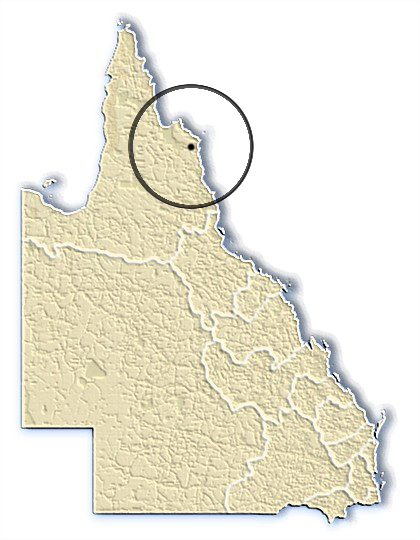

Cape Bedford Mission (Hope Vale) (1886-1942)

This was the first mission on Cape York Peninsula, and became the oldest surviving mission in north Queensland. It was initiated by Lutheran staff from Cooper Creek (South Australia) who established Elim and it became a stable community with the assignment of two young Neuendettelsau missionaries, Schwarz and Poland who stayed for 55 and 20 years respectively and added the Hope Valley site. The whole community was evacuated during World War II, because of its German missionary and lugger connections with Japanese. After the war Hope Vale was established on a new site. Outspoken and indomitable Missionary Schwarz is still remembered at Hope Vale which has remained a cohesive community and is home of a number of active and high profile indigenous activists.

A strategic stepping stone

The Guugu Yimidhirr of the Cooktown area were the first indigenous people who had extensive contact with James Cook and the Endeavour crew whom they taught the word ‘gangurru’ which has become adopted into all world languages. But it was not until the 1870s, with the discovery of gold on the Palmer River, that rapid white settlement affected the Guugu Yimdhirr. They came within the ambit of a government keen to regulate their activities, at the same time as German missionary initiatives were re-invigorated in the 1880s.

The Guugu Yimidhirr of the Cooktown area were the first indigenous people who had extensive contact with James Cook and the Endeavour crew whom they taught the word ‘gangurru’ which has become adopted into all world languages. But it was not until the 1870s, with the discovery of gold on the Palmer River, that rapid white settlement affected the Guugu Yimdhirr. They came within the ambit of a government keen to regulate their activities, at the same time as German missionary initiatives were re-invigorated in the 1880s.

In the 1880s Germany, unified under Chancellor Bismarck in 1871, became a colonial power in its own right, and acquired New Guinea in 1884. This changed the role and status of the German missionary training institutions, which were to play a central part in Germany’s colonial aspirations. The Neuendettelsau Mission Society authorised Rev. Johann Flierl from Cooper Creek in South Australia to commence a mission station in New Guinea. As had been the case in all other early colonial settings, the monopolistic colonial trading company nominally in charge of the territory, and seeking to maintain a free reign in its interactions with natives, resisted the encroachment of missionaries. When Flierl reached Cooktown in November 1885 to obtain a passage to New Guinea, his permission to enter the German territory was delayed, and he was stranded for a couple of months. He took this opportunity to establish a mission in this location.

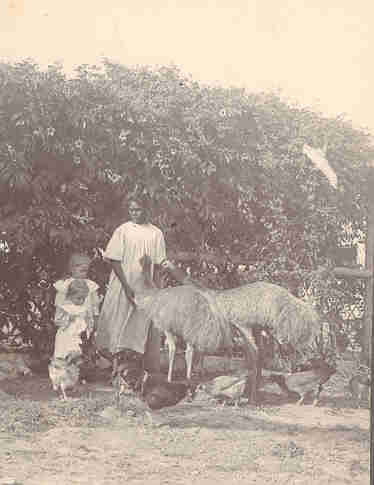

| Tame emus at the mission | Children at Cape Bedford |

|

|

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection | Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

For the Queensland government, it was a welcome receptacle for coastal Aboriginal labour then under much pressure from recruiters in the pearl-shell and bêche-de-mer industry, who were paid £4 per head of workers procured by whatever means, and from pastoral expansion. Pearl-shelling had commenced in 1868 in the Torres Strait and was expanding rapidly, and Cooktown was established in the wake of discovery of gold on the Palmer River in 1873, with a meteoric growth. Within a year it had 2,500 residents, eight hotels and its own newspaper, the Cooktown Herald. By 1876 a telegraph line and road to Maytown on the goldfields had been completed, and pastoral expansion uprooted Aboriginal people to such an extent that by the 1880s all the permanent waterways had been occupied rendering traditional Aboriginal economy unviable.[1] After an initial phase of ‘bringing them in’ to the town to perform odd jobs, the townspeople were by now insistent on exclusion of Aborigines from the town, where they were reduced to begging. In 1885 Aborigines were excluded from the town after dark. Police Magistrate Fitzgerald was frequently requested to arrest Aboriginal people who were merely camping on stations or near water sources. An unsupervised reserve had been set aside at the mouth of the Endeavour River, which was cancelled and removed further from town to Cape Bedford in 1881. When Flierl arrived, both the government resident at Cooktown, Milman, and the police magistrate were supportive of the idea of a mission, although they already knew that the reserve land was unsuitable for agriculture and ‘would never be self-supporting’.[2]

There was as yet no Aboriginal policy instrument other than the Native Police, so the Queensland government welcomed the assistance of the churches in the 1870s and 1880s. It was more than willing to declare Aboriginal reserves to facilitate settlement of arable land, and also maintained ration depots in the settled areas. The influential Moravian missionary Friedrich Hagenauer had visited North Queensland in 1885 and expressed the need to establish a mission there. (Negotiations over Bloomfield failed because Premier Griffith would only pledge support for the initial year, but six years later the Moravians established a mission at Mapoon.) An unequal bargain was hastily struck between the Queensland government pledging rations and other assistance for one year, and Flierl, undertaking to run a mission and school for five years, without having inspected the site.

