Mapoon (1891-1919)

More than fifty years after the Zion Hill missionaries tried to emulate the ‘Moravian model’, the first Moravian mission in Queensland was established at Mapoon. Its success was largely due to the 28-year staying power of its first missionary, Nikolaus Hey, who implemented distinctly Moravian regimes and seeded a string of missions along the east coast of Cape York Peninsula.

Seeding the idea for North Queensland mission

Shortly after the first Moravian mission in Australia at Lake Boga was overtaken by a gold rush and abandoned in 1856, the Moravians made a second attempt in Victoria, working with Presbyterian assistance. Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Spieseke completed his missionary training in London and returned with Friedrich August Hagenauer in 1858 to establish Ebenezer mission in the Wimmera. They added a second mission called Ramahyuk in Gippsland in 1863 (closed in 1908). These were model villages with firm routines, dormitories, and zero tolerance for indigenous customs.

Shortly after the first Moravian mission in Australia at Lake Boga was overtaken by a gold rush and abandoned in 1856, the Moravians made a second attempt in Victoria, working with Presbyterian assistance. Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Spieseke completed his missionary training in London and returned with Friedrich August Hagenauer in 1858 to establish Ebenezer mission in the Wimmera. They added a second mission called Ramahyuk in Gippsland in 1863 (closed in 1908). These were model villages with firm routines, dormitories, and zero tolerance for indigenous customs.

The success of Ramahyuk so enhanced Hagenauer’s reputation that he was appointed Protector of Aborigines in Victoria. In this capacity he was able to make strategic recommendations which colonial governments would take seriously. He implemented the Victorian Aborigines Protection Act 1886 which evicted people of mixed descent from the supervised communities, and therefore tore many Aboriginal families apart. Biological family played a subordinate part in the Moravian pietist community.

On a northern tour in 1885 Hagenauer proposed the urgent need to set up missions in north Queensland, where the large-scale introduction of South Pacific Islanders raised humanitarian concerns. A number of initiatives (such as Bridgman’s at Mackay) had already sought to train Aboriginal people as a substitute labour force for plantations. He felt that missions could step into this role, fulfilling both political and economic objectives.[1] The Victorian alliance of Moravians and Presbyterians stepped back from this idea when it became clear that the Queensland government was unwilling to commit funding for more than one year, but the lacuna was filled by Lutherans establishing missions at Cape Bedford, Mari Yamba and Bloomfield in 1886 and 1887.

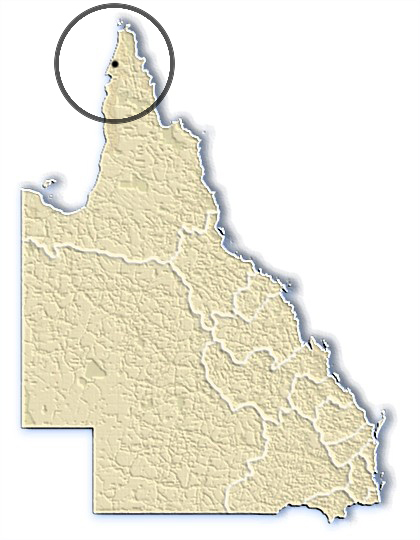

Meanwhile the 1886 Presbyterian Federal Assembly had already committed itself to setting up a northern mission, and Presbyterian community committees had been set up in Victoria to collect funds and support the mission idea. Something had to be done. In 1890 Hagenauer with Professor Rentoul and Professor Henry Drummond, again entered into high-level negotiations. At Thursday Island the government resident John Douglas was strongly supportive.[2] Douglas was battling against abuses of Aboriginal labour by recruiters in the beche-de-mer fishery and wanted supervised recruiting stations along the coast of Cape York to regulate and monitor this industry. He suggested a location on the western side of Cape York which had become the most recent recruiting frontier. In 1890 the Victorians sent a delegation of Messrs. Hardie and Robertson north to consult with Douglas. Together they inspected the site near Cullen Point at Port Musgrave and a 100 square mile reserve was declared at Mapoon (meaning sand-hill).

