service on his arrival at Neuendettelsau in 1914, in Texas, and returned to New Guinea with his wife Maria in 1927, not having seen his family for 15 years.

World War I spelt the demise of the German colonial adventure and rendered the connections between Neuendettelsau and the Lutherans in America and Australia all the more important. The Australian Lutherans now took over the direction of the Neuendettelsau missions in New Guinea, and Australian-born Pastor Otto Theile, a Neuendettelsau graduate (1897-1901) became mission director in Brisbane. Under Australian rule the mission effort in New Guinea was reorganised and further extended, the Neuendettelsauers penetrating into the Central Highlands in the 1930s.

At age 72 Flierl left New Guinea for Tanunda, where his wife died in 1934, and in 1937 he returned to Neuendettelsau with Dora. The remainder of the family also returned to Germany under the gathering clouds of another war, only Wilhelm remained in New Guinea and was interned at Tatura (Australia) in 1940, together with other German missionaries including his brother-in-law Georg Pilhofer.

Flierl died on 30 September 1947, age 89. In 1972 Flierl Place in Canberra was named in his honour, the Louise Flierl Mission Museum at Hahndorf, opened in 1998, is named after his wife.[7]

Flierl was an imposing figure, tall, bearded, energetic and with a dry sense of humour. In the establishment of a mission field, he saw himself as ‘the pioneer, the forerunner’, leaving the role of teacher, language expert, and congregational leader to others.[8] His autobiography suggests that he was the driving force behind the mission extension in the Morobe district. Other accounts, however, lend far more weight to the pivotal role of ‘nationals’, local people without whom the white mission staff could not have succeeded.[9]

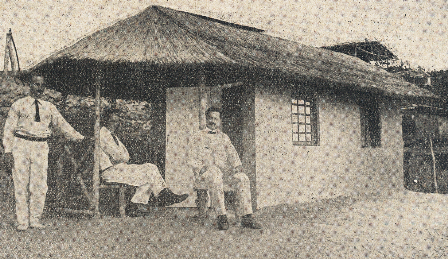

| German missionaries from New Guinea as prisoners of war in Australia |

|

|

'On the left stands missionary Willy Flierl, sitting under the roof is Missionary Raum, both currently pastors in the US, until they are allowed back to New Guinea. In the prisoner camp at Trial Bay in Australia they built this hut on the beach from posts, clay, timber boxes and reeds. Sitting on the right is Pastor Gutekunst, a German-Australian Pastor.'

Source: Koller 1924, p.121. |

[1] Flierl, Johann, My Life and God’s Mission, an autobiography by Senior Johann Flier, Pioneer missionary and field inspector in New Guinea, Lutheran Church of Australia, Adelaide, 1999, pp 9-33.

[2] Resume of Konrad Flierl, Neuendettelsau, Lebenslaufbuecher: Australien/USA, p.121.

[3] Resume of Johann Flierl, Neuendettelsau, Lebenslaufbuecher: Australien/USA, p.79.

[4] Resume of Leonhard Flierl, Neuendettelsau, Lebenslaufbuecher: Australien/USA; and Flierl, Johann, My Life and God’s Mission, an autobiography by Senior Johann Flier, Pioneer missionary and field inspector in New Guinea, Lutheran Church of Australia, Adelaide, 1999, p.253.

[5] Flierl, Johann, My Life and God’s Mission, an autobiography by Senior Johann Flier, Pioneer missionary and field inspector in New Guinea, Lutheran Church of Australia, Adelaide, 1999, p.112.

[6] Flierl, Johann, My Life and God’s Mission, an autobiography by Senior Johann Flier, Pioneer missionary and field inspector in New Guinea, Lutheran Church of Australia, Adelaide, 1999, p.138.

[7]Weiss, Peter, Short General and Statistical History of the Australian Lutheran Church, Lutheran Archives Australia, 2001-2007.

[8] Flierl, Johann, My Life and God’s Mission, an autobiography by Senior Johann Flier, Pioneer missionary and field inspector in New Guinea, Lutheran Church of Australia, Adelaide, 1999, p. 180.

[9]Wagner, Herwig and Hermann Reiner (eds) The Lutheran Church in Papua New Guinea: the first hundred years 1886-1986. Adelaide Lutheran Publishing House 1986.

Other sources:

Flierl, Johann, Dreiβig Jahre Missionsarbeit in Wüsten und Wildnissen, Verlag des Missionshauses Neuendettelsau, 1910.

Koller, Wilhelm, Die Missionsanstalt in Neuendettelsau, ihre Geschichte und das Leben in ihr. Neuendettelsau, Verlag des Missionshauses, 1924.