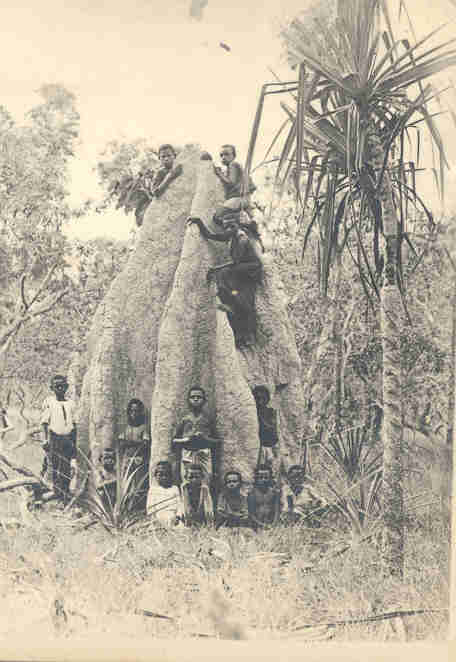

| 'People of Hope Valley' |

|

| Source: Flierl 1910 |

Mercurial commencement

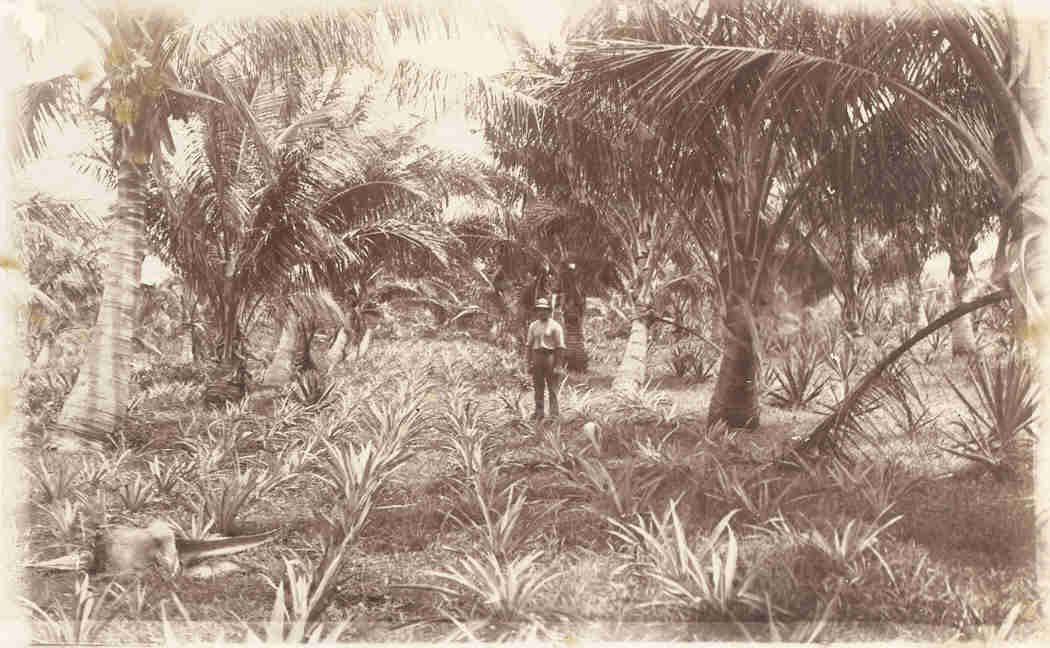

| Coconut plantation at Cape Bedford | Poland's house at Hope Valley |

|

|

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection | Source: Roennfeldt Collection, SLQ |

Coconuts became the staple crop of mission endeavour in the Pacific, PNG and tropical Australia. Coconut oil was used for cooking, but also as a softener in cosmetics and soaps, and transnational companies like Lever Brothers often supported the establishment of plantations.

Flierl himself stayed only half a year before departing for New Guinea, during which time he oversaw the planting of a coconut plantation – a condition of the government grant – and some less successful experiments with maize, melons and pumpkin at the coastal station they called Elim, where according to Exodus 15.27 the Israelites "camped there near the water" at an oasis of date palms.

Within a few months, the Governor visited the mission and told Flierl that a second reserve had been set aside on the Bloomfield River, 45 miles south of Cooktown in March, which the Queensland government wanted to have run as a mission on the same terms (which later became Wujal-Wujal).

