The Hessian farm boy Georg Schwarz became one of the most prominent missionaries in Queensland. During his 55 years at Cape Bedford Schwarz threatened several times to leave, keenly aware that his purpose was not always aligned with that of the government. Although naturalised he was interned during World War II and completely severed his links to Germany. He died in Cooktown at age 91 and was interred at Hope Vale, where he was known as Muni and is still remembered there with annual celebrations of Muni Day.

Early life

|

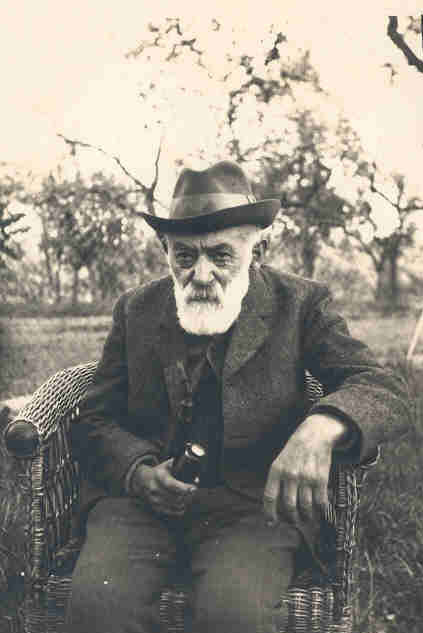

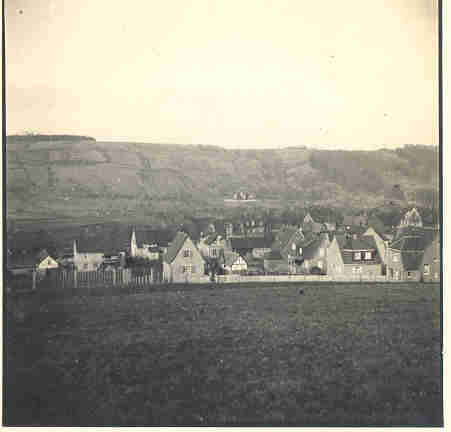

The Schwarz family home at Altenstadt (Höchst)

Source: Maria Schwarz collection

|

|

St. Martin's church at Altenstadt

|

In this church Georg Schwarz was ordained in 1887. The family has remained closely connected to its independent Lutheran free-church background. Munil's great-grand nephew Andreas Schwarz was also ordained here in 1985. In 1978 Pastor George Rosendale from Hopevale held a sermon here. The church was heritage listed in 1982. |

Georg Heinrich Schwarz was born on 31 January 1868 at Höchst near Frankfurt. He was the sixth of nine children of Johann Heinrich Schwarz (1858-1932) and Maria Katharina Kempf (1964-1937).

Theirs was a Lutheran family, who joined a Lutheran free church when their local priest was expelled from the unified Protestant state church in 1874 for nonconformist ‘old-Lutheran’ principles. At age 15 he entered the Lutheran mission school in

Neuendettelsau, in Bavaria.

When he received his ‘call’ to Australia, a special examination was set for him in 1887 in order to graduate him from the college in time, answering questions in dogma and ethics, to replace Father Pfalzer at Elim (Cape Bedford).

Schwarz was ordained at the St Martin’s church in Höchst (Altenstadt) on July 10th 1887, then spent some weeks in England to master the English language, and travelled in company with Georg Bamler who was destined for New Guinea. He arrived at Cape Bedford in September 1887. He was young, inexperienced, pious, determined, and driven by a strong sense of calling.

On leaving Neuendettelsau college at age 19 Schwarz was required to write a resumé:

Resumé of Georg Heinrich Schwarz

Born at Höchst on the Nidder, county Büdingen in the grand duchy of Hesse on 13 January 1868, I spent the time to my 15th year, that is until my entry into this institution, in the parental home. When I was age eight my parents and whole family left the state church together with our priest. At that time I did not yet comprehend this step, but gradually I became aware of its validity and even necessity. Because Reverend Bingmann was not permitted to remain in Höchst, I received my religious education from the priest in the state church. Only after I completed school was I able to commence catechismal classes with Reverend Bingmann. From late April 1883 until October I received four hours instruction almost daily, except Saturdays, and in October I was confirmed. I had long harboured the wish to enter into missionary service. I became acquainted with this institution through Reverend Bingmann, and it was through his mediation that I arrived here as an Aspirant at Easter 1883. After four years I have finally reached the goal of my aspirations. In the week from Exodus to Pentecost I have sat for my examinations alone and on the afternoon of the first Pentecostal day I was consecrated together with Bamler. If God wills we will commence our journey to Australia (Elim) in July. May the Lord provide me with the courage, strength and constancy to perform my arduous profession as a missionary to the heathens.