The Arrival of the Moravians

Two Moravian missionaries were designated to undertake this task, John G. Ward, son of a Jamaican missionary, educated in Germany and England[3], and the German Nikolaus Johann Hey. Hey received his call to North Queensland in 1890, but completed his missionary training at Herrnhut, and was then sent to Ireland to meet Ward and improve his English. He was ordained in May 1891, and introduced to his future wife Mary-Anne Barnes, the sister of Mrs. Ward.

|

Rev. John and Matilda Ward, and Rev. Nikolaus and Mary-Anne Hey |

| Source: Lutheran Archives Australia |

The Wards and Hey left England in June 1891 destined for Melbourne to meet Hagenauer. They arrived at Thursday Island in November. John Douglas welcomed them, and Aboriginal Protector Bennett and Police Inspector Brett assured them of support. Douglas remained supportive until his death in 1904.

On 27 November 1891 a small fleet surrounding the government steamer Albatross delivered a 13-strong party to the mission site. Douglas himself came along for the journey. Ward and Hey came with police protection and Aboriginal workers, two builders and building materials and provisions.[4] They took four days to unload everything, and then Douglas and Ward returned to Thursday Island, leaving Hey at the mission.

Hey’s letters give the impression that he was landed in a threatening wilderness. ‘The carpenters slept on board, we slept on shore with loaded guns. The blacks were howling all night.’ Rumour had it that just months before their arrival ‘the local tribe killed and ate two white men’.[5] But Ward’s brother Arthur, writing The Miracle of Mapoon (1908) reveals that the people who greeted them at Mapoon wore shirts and spoke English, because they had already had much contact with luggers. Being used to paid work, they adapted quickly to the ‘no work – no food’ principle’ imposed at the mission.

They started clearing and building, erected a chicken pen, and Hey kept visiting the Aboriginal camp to befriend them with gifts. Once the mission house had been completed the building party returned to Thursday Island. By this time Hey had started to train a young local boy, claiming to have ‘found a little boy who didn’t have any parents, and since he didn’t have a name yet I called him Willie. I made him a pair of pants. He is useful to me, he fetches my water and does other little services’.[6]

After four weeks the Wards arrived and the following year Hey brought his new wife to the mission. The two couples settled into the mission and regularly reported to Hagenauer as president of the Melbourne Presbyterian mission committee, and to the Moravian mission direction at Herrnhut which continued to cast an eye over the staff it sent into missions. Soon they had a small bush church and extensive gardens.[7]

Most of the useful land on the Cape was already under pastoral lease, on which Aborigines were shot on sight. They therefore were on a constant war path with the stations by killing cattle and horses. To address this problem, a neighbouring settler, Mr Embley of Batavia Downs, donated a small herd of cattle to the mission, and this became the beginning of a cattle industry at the mission.

The missionaries started a school and Sunday services, tended to the sick and injured, and reported progress when by the end of 1892 one of the boys called Mrs. Ward ‘mother’.[8] By 1893 they had between 20 and 40 children at the school learning to read and write, and the children were taught English hymns, like ‘Jesus loves me’. The number of willing workers fluctuated from 15 to up to 60. They were paid in food.

Four years after their arrival, on 3 January 1895 Rev Ward succumbed to fever. Hey and the two women took sick leave for several months, leaving the station in charge of Charles Hodges. When they returned ‘only a few Aborigines were left to greet us’, clothed in rags and covered in sores. The buildings had suffered from the rains, and after the raining season malaria and influenza spread, affecting almost 100 of the locals. Hodges, too, had been sick with fever most of the time. Hey was not satisfied with Hodges who was not a Christian ‘but at least he hasn’t exerted a bad influence yet’.[9] Soon the local people started coming back to help with the reconstruction of the mission station.

| The new church at Mapoon |

.jpg) |

| Source: Lutheran Archives Australia |

It now became incumbent on Hey to lead the mission, which he did until 1919. Ward’s widow, who had been appointed to the mission in her own right, not merely as a dependent wife, remained on the mission until 1917.

In 1896 a new church at Mapoon was consecrated in Ward’s honour as the Ward Memorial Church, on which occasion the first converts were baptised in the name of Jimmy and his wife Sarah and their two-year old son Victor, along with Hey’s daughter Ina and the daughter of mission assistant Charles Hodges.In that year the Moravian brother Edwin Brown and his wife joined the Mapoon staff. It had always been Douglas’s plan to establish a string of missions along the coast, and two years after Brown’s arrival, he was placed in charge of new station at Weipa along the same model as Mapoon, with dormitories, married quarters, and some industrial activity.