Flierl obtained permission to travel to New Guinea and was replaced by Rev. C. A. Meyer and his wife Emma (nee Kaesler) who arrived from Bethesda mission in June 1886, accompanied by the Dieri evangelist Johannes Pingilina from Cooper Creek. The lay-helper Johann Biar, who was supposed to accompany Flierl to New Guinea, stayed at Elim for a short period and then went to New Guinea in private employment, whereas Doblies followed Flierl to New Guinea in 1887. Theo Knoll from Hamburg replaced Doblies as captain of the mission boat for a short period, but was dismissed, and replaced by the Jamaican Christopher Wallace.

In September 1886 Rev. Georg Pfalzer, a 20-year old Neuendettelsau graduate and his wife Mathilde arrived to assist Meyer. Pingilina facilitated their acquisition of Guugu Yimidhirr, and shared the school work with Pfalzer, teaching some 30 children in Guugu Yimidhirr.

In January 1887 Meyer, keenly aware that the one-year government grant was soon to run out (in April), started a rice plantation to demonstrate the sincere efforts to render the mission self-supporting. In March the mission boat was wrecked, the government refused to replace it, and the Fairy Queen was purchased for £120. Initially the boat seemed like a good source of savings and even a little income, undercutting the expensive rates of local fishermen, but by February 1889 the mission was unable to support the boat and it was sold.

In 1887, as government funding for Cape Bedford was withdrawn, the Immanuel Synod in South Australia, which had been seconding its mission staff to Cape Bedford, decided to take on nearby Bloomfield mission, leaving Cape Bedford entirely to the Neuendettelsau Mission society. Mission Inspector Deinzer in Neuendettelsau was not entirely happy with this arrangement. He referred to Bloomfield as the ‘fat cow’, getting liberal government funding, and Cape Bedford the ‘meagre cow’ to be financed by his society.[4] Consequently, the Meyers and Pingilina, who were from the Immanuel Synod moved to Bloomfield in May 1887, leaving Cape Bedford in the hands of the Neuendettelsau graduate Pfalzer.

Pfalzer, now with only Biar and the Jamaican Wallace by his side, felt slightly out of his depth. He wrote that their devotions presented a pitiful picture: “One of us can’t sing at all. The other cannot sing in German. And the third can only sing if someone leads!”[5] Pfalzer felt that the temptations of Cooktown were undermining the efforts of the mission, and went to attend a public meeting in town to argue that Aborigines should be barred from the town altogether - not only during night-time - so that they would not be able to take on odd jobs there. As he was being ferried around Indian Head by some Guugu Yimidhirr men, the canoe tipped over landing all his papers and speech and himself in the water. He came away from the incident with the suspicion that it had been no mere accident. He had a keen sense of the ironies inherent in his interactions with Aboriginal people. If his sermons went on for too long, he might get interrupted with the suggestion ‘do you want us to chop some wood, or dig the garden?’, or more bluntly, ‘are we getting something to eat now?’[6]

Late in 1887 the staff at the mission was again reorganised. Biar left for New Guinea, Captain Wallace brought his wife and child, so that Mrs Wallace assisted Mathilde with the kitchen and laundry, and in September the bachelor Rev Georg Schwarz arrived, with whom Pfalzer had shared a period at Neuendettelsau. Towards the end of the year Flierl came for a brief visit on his way from Simbang to South Australia. Pfalzer only remained at Elim for one and a half years altogether, until April 1889 when he and Mathilde, too, followed Flierl to New Guinea.

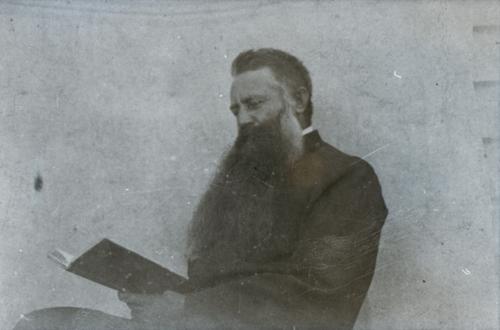

Stability: Schwarz (1887-1944) and Poland (1889 to 1909)

Schwarz was to stay for 55 years and make an indelible impression on this community. Like the Bavarian farm boy Flierl, he was pragmatic, driven by a sense of calling, and unstoppable. Soon the mission residents called him Muni (meaning ‘black’ in Guugu-Yimidhirr, like ‘schwarz’ in German), and those in the bush referred to him as ‘walarr’ after his flowing beard.[7] He is described as a ‘no-nonsense bachelor’[8] and the anniversary of his arrival is still celebrated at Cape Bedford on Muni Day each September.

| Missionaries Schwarz and Pfalzer | Pastor Poland | Rev. G. H. Schwarz (Muni) |

.jpg) |

|

|

| Source: Lutheran Archives Australia | Source: Lutheran Archives Australia | Source: State Libary of Queensland |

In June 1888 reinforcements arrived in the form of Rev. Wilhelm and Anna Poland who stayed for 20 years (1889 to 1909). Poland was an excellent support for Schwarz. These two gave the mission the stability it required for its success. Schwarz had wasted no time in declaring the soil at Elim to be unproductive and starting a second mission site at Hope Valley (Hoffnungstal), in December 1887. He had to give it up a few months later, but in April 1889, as soon as Pfalzer left for New Guinea and Schwarz himself took over the direction of the mission, he resumed the Hope Valley station again.