31 March 1887, Neuendettelsau[1]

Nineteen-year-old Schwarz left behind his parents, seven siblings, and a niece with whom he maintained a regular correspondence, trying to communicate the victories and success of his efforts through photos. (These photos were donated to the State Library of Queensland by Maria Schwarz and Elfriede Paul nee Schwarz in 2007.) He was never to see his German family again.

Schwarz was from a rural area, and knew about working the soil. Where he came from, women and men worked together in the fields, children were expected to help with agricultural work, and parents and teachers used corporal punishment to assert their authority. The German seasons dictated forward planning and good timing and the hoarding and preservation of food over the winter. The houses nestled together in small villages leaving the surrounding area for agriculture, much of which was conducted co-operatively. This background imprinted itself on Schwarz’s strategies at CapeBedford, where he sought to approximate this model.

Arrival at Cape Bedford

When Schwarz arrived at Elim in September 1887 he joined Georg and Mathilde Pfalzer, assisted by the Jamaican Wallace and his wife.

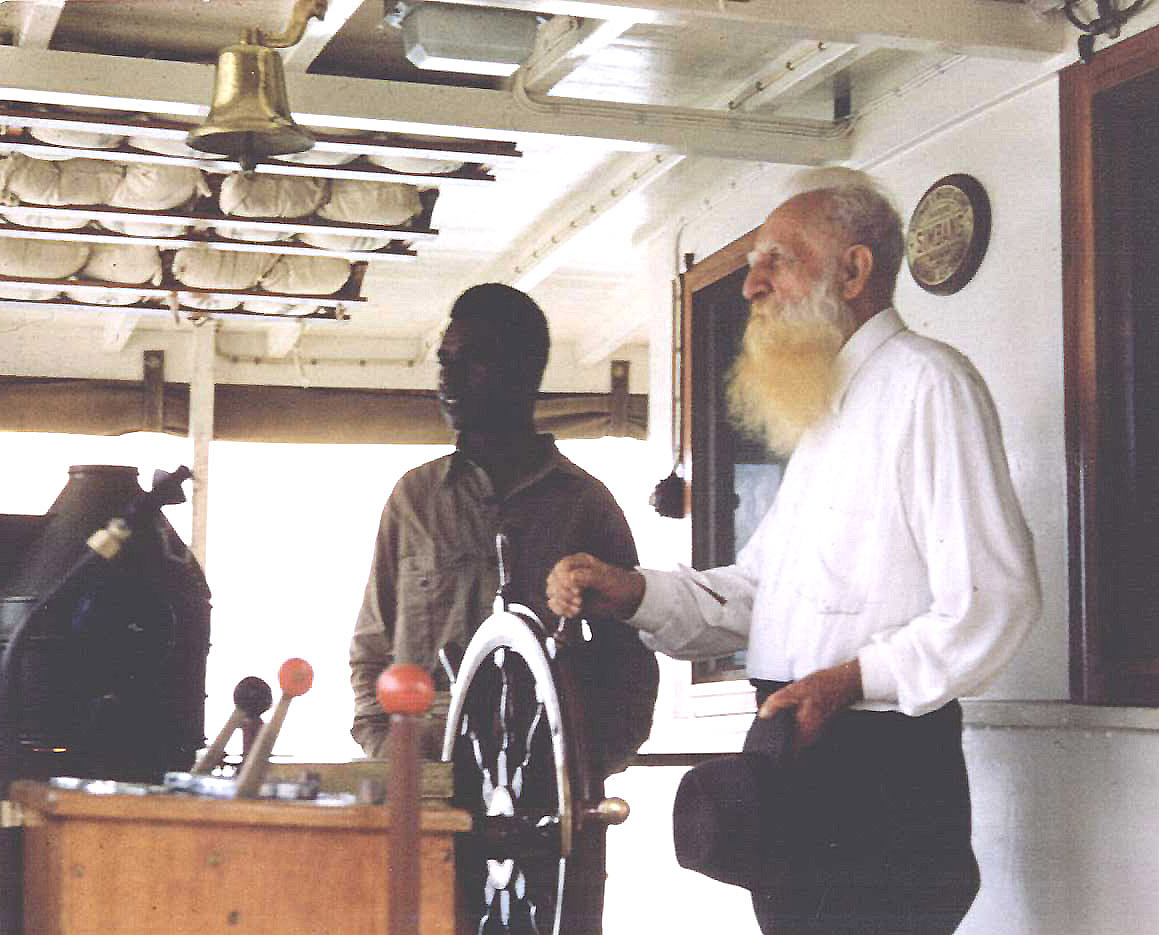

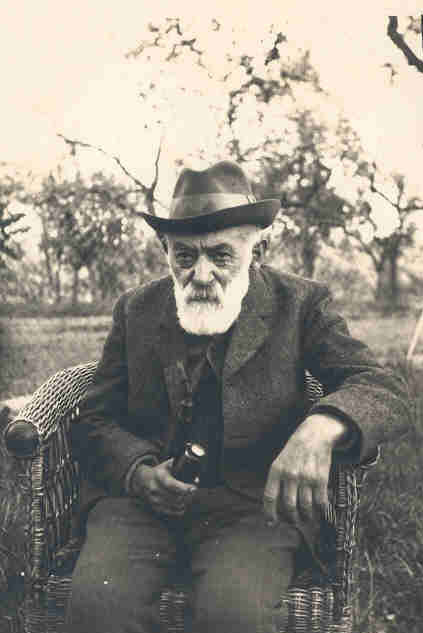

| Father Schwarz, or Muni |

Muni's brother, Karl |

Muni's mother |

.jpg) |

|

|

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

There was some mutual sizing up between the young Schwarz and the Guugu-Yimidhirr. Like all newcomers to Cooktown, Schwarz had been initiated into the local folklore about cannibalistic natives, and the Guugu-Yimidhirr men played on the respect which this reputation earned them, never denying the rumours. On one occasion they reputedly marked out on Schwarz’s back the sections of human flesh they themselves had eaten, which ran shivers through his spine (presumably they tried to explain the meaning of ‘kidney fat’). On another occasion one of them is said to have told Schwarz that since he was so ‘good’, he must be good to eat, too.

[2] Such stories, taken at face value and reported to the Lutheran communities which supported such missions, added interest and adventure to the reports of the toiling missionaries.

Schwarz tried at first to teach the proper pronunciation of his name to the Guugu-Yimidhirr, but ‘all that comes out is

wux’.

[3] When he explained that it meant ‘black’, they settled for ‘muni’, the Guugu-Yimidhirr word for ‘black’, and this was to become his local name, although those not on the mission referred to him as ‘walarr’ (beard)