Regulating Mapoon

Hey acquired the local language, and his ‘elementary grammar of the Nggerikudi language’ was published as North Queensland Ethnography Bulletin No. 6 in 1903 edited by Walter Roth. In retrospect Hey admitted some amusing setbacks in their attempts to acquire the local language. For a long time they used the word ‘tarraka’ to mean ‘heart’, because this was a body metaphor used by the Wik Mungkan for ‘wickedness of the human heart’. On one occasion when they were dissecting a fowl and naming the various organs, they realized that ‘tarraka’ was the liver. Hey explained the mistake to those present, and they had a good laugh at the expense of the missionaries. Other difficulties arose, of course, from the impossibility of translating terms into a language where they do not exist, such as ‘resurrection’.[10] Hey also observed that the local language did not contain a term for ‘punishing’ or ‘disciplining’. The closest terms were ‘revenge’ or ‘fight’. He discovered this in 1909, when the mission was under public scrutiny for an incident of physical punishment (see below).[11]

Despite their engagement with the language, the missionaries struggled to understand indigenous customs and views. They often intervened in traditional paybacks, and Ward’s Miracle of Mapoon contains an image of Matilda Ward as ‘missionary heroine’ throwing herself into a fight.[12] Only a few months after their arrival Hey described how Bamptrin’s sister left her husband Charlie for a man called Captain Cook. To compensate for the loss Bamptrin demanded Cook’s sister, but she refused to leave her husband. Bamptrin then speared his sister. The spear was lodged in her neck and almost killed her, being difficult to extract because it had a barb. She ran off into the bush and fainted, nursed by her new husband. Hey and several women went to pick up her up and carry her to the mission house where Sister Ward nursed her back to health within a few days.[13]

Hey waged a war against polygamy. He saw it as giving rise to much trouble, but more importantly, an enemy of Christianity, indeed the work of the devil, notwithstanding that the Old Testament is full of references to polygamy. He saw it as the main source of the oppression of women giving rise to the custom of wife-lending, and therefore to the most exploitative interactions with outsiders.

To become Christians, Mapoon residents had to demonstrate their commitment to monogamous marriage and were settled in village fashion, each couple with their house and garden plot. By 1898 Hey reported about the couples Jimmy and Sarah, Phillip and Ruth (or Ally), Snowball and Stephanie (or Womoo, who died in 1899 at age 20), and Possum and Alma. The latter had been engaged for a year, because it took Possum that long to build the little house which was a condition for the marriage.[14] (Hey did not actually have legal powers to perform marriages.) By 1902 they had 30 houses, covered with corrugated iron. The couples were also required to adopt the European gender division of labour. Aboriginal men showed much resistance to the idea of digging and tending plants which they considered women’s business, as Hey observed:

In the evenings I generally take a stroll into the village and have a chat with each inpidual, and enquire whether the plants have been watered, but that is not thought of. If the women happen to be present it is easy, the men order them straight away to water the plants, orders which are carried out but sparingly. But if the women are absent it is more difficult. They will have a pain in the back or will have sustained an injury of some sort which is not visible but all the more painful, but there will be hope of recovery on the next day, and there is nothing that can be done about it.[15]

In 1905 an outstation for married couples was set up four miles inland from the mission, called Musgrave outstation, in a self-supporting small village with a home and garden for each couple. True to the Moravian model, the couples elected a native teacher as village supervisor, and their school-age children became boarders at the mission school. In 1905 the outstation was led by James, a South Sea Islander who had married a Christian woman from Mapoon. A second outstation near Red Beach was added in 1907.

At the end of 1900 Mapoon received the first children of mixed descent, from Normanton, Burketown, and Thursday Island, allocated by the Protector of Aborigines. ‘We are now a penitentiary’, wrote Hey.[16] Mapoon was declared a reformatory under the Industrial Schools Act which meant that government officials could send ‘neglected’ children there, and the mission received state funding for such children. The dormitory became a core of the mission, and Mapoon became a receptacle for children of mixed descent.[17] Within a year the number of children in the dormitories swelled from 13 to 25 girls and from 15 to 17 boys, and by 1903 there were 41 girls and 20 boys.