Poland was much more accommodating of Schwarz than Pfalzer had been. Much later their colleague at Bloomfield made a veiled reference to Schwarz’s autocratic style: ‘you know how Elim ended up because Schwarz managed for years as he pleased without even once consulting Poland’.[9]

For twelve years Poland and Schwarz conducted two mission sites, at Elim and at Hope Valley. Poland and his wife Anna ran the school at Elim conducting lessons in Guugu Yimidhirr, and Schwarz engaged in agriculture and cattle herding with the young men at Hope Valley. By 1893 the school enrolled 14 girls and 12 boys, and the mission direction in Neuendettelsau thought it was time to perform some baptisms. Only one baptism had been performed, the deathbed baptism in August 1892 of Delego, who was given the name of Marie. More girls were baptised in 1896 and 1897. Finally in 1899, after 13 years of mission work, the first adults were baptised.

Baptisms were an important performance indicator for missions. As Haviland points out, Flierl staked out seven goals for the mission[10], some of which were in tension with each other, and not all of which were equally important to all stake-holders. Baptism, as an indicator of Christianising, was clearly important for the mission societies. School attendance, as an indicator of civilising, was important for the government. Training in useful skills was important for the surrounding settlers.

The question of language

| Latin and Guugu-Yimidhirr inscription in the Hope Valley church |

.jpg) |

| This church was re-located to Spring Hill in 1939/40. Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Lutherans have always placed much emphasis on learning and using vernacular languages, holding strongly to the tenet that language is the mirror of a people’s soul. In all their mission fields they invested much energy into acquiring and recording local languages, in systematising their phonetics, and translating bible texts and hymns, always continuing Martin Luther’s project of translating the Bible (first published in German in 1534). Meyer brought with him Johannes Pingilina from the Dieri mission to facilitate language learning, and Schwarz later claimed that within three months of his arrival, he and Pingilina had translated the Lord’s Prayer into Guugu-Yimidhirr.[11]

Poland and Schwarz placed great emphasis on teaching in Guugu-Yimidhirr and soon some of the mission girls, including Maudie Mulgal, were engaged in teaching at the school. However, Police Magistrate Milman, who had been instrumental in initiating the mission with Flierl, visited in 1890 and insisted that the school must be conducted in English, as a condition on which a £200 annual subsidy would be paid. After all, if the mission was to fulfil a purpose for the settlers, the residents needed to be able to communicate in English in order to be employed. Government funding was stopped again in 1893 leaving Schwarz and Poland free to teach in what language they thought best, until the government agreed to fund a school at the mission and sent a paid school teacher, Mary Allen from Cooktown in June 1900. This settled the language question in favour of English. (By 1902 Mary’s sister Lucy Allen was also teaching at the mission.[12])

The missionaries prided themselves of letters written by their charges in Guugu-Yimidhirr, and would send these to Neuendettelsau where they would hopefully be circulated and published. One of these is a letter written in 1898 by a baptised girl who smashed a window in the girls’ dormitory in anger. Schwarz forced her to write an explanation to Neuendettelsau, which would have to pay for the repairs. Emma wrote a marvellous exercise in diplomacy (in approximate translation from German):

| Needle work class | |

|

Mrs Schwarz instructed the girls in needlework. Hand-sewn men's shirts and ladies clothing were exhibited at the 'Ekka', the Royal Agricultural Exhibition in Brisbane. Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Elim, December 1898

Mr Deinzer our friend,

I am writing to you without knowing you. You have brought us good tidings. We have very much enjoyed the girls’ dormitory which you granted us and we thank you for it. We do not wish to leave Elim at all, the land is beautiful here how God once made it. Coconuts and very nice sweet potatoes grow here and mangos and many fruits. Mr Poland grew them from seeds. We made a big garden. God also gave us enough fish in the water and meat. Maybe you will send us money for the girls’ house. I will not break the window of the house in anger again. I promise you. I want to drive the bad one away and be like a Christian.

Your friend

Emma

| In the original, with word-by-word translation | |

| Dauun antanun Mr. D | Friend our Mr D |

|

Ngayu nanu kapau degal ngarbalbego. Nundu antanun melbi botan merelin. |

I to-you letter send to-stranger. You to-us news good sent. |

| Antan Karbunmanati wurka bayen det churengga gura nanu thanks gural galmba. |

We were-happy very house you permitted and to-you thanks say also. |

| Antan Elim gaributongo dubinu yiebata boba botan | We Elim not-leave at-all here earth beautiful/good |

| God kanaigo balkai yiewaigo dirimante gura banggamu walubuton yandandal bera. | God once made here coconuts and sweet-potatoes beautiful grow. |

| Gura Mangos warkaigo mayidir unana. | And mangos fruit many are-here. |

| Mr. Polanda mokungai koparbi. Antan garden warka gurai. | Mr. Poland seeds planted. We garden worked big. |

| Mina puraiwe kutchungai Godugund antanun galmba kana umalma. | Meat, in-water fish God to-us also give enough. |

| Nundu antanun money bayenga deganu ngoba. | You to-us money for-house will-send maybe. |

| Ngayu kulingu kilada bayenga gari gura dumbinu. | I in-anger window of-house no-more will-break. |

| Ngayu nanu nila melbil. | I to-you now promise/tell/news. (Schwarz translates as ‘promise’.) |

| Ngayu warra ngarra tindanu gura walu Christian ningganu. | I the-bad-one will-chase away, and like Christian will-be. |

| Dauun nanu, Emma | Friend yours, Emma |

| One of the magnificent mango trees at Elim | Pineapple plantation |

|

|

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection | Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Emma, clearly angry with Schwarz, reserves her praise for Poland and Deinzer. At the same time she asserts that she will act ‘like a Christian’, rather than be the Christian which Schwarz wants her to be, and that she and the other girls want to remain at Elim, a place which was created for them in the beginning of time, into which they have mixed their labour, and which sustains them. Schwarz had a much more instrumental attitude to land.