[4] a reference to the flowing beard which he felt lent him some respect. His travel companion Georg Bamler observed that when they arrived together in the north, Schwarz appeared to be uneasy with the local natives, who looked fierce.

[5]

Because of his long presence on the mission, stories about Schwarz have become layered with myth. For example, when Schwarz first arrived at Cooktown, he and Bamler unexpectedly arrived two days early at Cooktown, so that there was nobody to meet them. One version of the story of his arrival is that with typical initiative, he hired a boat to take him to Cape Bedford, but was accidentally dropped at a beach just short of the Cape, and spent the night in a cave at the place which was later to become HopeValley. Pfalzer, on the other hand wrote a few days after Schwarz’s arrival, that when he came to pick up Schwarz and Bamler from Cooktown he found that they had checked into the most expensive hotel in town.

[6] Muni Day at Hope Vale is celebrated on 13 September to commemorate the night spent in the cave.

Another story remembered about Schwarz is that with Johannes Pingilina’s help, he translated the Lord’s Prayer into Guugu-Yimidhirr within three months of his arrival at Elim.

[7] Linguist John Haviland, the foremost expert on this language area, has not been able to find this translation. He also concluded from the translations that are extant, that Schwarz was ‘not a natural linguist’, never fully comprehending the subtleties and grammar of Guugu-Yimidhirr and, by imposing some German grammatical forms, practically created a language, which was subsequently taught to all who arrived at the mission from elsewhere. Indeed, every first bible translation into a strictly oral language created a formalized language.

[8]

Entrenching the mission

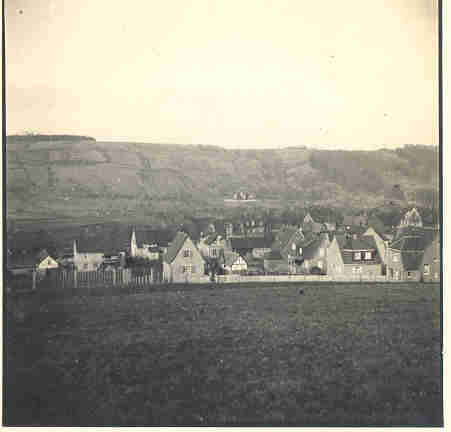

| The village of Altenstadt |

Agricultural village life at Altenstadt (Höchst) |

Tending the fields, Altenstadt |

|

|

|

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Schwarz had no predilection for the sea, either as a means of transport or as a source of sustenance, and found the beach location of the first mission site at Elim to be highly disadvantageous. No sooner had he arrived in September, than Schwarz founded a second mission site, Hope Valley in December 1887, because the soil at Elim was clearly unproductive. But by May 1888 they resolved to abandon the site again.