The children’s daily routine, orchestrated by the mission bell, was as follows18]:

5am: rise (or 6am in the cold season)

sister opens the dorms

morning work: baking, carrying water and wood, cleaning, making breakfast

6am: breakfast dished out by the bigger children after singing grace

they clean their dishes

morning blessings in the church

7am: school commences (or 8am)

10-11am: practical work

11am: lunch

12-2pm: quiet time for the girls, the boys play outside the mission

1.30-2pm: the girls bathe in the sea

2pm: return to school

4-5pm: fetch wood, cut firewood, gardening,

the bigger girls sweep and clean,

the smaller boys and girls carry manure,

the bigger boys do carpentry

5pm: play until dark

Fencing became a prominent feature of the mission, particularly for the girls’ dormitories. The Chief Protector observed in 1903:

Great precautions are taken to ensure the safety of the children, especially the girls. The garden where they work, play-sheds and dormitories are all surrounded with wire netting so no-one can get in or out, and all the doors are controlled by wires from the Superintendent’s house.[19]

From 1911 to about 1921 boys who were above school age were allocated to a training farm on the Batavia River 15 miles south of the mission, supervised by a Samoan. This spatial organisation of the mission according to age and gender cohorts shows strong similarities to the traditional Moravian upbringing of the Brethren.

Hey became an outspoken opponent of indigenous recruitment on the luggers. He expressed disdain at the way in which young men were recruited into the pearl fishery, and were sometimes left stranded:

Yesterday a sailing boat arrived returning four blacks who had been found on a little island near Thursday Island. The lugger which disappeared completely was stranded and only four of the crew were able to save themselves by swimming.[20]

Hey would have preferred that Aborigines were prohibited from working in the fishery altogether, but the commercial opposition to such a move would have been enormous. Recruiters of Aboriginal labour were already antagonistic towards the new mission. In March 1894 Aboriginal people who were associated with the mission rescued the crew of the shipwrecked steamer Kanahooka, and the missionaries used this incident to argue that the mission was exerting a beneficial influence.[21]

Rather than prevent the employment of mission men on the boats, the mission oversaw the recruitment so that the maximum employment period was set for six months, and the minimum age for recruitment was set at 14. Douglas at Thursday Island had already seen to it that women could not be signed on. The wages earned had to be paid out to the mission:

Having put his wages into the common fund, each boy, as a matter of right, can also draw from the store anything he wants in reason - e.g. fishhooks, lines, turtle-rope, knives, tools, nails, buckets, further supply of clothing and tobacco, and, when he marries, the galvanized iron to roof his house. At Christmas time the store supplies every visitor (including, of course, those from Albatross Bay), with a suit of clothes. Each boy thus learns that he is labouring not only for himself, but for the common good.[22]

In 1904 a third mission was added on the Archer River. Just as the Browns had done before establishing Weipa, Rev. Arthur Richter and his wife served an apprenticeship at Mapoon under Hey before setting up Aurukun.

Hey understood himself as the decision maker for all three missions, in a style of governance which was called by one sympathetic observer as a ‘limited monarchy’.[23] In 1909 he was formally appointed as the ‘superintendent of the North Queensland Mission’, meaning Mapoon, Weipa and Aurukun.

On all our stations the church is in the centre, and the preaching of the Gospel is never side-tracked or made of secondary importance. Everywhere each day begins with a religious service, in fact, religion permeates the whole. Two services are conducted every Sunday, as well as Sunday school and mid-week prayer meetings.[24]

The Baltzer Controversy

From 1907 to 1909 Mapoon mission was embroiled in a controversy over physical punishment in the school, brought to public attention among mission friends in Europe by its former employee Michael Baltzer. Baltzer was a lay assistant at Mapoon and related an incident in a letter to his sister in Strasbourg, who brought it to the attention of others, and eventually it reached the press, was telegraphed around the globe and led to a public inquiry tabled in parliament.[25] (The mission direction in Herrnhut has remained extremely protective in this issue, its records in this affair have not been released to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.)

The incident was over the punishment of a girl at the Mapoon school, who had ‘attacked the teacher in front of the class’. The teacher was presumably Mrs. Ward. Hey, a strict disciplinarian, exercised his ‘paternal right of punishment’ (Züchtigungsrecht), but alleged that the punishment was executed by Baltzer, not himself.

According to Baltzer’s story, embellished through press reportage, the girl was tied to a post for five days and was whipped with a leash for five minutes until she fainted. After she was taken down she was howling and whining for two days from pain. She could neither lie down nor stand up, and could not open her eyes covered in tar.

According to Hey, the girl received 18 to 20 strikes with a riding whip, and did not cry out, nor did she faint. No tar was applied to her mouth or eyes, but a ring of tar was applied around her neck as a symbol of shame, such as was worn by widows to express grief.