The tussle with government

Schwarz was aiming at complete isolation of the mission residents from white settlement. He wanted to be able to offer work so that mission residents were not lured into town or to work on the luggers, where he said they gained not civilization, but ‘syphilisation’. Actually the mission was free from syphilis - a remarkable exception. Schwarz also refused to accept the ‘waifs and strays’ or offenders, work absconders or ‘morally destitute’ Aborigines which the government might want to allocate to the mission, arguing that it was not a reformatory. He refused to be recruited into government service through the money available to missions that were declared reformatories.

Government funding during this period was mainly dependent on the officials in Cooktown, and on their opinion on whether or not the mission served a government function. The government was not interested in Christianising Aborigines as a goal in itself, nor in preserving Aboriginal languages in order to understand ‘the soul of a people’. Neither was it interested in preserving a tribal homogeneity among Aborigines. All of these considerations were only subsidiary to the primary goal of ‘civilising’ in the sense of pacifying resistance, drawing people into a defined area of reserved land where they would not compete with expanding settlement, and teaching them skills with which they might be useful to settlers.

Henry M. Chester, the new police magistrate in Cooktown (1891-98) replacing Milman, did not share Schwarz’ vision. If missions were publicly funded then they ought to fulfil their role of training Aboriginal people for useful work with white employers. In a stand-off over Schwarz’s refusal to send mission girls to Cooktown to be employed as domestics, Chester suspended the annual government subsidy in 1893.

Government support continued to be purpose-tied. It had been withdrawn after the first year (1887), reinstated at the level of £200 around 1890 on condition that the school was taught in English, withdrawn again in 1893 over employment, reinstated again in 1898 in the form of rations, and in 1901 in the form of a publicly funded school, teaching in English. The shortfalls were made up from Neuendettelsau which carried the funding of the mission for several years, sometimes to the tune of up to £600 per year.[13]

In the 1890s the Australian colonies underwent a profound depression triggered by bank crashes in London and Melbourne, real estate speculation in Victoria, and falling wool prices due to oversupply. Falling foreign investment caused a credit squeeze and unemployment peaked at 30%. By the end of the decade the unions had flexed their muscles and failed, and formed political parties, and the colonies were considering the interests which they had in common. There was much talk about what the future of Australia was to look like, and the question of race loomed large in these debates. Governments took a renewed interest in the management of Aboriginal and other non-white populations, and Cape Bedford received a succession of official visitors.

Archibald Meston toured the northern missions as ‘Special Commissioner of Police’ and was greatly impressed with Schwarz’s mission. Schwarz accompanied him from Hope Valley to Bloomfield, with which Meston was much less impressed, finding it overfunded with a government salary of £300. (That salary had only been paid for one year, in 1886.) Meston calculated that less than £18,000 had been spent on Queensland Aborigines since 1882.[14]

In late 1897 the Neuendettelsau mission committee asked Johann Flierl to re-visit and write a report about Cape Bedford. The committee carried the mission over its funding shortfalls but felt that it was not being kept well informed. Flierl claims that his subsequent lobbying in Brisbane achieved the reinstatement of government funding.[15]