In June 1888 reinforcements arrived in the form of Wilhelm and Anna

Poland. Poland had shared at least one year at Neuendettelsau with Schwarz, and during his twenty-year residence at the mission formed a lifelong friendship with him. He visited Schwarz’s family in Höchst twice, the last time in 1934 or 1936.

[9]

A year after the Polands’ arrival, in April 1889, Georg and Mathilde Pfalzer left for New Guinea. Schwarz, now in charge, immediately revitalised the Hope Valley outstation and convinced

Neuendettelsau to fund a gardener’s wage for one year to engage a Mr Nutt in setting up a plantation. While they were maintaining two separate mission stations, the Polands conducted the school at Elim with about 26 children, while Schwarz engaged the young men in agriculture and cattle herding at HopeValley.

Schwarz’s situation as a missionary bachelor was unusual, but clearly he had little opportunity to remedy it. In 1893 now age 25, he was planning to marry Poland’s sister-in-law Mrs Beisel who had meanwhile joined the mission staff. He had been on a £20 salary for his first six years, and asked Neuendettelsau for an increase to £50. (The superintendent at Bloomfield had been appointed at a government salary of £300).

Schwarz reported, in one of his rare but long letters, that the £200 government subsidy was now uncertain, and that in order to maintain the two stations at Elim and Hope Valley, which could easily employ 50 of the 100 adults now at the mission, Neuendettelsau ought to commit itself to funding at the level of £450 per year. Otherwise, he wrote, it might be better to give up the two stations, or put someone else in charge. It was not the last time he threatened to walk away. He felt that his mission was being disadvantaged (‘stiefmütterlich behandelt’) relative to Flierl’s New Guinea mission. (These two competed for space in the

Kirchliche Mitteilungen, the Lutheran monthly newsletter ‘Church News from and about North America, Australia and New Guinea’.) His long letter ends with the news that not the £50 as expected, but £118 had just arrived from Neuendettelsau, and, instead of re-writing the whole letter, Schwarz merely asked the committee in the final paragraph to ignore what he had just said about being neglected. ‘I can barely write five lines without being called away for this or that.’

[10]

The Neuendettelsau committee continued to send money, but found the reports from Schwarz inadequate. When Johann

Flierl, the founder of the mission, went on his first furlough from New Guinea in late 1897, Mission Inspector Deinzer in Neuendettelsau asked him to inspect Elim and Hope Valley ‘which requested more and more subsidies without keeping the authorities back home informed.’ Flierl recollects:

The situation at Hope Vale was somewhat unusual: The two missionaries Schwarz and Poland, while getting on with each other reasonably well, were entirely different natures. Schwarz, the senior missionary, was of an independent nature and a good worker, but did not see the need for reporting to the mission authorities back home. The station was never self-sufficient and continued to be a financial burden to the church. However, his spiritual work bore fruit: He established a church and school and the small congregation continued to grow. …… Before departing, I had tried to impress on Missionary Schwarz the necessity of keeping the home authorities fully informed of all aspects of the mission work at all times. During the war, I received a letter from Missionary Schwarz, the only one I ever received from him.

[11]

Whether as a result of Flierl’s lobbying, or as a result of Schwarz’ impressive and theatrical march to Cooktown with 25 men from Cape Bedford to Cooktown to see the new Northern Protector, in June 1900 the government agreed to fund a school at the mission and to pay a school teacher.

New responsibilities

| The Schwarz family |

The Schwarz family |

Father Schwarz with Grace and Mary |

|

|

.jpg) |

| Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

Source: Maria Schwarz collection |

The new school teacher was to turn Schwarz’s life around. A year after her arrival, Mary Allen, the daughter of the Cooktown postmaster, married Schwarz on 31 May 1901. The new couple’s plans for a honeymoon in Germany were foiled by the news that Bloomfield was to be closed down and its residents assigned to Hope Valley. One year later the Mari Yamba mission was also closed down and its residents brought to Cape Bedford.

The arrival of the Mari Yamba people prized open Schwarz’s ethnic enclave at Cape Bedford, after some 15 years of dealing only with Guugu-Yimidhirr. He had always defended the mission from forced assignments of residents, arguing that it was not a reformatory, and had resisted pressure to place mission girls into paid employment outside of the mission. Schwarz strenuously objected when the new residents organised a cricket match against a Cooktown team. The temptations of civilisation - or ‘syphilisation’, as he called it - were his major enemy. He threatened that anyone who left for the cricket match was leaving the mission for good. Most of the Mari Yamba people took him by his word and left the mission.