The public inquiry called the girl in question and other former mission girls to make witness statements. It concluded that the reports circulated had been exaggerated, but that the chastisement administered was ‘not beyond objection’, and that it was to be hoped that in future punishments would ‘not exceed the normal expectations of school discipline’.[26]

In July 1907 mission director Hennig in Herrnhut felt compelled to take a position on the affair in a circular to the friends of the Moravian mission. He emphasized that the Mapoon mission was not under Herrnhut direction, but controlled by the Presbyterian Church in Australia. He also emphasised that Hey ‘rarely’ used this ‘paternal right of punishment’ on girls above the age of 12, and suggested that Baltzer may be afflicted with ‘tropical madness’ (Tropenkoller) which affects the gall and liver and clouds the judgement. Eventually Baltzer sent a personal apology to the Moravian mission direction, but it was too late to stop the affair from reaching public scrutiny:

The events of the last nine months have compelled me to write to the Board about the affair with Mr Hey, although this is settled, thank God. Mr & Mrs Hey and Mrs Ward have forgiven me in a very generous spirit. I committed a great fault, when I told my sister in Strasbourg several matters, in consequence of which quite false impressions arose to my regret. This mainly resulted from the fact that the conditions here are so perfectly different from those at home. But I assure (the Board) that it was quite contrary to my intentions, when she confided these matters to her friends. It was never my purpose to revenge myself on Mr Hey, as now seems apparent, nor to say anything whatever against the Mission. It grieves me most of all that our friends in Pirmasens have believed the worst. I have contradicted their impression and assured them that we are happy in the work here, no so far have we seen in Mr Hey the least disposition to revenge himself. On the contrary he has only shown us kindness. I was very ill for six months out of the nine during which I was absent from the station, and I have learnt much in that school. May God reward Mr Hey for his sympathy during this time of trouble and for taking us back into his service.

I have resolved to repent like David in the sure hope of finding David’s forgiveness. And who should not find pardon when he repentantly and sincerely pleads for pardon. Herewith I beg the Board to forgive me, where I have grieved you in any way.

A conversation with Mr Hey has shown me that I am in error and have done him wrong. I now hope that I can fulfil my duty with pleasure and in faithfulness, and that I can regain the confidence of Mr Hey and the Board. No work shall be too much for me, if I can help to spread the Kingdom of God and I will gladly apply all my strength to the smallest details of this work. In the hope that this letter will attain its purpose, namely that I shall be forgiven, and that Mr Hey shall stand free again

I am in esteem, M. Baltzer[27]

Native assistants

Christian converts were to play a strong role in the success of the Mapoon mission. Jimmy and Sarah are the earliest Christians at Mapoon to emerge in Hey’s correspondence. They asked to be baptised early in 1896 and underwent baptismal training. Sarah was able to read and read the bible, and also memorized bible passages and hymns. Jimmy, from the Pennefather River, was a boat skipper. He was willing to attest to Christ and ‘disown all sinful customs and habits’ and was ‘not ashamed to visit the sick and pray with them without me telling him to do so’.[28] At his baptism he delivered an engaging public speech in the Pennefather River language before a large crowd, including 400 children. The crowd was so attentive that one ‘could have heard a needle drop’.[29] In the evening the leading personality Oki also gave a great speech, and asked soon afterwards to be baptised. However he was not willing to pay the price. Two years later Hey observed:

Okee still has his two wives and it would not be difficult to part with one if he only wanted to …. I am of the opinion that where there is serious yearning for truth and light, the difficulties in this respect will disappear.[30]

Jimmy became a model Christian. He spent most of his time at Mapoon, but every winter he shifted camp to his home on Pennefather River. Hey encouraged this for reasons of health, and also as an outreach function. Jimmy also helped to establish Weipa, and assisted in the arrest of the killer of Peter Bee (see Aurukun entry). He was the leader of the married couples’ outstation consisting of six houses. The southern outstation with seven houses was in charge of Dick Kemp from the New Hebrides, who conducted daily blessings. By 1910 the residents of this outstation had built their own church.