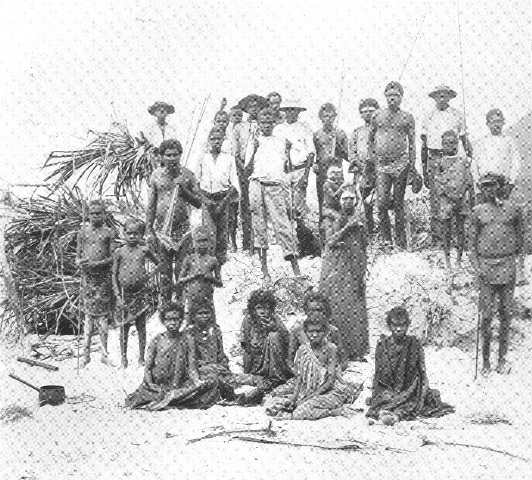

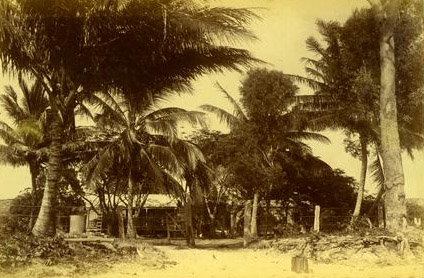

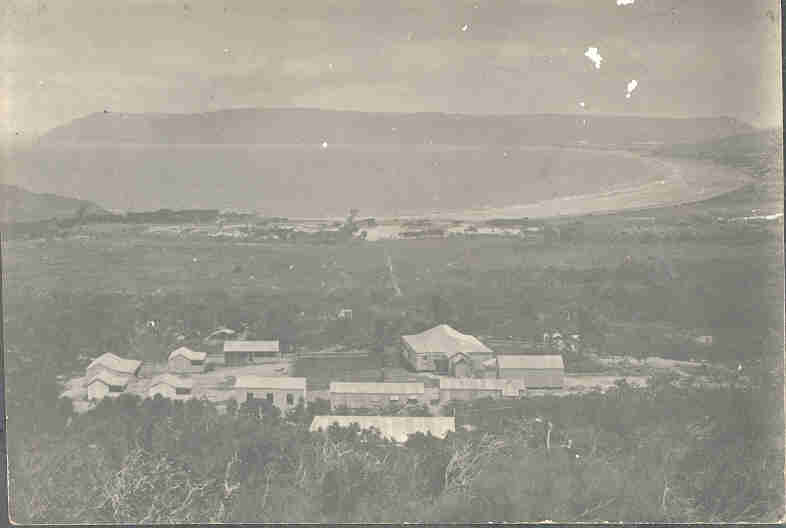

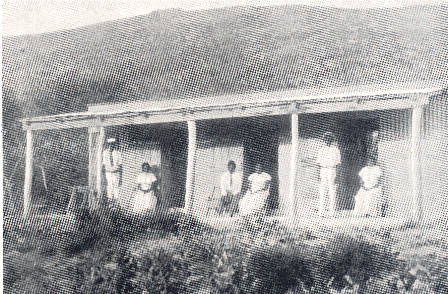

| Hope Valley mission station in 1899 | View of Hope Valley |

|

|

| Source: J.G. Foxton collection, SLQ | Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

However, Schwarz orchestrated his own impressive intervention when the newly appointed Northern Protector of Aborigines, Dr. Walter Roth, was in Cooktown in 1898. Schwarz walked with 25 men from Cape Bedford to Cooktown to present the case for the mission. (They could have easily taken a boat instead.) Roth was clearly impressed and paid a visit in ‘spring’ (probably April) 1898. In late 1898 William Parry-Okeden, the Police Commissioner in charge of Aboriginal affairs followed up with a ‘flying visit’. The appointment of Roth under the supervision of Parry-Okeden was a result of a comprehensive Aboriginal protection act passed in 1897. Roth was a medical doctor and ethnographer, and inquired whether the four marriages planned by Schwarz for young mission residents were ‘proper’ according to tribal customs. He was impressed with the absence of syphilis on the mission, and praised the efforts and results of the missionaries. Minister of State J.F.G. Foxton also visited in 1899, and he, too, gained a favourable impression.

Consolidation

On 8 and 9 March 1899 the mission was damaged by the massive cyclone which also destroyed north Queensland’s pearling fleet. Several buildings were unroofed and the mission boat damaged, and again Schwarz, with a keen eye on public relations effects, got one of the mission girls, Magdalene Mulun, to write to Parry-Okeden to request a new boat.[16]

In 1900 Schwarz decided to close down Elim and consolidate at Hope Valley. The mission girls at Elim strongly resisted the move to Hope Valley, they did not want to go there.[17] But the government had approved funding for a school at Hope Valley, so that this was going to be the focus of Schwarz’s mission rather than attempting to employ adults in agriculture. The new school teacher, Mary Allen from Cooktown, arrived in June 1900, and by February she was engaged to Schwarz whom she married on 21 May 1901.

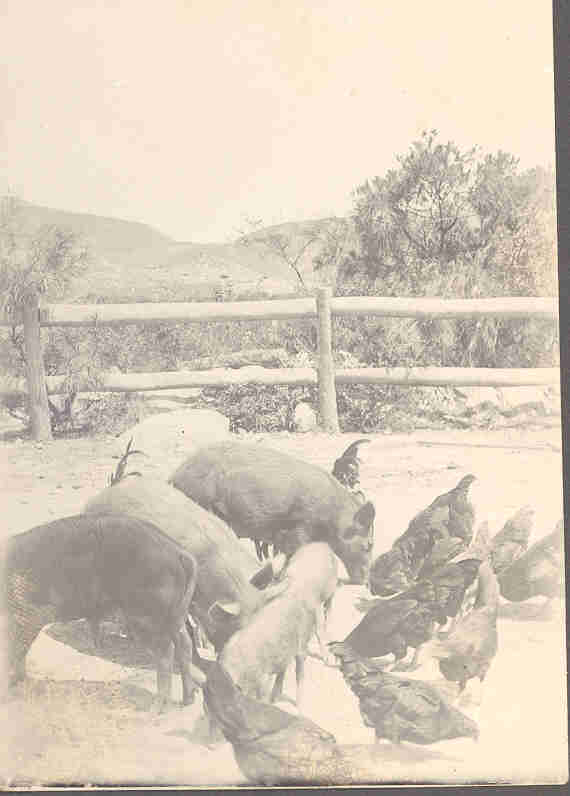

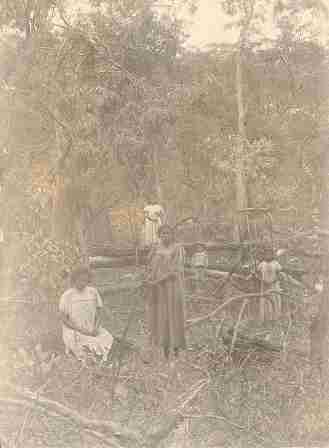

| Farmyard | Women clearing the scrub |

|

|

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection | Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