Schwarz’s first daughter Grace (later Behrendorff) was born in November 1903, and his second daughter Marie (later Bennett) three years later. These two were not allowed to speak any language other than English, just as their mother taught only in English, with the result that the mission girls were noted for their fine command of the Queen’s English. Surrounded by his Australian family, and with the question of the mission language settled by government funding requirements, Schwarz gradually distanced himself from his German background.

In 1907, while the Polands were on furlough in Germany, the mission was almost entirely flattened by a severe cyclone. Mary Schwarz related her experience of the terrible event to Anna Poland, and Muni translated her letter for publication alongside his own report in the mission newsletter.

Letter from Mrs Schwarz to Mrs Poland, 3 February 1907

(explanations in brackets were inserted by Schwarz)

… at around 3.30pm the roof of our house flew away. When we saw that it was too dangerous to remain any longer, I took the children and carried them to your house. Heinrich (Father Schwarz) stayed behind and took some clothes and linen from the commode and cupboard and sent everything in small boxes to your place, also the beds, mattresses and blankets, then covered our piano and when he himself came up around 6pm he said the church was still standing. We hoped it would survive, but in vain. Next morning it was gone. ….

None of us had any dinner. I only gave some bread and biscuits with milk to my little ones and the black kids. At 8pm the storm was at ist worst. Your verandah was torn off as well as the iron panels on the roof, and the wall of your living room where the regulator hangs started to tremble. We had to leave the house in great haste in pitch dark night under the deafening sound of the iron sheets tearing off and beams crashing. Most of us lost the blankets that were still dry when we fell into the swollen creek behind your house, and those that were wet were too heavy to carry. The storm ripped the singlet from my husband’s body. We both lost our shoes. I got holes in my stockings and my hair was completely disshevelled. But we thanked God for saving our lives. … Never have I so longed for daylight as in that night. We got about 12 inches of rain. When we returned to the station in the morning on the path strewn with torn trees, beams and iron sheets, we considered it a miracle that none of us was killed or seriously injured. Only William (one of the Christians) had a cut in his leg. …. We now had a lot of wet and spoilt clothes. It took about a week before everything was dry again, because it kept raining. I have been wearing some of the clothes which you sent us for Christmas for the black girls, and couldn’t get a dry shoe for more than three days.

The furniture in your house didn’t suffer too much. Your mattresses were wet but have dried out again. Heinrich is already at it to repair everything that can be fixed, and is very busy during daytime, and writing letters at night. Last night I slept in our house again for the first time. Our poor Grace (4 years) was so frightened when she saw all the houses destroyed that she still cries whenever she hears wind and sees rain, and she asks me anxiously whether we’ll get another storm. – After the cyclone a lot of dead chickens were lying around, and goats, we found a dead horse and several dead cats. – Our boat had a big hole. The sails were torn and the mast broken. We will have a lot of expenses. – The roof of my mother’s house in Cooktown was blown away. The storerooms of merchant Clunn have been completely destroyed. He is one of those who suffered the most damage.

It is now 11pm and I have to end. Mr Field will carry the letter to Cooktown tomorrow. Today I held school again for the first time since the storm, on our verandah, where Heinrich also holds the church services because we don’t have a church any more. I also want to tell you that our boys, girls and married people conducted themselves laudably during this terrible time.

All Hope Valley people send their regards to you, your husband and children.

I remain your sincere friend,

Mary Schwarz

Schwarz’s report on the night of the cyclone:

The Polands’ house appeared to best resist the cyclone, and I took my wife and children there. All Hope Vale residents gathered there around us. … From there we saw and heard how one house after the other crashed and flew away in pieces. The floor of the boys’ house for example flew off in one piece (30 x 12 ft), and crashed 150 yards away on a rock; the entire wall of the schoolhouse (30 x 9ft) including windows and doors came flying over the fence into our garden; a heavy iron-clad chest flew from the storeroom to our house and hit the wall of my study, and so on. …. At around 9pm on Saturday the verandah (of Poland’s residence) broke into pieces, the iron flew away, the beams crashed into the windows and the remaining roof, and soon the whole house started to bend and creak. Expecting its complete collapse at any moment, we had no choice but to leave this last refuge, but where to go? I decided to try and reach the blacks’ camp about a half mile away in a sheltered spot with my wife and children, we couldn’t remain in the house any longer. Placing ourselves in the care of the Almighty, we took our children, my dear wife took the little Marie (one year old), and I took Grace (4 years old), threw blankets around them and entered into the night in God’s name.