In July 1898 Hey reported that Jimmy and several other young men were assisting Brother Brown setting up the mission on the Embley River. Sarah remained at Mapoon and ‘still glances towards Zion’.31] However, she also knew how to appeal to the new order if she felt that the traditional order threatened her interest:

A young widow from one of the neighbouring tribes was to fall to Jimmie according to the old customs and traditions and he was pressed from many quarters to accept this widow as his second wife. But as soon as he hesitated and showed an inclination to give in, his wife Sarah came into the mission house and announced it. I at once went into the village and Jimmie explained he had to take the woman, it was the custom.[32]

Hey threatened that if Jimmy bowed to the tradition, he could no longer be his friend. Jimmy, who was leading the Sunday prayer service, was publicly shamed. After the service Hey explained the matter to the parishioners and asked them to stay on ‘to pray the devil out of Mapoon’. Jimmy was excluded from Holy Communion for a period. The woman in question ‘got off with a hiding for which she can be thankful’. (It is not clear who administered the hiding.) Jimmy avoided the Pennefather River in the following year. He became more and more drawn into the Christian world view, even asking for marriage guidance from the missionary. Jimmy’s oldest boy died at age six in about 1904, and he took comfort from Christian convictions.

Possibly because of Jimmy’s model, ‘several young wild men’, including Jimmy’s brother, married girls from the Mapoon dormitory.[33] This strengthened the connections between Mapoon and the Pennefather/Coen River area where Aurukun was established in 1904.

Next to local Christian converts, mixed descendants with Torres Strait and Pacific Islander lineage also played leading roles as ‘native assistants’. For over thirty years ‘Mamoos’ became the ‘right-hand man’ of the missionaries. (In the Torres Strait Mamus is the correct address for a local leader.) Although clearly an important figure, Mamoos only appears occasionally in Hey’s reports and letters, from 1905 to 1910. Hey expresses unreserved praise for this man, who was always so ‘bright and happy’ that once a visiting Aboriginal man asked what medicine this Mamoos was on – he wanted the same medicine to get the same effect on his face.[34]

Hey described Mamoos as ‘in every respect a role model’.35] His wife Lena (or Lina) was a baptised Christian of mixed descent who had attended the Mapoon school and kept the books and diary for the outstation. In 1906 Mamoos was ‘ceremonially appointed as assistant’ and exerted ‘an extraordinary influence on everything.’ The following year he took charge of the fourth sailing boat acquired for the mission and fishing, turtle and trepang had now become the main income for the mission. He was preaching in the local language, and also wrote sermons in English. Presumably Mamoos played a key role in helping Hey to acquire some language competency, although in Hey’s letters the roles are reversed:

the native assistant Mamoos has again proved himself in the past year and is a great help to us in every respect. At times I give him special instruction in order to deepen his understanding of the Holy Scriptures. He has also made a start on developing very simple sermons. Lately it has been his task to translate hymns into the native language and to practise them with the young men.[36]

During 1905 and 1906 Hey also mentioned Barkley as a possible candidate as native evangelist. Other leading figures were ‘Harry’ and ‘Jimmy’.

The Christian Tahitian Harry Price did not speak the local language, but was leading a weekly prayer group for young men as early as 1898, ‘worth more than a second European missionary’. His wage of £60 was met by Ormond College until his death in 1901.[37] Hey related this somewhat embellished story about Harry Price, which contains some similarities with Hey’s own adolescence. He was the son of an assistant preacher for the London Missionary Society, and

One day little Harry was playing at the nearby river with other children, when a little boat approached. The others ran away but little Harry was curious. One of the boatsmen offered him a little gift, Harry reached for it and was instantly dragged into the boat. The boat belonged to an American ship on which Harry was forced to work for two years. He was not badly treated, and inexplicably he reached his home again where his parents and siblings, who had thought him dead, joyously welcomed him. They had thought he had drowned in the river.

Once having tasted the adventure of travel, he didn’t want to stay at home and this is how we came as a very young man to Sydney, travelled to America, and even to London where he saw the Prince of Wales. Later he fell into the hands of a Western Australian pearl fishing company and finally he found his way to Thursday Island.

Until this time he led an irresponsible but unmarred life (ein gleichgültiges doch unbescholtenes Leben) but in the environment which he now inhabited he went downhill rapidly. He led an extravagant life, and to his misfortune always had plenty of money, and yet never felt really happy. …

As a pearl diver he suffered the bends which rendered him incapable for pearling. A certain Mr Jardine who was a partner in the company employing him didn’t want to loose him and appointed him as overseer of his cattle station ‘Bertiehaugh’ on the upper Ducie River about 50 miles southwest of Mapoon.