There was also another development recommending this consolidation. Both missions at Mari Yamba and Bloomfield were collapsing. Mari Yamba was without an ordained missionary since March 1898, and from the middle of 1900 the Immanuel Synod considered ist retreat from Bloomfield. By September 1901 Schwarz had decided to take on Bloomfield, to the amazment of ist former missionary Hörlein, who wrote to his mission director ‚You must have been surprised that Schwarz took over Bloomfield. I nearly went back there.’[21] The Polands were stationed at Bloomfield for half a year to oversee the winding down of the mission. In February 1902 Schwarz also agreed to accept the Mari Yamba residents if the Queensland synod was willing to pledge financial support in return.[22] In July 1902 Freiboth arrived in Cooktown with 24 people from Mari Yamba, but Schwarz requested that Freiboth take seven of them to Bloomfield, where he was to disassemble one of the houses for relocation to Hope Valley. Presumably there was no Aboriginal labour whatsover left at Bloomfield. Poland brought the remainder to Hope Valley soon after. As a result of this consolidation Hope Valley now received a £50 annual contribution from the United German and Scandinavian Lutheran Synod of Queensland, and a contribution from the Hermannsburg mission society in Germany.[23]

By now the facilities on the Hope Valley site were a big mission house, two dormitories, one for boys one for girls, a stable and some smaller buildings. In 1903 the church at Hope Valley was consecrated and twelve mission residents baptised on the occasion, including six girls and one boy under ten, and five young men.

Several patches of swampland had been drained to plant potatoes and pineapples interspersed with coconuts.

Schwarz maintained a ‘no work – no food’ regime and therefore did not want the mission to become a government ration depot. The mission residents were highly regimented and their lives followed a strict rhythm dictated by the bell.

A typical day at Hope Valley is described by Poland[24]:

6.00 the bell rings to rise, the women go to bathe at the waterhole, the males go to the dam

6.30 bell for church service and roll-call, followed by sweet tea and bread

7.30 the bell rings to get ready for school

8.00 school bell

12.00 dinner bell

5.00 bell for religious instruction

6.00 bell for evening service

9.00 bedtime bell

A number of support staff entered and left the mission besides Schwarz and Poland. Walter Roth observed during his visit that a Swiss gardener, ‘old Fritz’, provided fruit and vegetables and every few months a bullock or pig was killed for meat. In 1911 Hermann Wiedemann (born 1889) arrived from Neuendettelsau where he had only spent a year. He left the mission in 1912 and arrived back in Germany in 1913.[25]

Still under pressure to render the mission self-supporting, Schwarz attempted to grow copra and sisal fibres commercially in 1902. At Elim the coconut plantation started by Flierl with 300 seedlings was expanded to 1,300 trees, and with a special government grant and donations from Lutheran communities, ninety acres were planted with sisal. But when the fibre was sent for sale in Sydney it was judged to be of non-commercial quality. (Some sisal was still there around 1923, near the hospital, where Roger Hart rememberd it as a child.[26])

| Muni showing the sisal crop |

.jpg) |

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

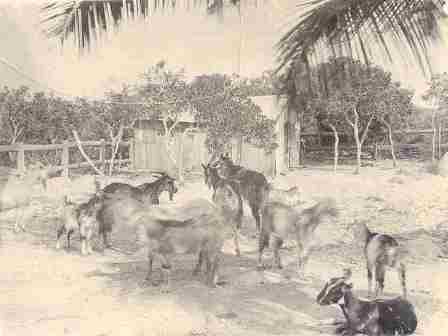

Harvest festival at the mission,

|

Harvesting coconuts and pineapple |

Goat herd |

.jpg) |

|

|

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection | Source: Maria Schwarz collection | Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Undefeated, Schwarz lobbied for the extension of the mission reserve to include the McIvor River, where he established Wayarego outstation. Here a number of indigenous families including Deeral, Pearson, King, Baru, Gibson, McLean, and some Bridge Creek people, worked their own garden plots with sweet potatoes, bananas and hundreds of coconut palms. The plan was to settle newly baptised couples, and to grow cotton for export. For a few years the Rev. Fritz Medingdorfer, who arrived from Germany 1927, supervised this outstation, but he departed again in 1932. The mission reserve was again extended in 1934, to include the Mt Webb area, and Wayarego outstation was closed in 1936, when its soil was exhausted.

The pattern was as always good initial returns and then a decline, because the fertile patches of land simply did not stand up to intensive agriculture. Poland complained about the unreliable rainfall:

German farmers should count themselves fortunate to be living in a land in which rain, that magnificent gift of God, pours down upon them regularly and abundantly, year by year. [27]

The Polands went on furlough in 1905, and during their absence the mission was hit by a cyclone in 1907 (see Schwarz entry). They only returned briefly and left Cape Bedford in 1909.