Outside pitch black, streaming rain and the irresistible force of the terrible cyclone. We barely took a few steps from the house that the storm grabbed us. My wife and little Marie were thrown to the ground, I attempted with all might to stay upright, but was thrown into the crown of an uprooted tree after a few steps. My dear wife could impossibly keep upright by herself, much less carry and protect the child. Mr Field took little Marie, and no sooner had he grabbed her that the storm ripped him away from us, and we saw neither him nor the child until about an hour later when we were reunited at the camp. A strong black man held and supported my wife. We too only stayed together for a short while, lost each other in the dark, couldn’t hear each other call even when we were close together. ….. We reached the camp bleeding and half naked, but all alive. ….. The old Aboriginal woman at whose place we found shelter, straight away procured an unused woolen blanket from a bag and gave it to my wife to wrap little Marie, and one of the school girls had managed to bring a dry dress all the way to the camp, in which she dressed Gracie although her own teeth rattled with cold ….Next morning …. we stood with our children in streaming rain on the ruins of Hope Valley. …..The damage will barely be covered by £500.[12]

Another debacle arrived with the ethnic tensions brought to a head by World War I. By this time the mission had incurred the wrath of neighbours by starting to fence and tend its cattle with an overseer in 1911. Cut off from communication with Germany Schwarz made some financial decisions without consultation, and purchased some property in his (Australian) wife’s name. In 1916 he was accused by a neighbour of being an ‘educated Hun’, an ‘enemy subject’ who had an ‘intense hatred of the British and everything British’, and was teaching the Cape Bedford people ‘German sentiment and German language’. Not even the most flattering part of these allegations, that he was ‘educated’, has any ring of truth in it. Schwarz had been naturalised and had therefore given up his German citizenship. He was 48 and had spent almost thirty years as a missionary in the north, it was all he knew, the foundation of his identity.

| Modernity catches up with the mission |

|

Tommy McDonald, Cairns jeweller and pioneer aviator,

sometimes undertook mercy flights with his

Dragon Rapide single-engine biplane, here landed

at the mission beach with Schwarz posing.

Source: Maria Schwarz |

Anti-German sentiment was so strong during World War I that many townships and families anglicized their names, and the mission’s financial support and organisational direction from Neuendettelsau finally came to an end. Responsibilities were devolved to second generation German immigrants whose experience of religious persecution was less direct. Brisbane Lutherans set up a mission board and obtained some funding from the Iowa synod.

Schwarz was forever lobbying for the extension of the mission reserve. In 1919 he (again) threatened to resign if it was not extended.[13] He continually looked for new pastures, new patches to plant, new means of generating an income. Not only was there a financial imperative, he really wanted the mission to be self-supporting, so that he could employ Aborigines at the mission instead of watching them sign on with exploitative employers. He also wanted the mission to be a haven of the remnant tribes in the area (Haviland 1998:94), and therefore long refused to accept Aboriginal children of mixed descent.[14] He was well aware that other communities that were compliant with government purposes, were better off financially. The much smaller Yarrabah reserve, he observed, had a steamer, a printing press, a power saw, gas lights, a reliable water supply and the phone connected when Cape Bedford was struggling along with a £250 subsidy.[15]

Schwarz finally went on furlough in 1922, but not to Germany. On his return he found the mission in a financial crisis, and again drew on his private means to make mission purchases.

[16] The Lutheran donations had fallen to a low ebb, and the mission board in Brisbane was negotiating for a take-over by the Australian Board of Missions. Schwarz dug in his heels to prevent the mission from becoming Anglican. If this came to pass, he threatened ‘we and most of our people intend to leave Cape Bedford’

[17]

He managed to marshal continued support, and an assistant missionary, F. Medingdorfer arrived from Germany in 1928 to supervise the Wayarego outstation, where baptised couples had been settled on their own plots on the German village model. Medingdorfer left again in 1932, the mission was again extended, to include Mt Webb, and Wayarego outstation was closed in 1936. Later that year lay-helper Victor Behrendorff arrived from South Australia and soon married Schwarz’s oldest daughter Grace, and their son Ian was born at Spring Hill in October 1938. Marie married a dairy farmer from Eumundi.

Withdrawal

| The backyard at Altenstadt today |

|

This is the house in which Muni was born. It was right at the main street of Altenstadt in typical farmhouse design for a rural village. The kitchens were usually at the back of the house leading to a courtyard, bordered by sheds, workshops and stables in which a goat or cow might be kept for milk, a chicken pen, an outhouse and septic tank, and a kitchen garden. Maria Schwarz and Elfriede Paul show the backyard of the renovated Schwarz family home in 2007, with a new residence on the left, and the old main house on the right having been bricked in and upper storeys added. |

World War II spelled the end of Schwarz’s missionary life. He had completely severed his links with his German family, had long been naturalised, and had spent considerable energies in preventing interactions between Japanese recruiters and the Aboriginal people under his care. Still, suspicions about ‘enemy aliens’ quickly resurfaced. Even before the civilians in the north were advised to evacuate in March 1942, Schwarz sent his wife, daughter Grace Behrendorff and grandson Ian down south on 12 February. In April Schwarz’s car was confiscated by military authorities making it difficult to travel. On 11 May the director of the mission board Otto Theile learned from the Department of Native Affairs that the entire mission was to be evacuated, and the American army trucks rolled in on 17 May 1942. Some of the mission residents suspected that Muni had known of the evacuation.

At age 74 Schwarz was interned in Brisbane for four months. He was arrested at 8-Mile, arrived at the camp on 22 May and in August he was released into the custody of his daughter Marie Bennett at Eumundi. He was sometimes able to catch up with some of the CapeBedford people who had been allocated to arrowroot picking at Beenleigh, where Poland was holding services. His unconditional release came in June 1944, whereupon he visited his former ‘flock’ at Woorabinda.

Now age 76, he moved with his wife to Cooktown into a lowset cottage in Charlotte Street. At his internment he was required to disclose all his assets which amounted to less than £300 plus two cottages in Cooktown, one of which was furnished. He owned a Radiola valued at £50, a 1939 Chevrolet valued at £300, £50 in war bonds, and he was paying back several loans.

[18]

A new mission site was set up at Hope Vale in 1949, and gradually the Cape Bedford people were finding their way back. The community was now supervised by Pastor V. Wenke, and each time some of his former charges returned, Schwarz greeted them at the Cooktown wharf.

Schwarz remained hostile to the policy of assimilation and watched from a distance how his life-work appeared to get undone. He needed coaxing and cajoling to deliver the occasional sermon to replace an absent pastor at Hope Vale.

[19] But a number of loyal supporters kept visiting him in Cooktown where they would tend his garden and chop his firewood, and they built a cyclone shelter to his specifications in his backyard.

[20]

Schwarz died in Cooktown on 22 March 1959 and his body was laid to rest in the centre of the Hope Vale cemetery. His German family learned of his death from the Concordia Lutheran newsletter.

When he left Neuendettelsau as a 19-year old, Schwarz had prayed for courage, strength and constancy. He certainly displayed these attributes in his long working life. Despite all the cultural differences he brought to Cape Bedford, he is fondly remembered there. In 1973 the Schwarz Memorial Hospital was dedicated at Hope Vale, and Muni Day is annually celebrated on 13 September to commemorate his arrival.