The following were recorded as mission residents by Pastor Poland in 1908 and 1909[28]:

Married couples with their children:

'Baptized girls at Hope Valley'

.bmp)

Anna and Frieda at rear, Elizabeth, Maria, Delego, Martha

and Magdalena in the centre, Alice, Dirkan, Darobol at front (no date).

Source: Poland 1988, p.53.

William Daku

Elisabeth Tulo ] Johannes

Henry Baru

Martha Muru ] Freddy and Willie

Jakobus Nimamarkatelie

Mirjiam Balare ] Karl and Hans

Bertie Wayi

Emma Yirbil ] Bertha, Didi, Filia

Karl Wannbirdigame

Luise Dakargo

Andrew Dinemo

Helene Mulgal ] Frank, Eva, Lea

Arhur Barni

Tabea Ngurkul ] Barney, Millie (girl)

Phillip Mamatchi

Anna Kakural ] Arhur, Alekku

Martin Rattler

Frieda Nimagodaigo ] Dan

Leonhard Bondoltchi

Lydia Manira ] Meta

Joseph Dirnggulu

Maria Delego ] James (29 07 08), Matena, Filius

Unmarried men and youths:

Daron (from Mari Yamba)

George (from Mari Yamba)

Otto – Gonchowolo

Girls:

Magdalena Mulun

Clara Wauudatai (from Bloomfield) (later George Rosendale’s grandmother)

Ruth Dudur

Greta Darobul

Lina Dirkan (died July 1910)

Alice

Dora

Hanna Yirbil (died Pentecost 1909)

Winnie (from Mari Yamba)

Lily

Mandie (mixed race)

Elsie Nunaimale

Hilda (died February 1911)

Minni

Bertha (Ngamu Dingal) (died 1908)

| 'The first three Christian married couples' |

|

|

William and Elizabeth, Jakobus and Miriam, Henry and Martha (no date). Source: Poland, 1988, p. 56. |

Total number of living christians (1908): 50

Of which 11 married with 12 children

1 unmarried man

2 youths

13 girls

Baptised at Pentecost 1908:

Bunggari – from Mari Yamba, over 30, unmarried

Demtihi Charley under 30 years

Georgie over 20

Albert under 20

Mapin under 17

Darken under 15

Patty under 13

Topsie – Bessie over 20

Annie under 20

All 12 families of which 1 mixed descent, 18 children, 2 bachelors, 7 youths, 15 girls = 65

Baptised in 1908:

Billy (Ngambibogo)

Nelly (Mulgal) (couple)

Yital male youth ca. 20 years

Butihan male youth ca. 20 years

Doburitin 12-15 years

Woibo 12-15

Yurin 12-15

Bedford 12-15

Ca. 30 pupils

Friction with neighbours

The cattle herd, numbering 400 head in 1894, shrank to about 90 head by 1902, due to neglect and cattle duffing from neighbouring pastoralists who tended to claim any cleanskins, until Peter Byrne was engaged as stockman around 1911. George Bowen, one of the Mari Yamba people, told a story of how while they were fencing at the McIvor River in 1914, one of the neighbours accused them of spearing a calf at Mt Webb. He appeared with a policemen, found his path blocked by the new fence and tore it down. The workers repaired it, and he tore it down again on his way back. Schwarz achieved the dismissal of the constable and a fine of £50 to the station owner.[29] This defensive move of fencing and cattle tending fanned friction with neighbours, which came to a head during World War I.

| Outstation homes for married couples |

|

The photo is annotated 'Spring Hill homes', but the SLQ collection shows Source: Roennfeldt collection, SLQ. |

World War I interrupted communications with Germany, so that Schwarz took it upon himself to make major decisions without consultation. He had never been a friend of sea transport and beach locations, and moved the whole mission to Spring Hill at the southern end of the reserve, where a road now connected to Cooktown. His wife had ongoing medical issues and spent much time in Cooktown. In 1915 a farm at Eight-Mile, just outside the southern end of the mission reserve, was offered for sale, and Schwarz negotiated to rent it for five years. He also purchased Fuller’s Crossing, halfway between Eight-Mile and Spring Hill, in his wife’s name, and stocked it with 38 head of cattle purchased from her funds with the intention of reimbursing her when communications with Germany could be resumed. This led to an invective letter from the Cameron brothers, who had taken over a neighbouring property in 1910, to MLA Ryan, alleging that this ‘officially pampered Hun’ was running private cattle on rent free government land with Aboriginal labour. The entire mission, in Cameron’s opinion, should be placed ‘under a Britisher’:

the consensus of local opinion is that the alien is receiving much greater consideration than has ever been extended to other settlers in the district. …. With the universal polish of the educated Hun, the Bedford Missioner Schwarz is accomplished in covering his confidentially expressed sentiments (an intense hatred of the British and everything British), but the external veneer seems hardly sufficient to warrant subsidising an institution conducted by an enemy subject to teach the Aboriginals German sentiment and German language.[30]

Between the wars

| The Spring Hill church |

|

|

|

This building was taken apart and relocated to Spring Hill, Source: Roennfeldt Collection, SLQ |

World War II and its aftermath

| Father Schwarz |

|

| Source: State Library of Queensland |

_thumb.gif)