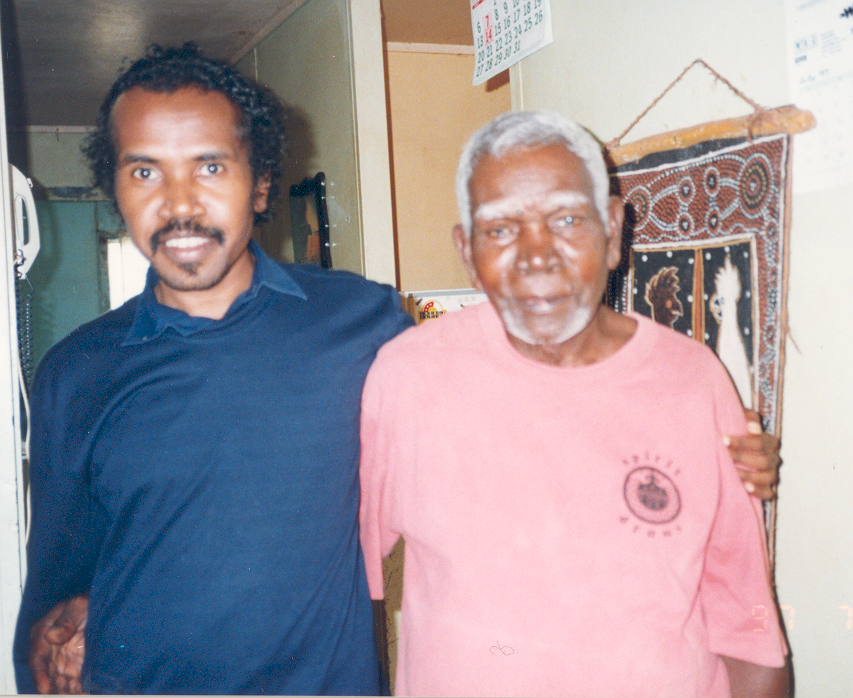

In July 1978 Hope Vale residents Peter Costello and Pastor George Rosendale visited Germany and called at Höchst to make contact with Muni’s family. Costello later said it was one of the highlights of his European tour to see Muni’s hometown. They also visited the Neuendettelsau archives, Heidelberg, and Muni’s grandson at Oberursel. Hope Vale continued to receive some support from the Lutheran mission society in Vienna, whose Professor Walter Schlesinger facilitated the European tour of the two.

[1] Translated by R. Ganter. The grand duchy of Hesse enforced a union of Lutheran and reformed churches in 1874, to which 114 pastors objected, among them pastor Kar Friedrich Bingmann, who was stripped of his office and forced to leave Höchst. His congregation remained supportive of him and continued to define themselves as an ‚evangelical-Lutheran congregation’. In 1878 religious congregations were allowed to be formed outside of the state church (Landeskirche), and in 1885 St Martin’s church was consecrated as a free church, with Bingmann ceremoniously re-instated as ist pastor. The parish is still a member of SELK (Selbständige Evangelisch-Lutherische Kirche in Deutschland – independent protestant Lutheran Church in Germany) and has about 130 baptised members. www.selk-hoechst-usenborn.de/

[2] Pohlner, Howard J. Gangurru, Adelaide, Lutheran Church of Australia, 1986, p. 43; Rose, Gordon, ‘The Heart of a Man: a biography of missionary G.H. Schwarz’, Yearbook of the Lutheran Church of Australia, 1978, p. 48.

[3] Kirchliche Mitteilungen 12, 1887:92.

[4] Haviland, John with Roger Hart, Old Man Fog and the last Aborigines of Barrow Point, Bathurst, Crawford House Publishing 1998, p. 89.

[5] Pohlner, Howard J. Gangurru, Adelaide, Lutheran Church of Australia, 1986, p. 43.

[6] Pfalzer letter to Deinzer, 20. 9. 1887, cited in Pohlner, Howard J. Gangurru, Adelaide, Lutheran Church of Australia, 1986, p. 40.

[7] Haviland, John ‘How much food will there be in heaven?’ Aboriginal History vol. 4, December 1980, Part 2, p. 133.

[9] Maria Schwarz, pers. comm. 2007.

[10] Schwarz to Neuendettelsau, 21 August 1893 MA 42/2. Reprinted in Traungott Farnbacher and Christian Weber (eds) Ein Zentrum fuer Weltmission – Neuendettelsau – Einführung, Zeittafeln, Dokumente, Namen 1842-2002. Neuendettelsau: Missonswerk der Evangelisch-Lutherischen Kirche in Bayern, 2002.

[11] Flierl, Johann, My Life and God’s Mission, an autobiography by Senior Johann Flier, Pioneer missionary and field inspector in New Guinea, Lutheran Church of Australia, Adelaide, 1999, p.164.

Pilhofer, Georg, Die Geschichte der Neuendettelsauer Mission in Neuguinea, Freimund-Verlag, Neuendettelsau, Vol 1, 1961, p. 164

[12] Kirchliche Mitteilungen, 17 April 1907 No4/5, pp35-38.

[13] Haviland, John with Roger Hart, Old Man Fog and the last Aborigines of Barrow Point, Bathurst, Crawford House Publishing 1998, p. 99

[14] Haviland, John with Roger Hart, Old Man Fog and the last Aborigines of Barrow Point, Bathurst, Crawford House Publishing 1998, p. 94

[15] Pohlner, Howard J. Gangurru, Adelaide, Lutheran Church of Australia, 1986, p. 66.

[16] Rose, Gordon, ‘The Heart of a Man: a biography of missionary G.H. Schwarz’, Yearbook of the Lutheran Church of Australia, 1978, p. 57.

[17] Schwarz to Theile, 29 September 1924 in Rose, Gordon, ‘The Heart of a Man: a biography of missionary G.H. Schwarz’, Yearbook of the Lutheran Church of Australia, 1978, p. 58.

[18] Schwarz, Report on Prisoner of War, National Archives Australia Series MP1104/2, control symbol Q490, available online after log-in.

[19] Rose, Gordon, ‘The Heart of a Man: a biography of missionary G.H. Schwarz’, Yearbook of the Lutheran Church of Australia, 1978, p. 62.

[20] Ian Behrendorff, pers.comm. April 2009.

.jpg)

.jpg)