This is where I first encountered Harry in January 1892 on a perilous first visit, and he so impressed me that I told him if ever he wanted a job to come to me. Mr Jardine ripped him off terribly but he didn’t want to leave his job out of gratitude for the help after his sickness with divers’ bends. One after the other I employed C. Hodges and W. Miller but I always felt that they are not the kind of people we need. As you know we had no assistants after Brother Brown arrived and whenever I thought of taking a trip away I always worried about having a proper assistant here. Miraculously a month before my departure the cattle property on the Ducie was reduced, and one day Harry arrived here to get a lift to Thursday Island. He had with him as a wife a black woman from the East Coast given to him the year before by Mr. Jardine. Mr. Jardine, a highly educated person, himself lived with a half-black woman in a de-facto relationship (in wilder Ehe) and only underwent a civil ceremony a few years ago for the sake of their children. Up here in the north we breathe a different air that only those who live here can understand. …Harry was betrothed. To date there is no civil marriage for natives in the north. Now he has been confirmed for baptism.[39]

Later in the same year, Harry, ‘our faithful assistant’, was reported to be doing outreach work by visiting camps outside the station.

There were a few other Harrys at Mapoon. One was Harry, the brother of Nellie, both baptised in 1901, and both died in 1902. Another was Harry Brown, who had been forcibly removed to Mapoon in 1902 and ‘initially caused only worries’, but became ‘the first half-caste baptism at Mapoon’ in 1910.[40]

The naming of persons through baptism was a mechanism through which they were meant to become full inpiduals before Christ, but of course it renders them anonymous. Missology did not teach missionaries to retain at least an identifying tribal name, or to respect the significance of their indigenous names. It also did not prepare them for cross-cultural influences. Only rarely did missionaries think of adding the baptismal name to a tribal name. Jimmy at Mapoon is a case in point:

Deinditschy is Jimmy’s real name, his father, brother and sisters carry this name. He was named Jimmy by a pearl fisher who found his real name too long and cumbersome. In order to prevent misunderstandings I have recorded both names because we have several Jimmies. And I also plan to maintain two names for all baptised Christians. As far as I’m aware Deinditschy has no real significance. It is a very old name and there is a little bird here that carries the same name. I was unable to ascertain whether the name has anything to do with the bird.[41]

Aboriginal totemistic beliefs would suggest that if there is a bird by the same name, this would clearly be of the greatest significance – indeed, a sufficient explanation for a tribal name. On the other hand, ‘Dein’ may also indicate a foreign influence, like the Dayng occurring in Yolngu names at Arnhem Land adopted from Macassan. Often the names by which indigenous people were addressed were simply the correct way of addressing them, like ‘Mamus’, rather than personal names.

The work of a missionary

Next to supverising the building and conduct of the mission Hey was always busy with paperwork. Until 1919 the mission reported both to Herrnhut and to the Melbourne committee, as well as to the government, which granted a subsidy of £250. Hey complained about having to serve two masters. It was a condition of the government land grant that improvements on the land were performed every year. Besides this missionaries were also often consulted for expert advice by government and by ethnographers, and specimen collectors also often asked missions for help. He also kept the church records for births, deaths, marriages and baptisms, and allocated a birthday to each child at the school, nicely spread over the calendar. There were also frequent official visitors.

Archibald Meston as Special Commissioner of Police spent a whole week at Mapoon and did not impress either of the missionaries there:

I only had to spend one night in the same bed with him because I left for Thursday Island the next day with my dear wife. Mr Meston and Brother Brown could not quite get along with each other. When I visited Mr Meston a month later at Thursday Island he was very dismissive about Brother Brown, and I since heard that he showed the same attitude elsewhere, even in public. Later I heard from Brother Brown that Meston emboldened himself to say to Brother Brown in the presence of others that he should pray less and show his Christian spirit more in deeds. … Brother Brown asked Mr Meston to inspect the site for the new mission, but he refused. During his whole time at Mapoon he visited neither the church nor the school, and bothered neither with the missionaries nor with the Aborigines but tried to collect as many traditional weapons as possible which he said bring in a lot of money. He still hasn’t honoured his promises to our blacks to send gifts in return. As he himself said he has killed many a blackfellow in his time, but his report portrays something else. It suggests that he is the right man in the right place. …. Mr Meston is a great speaker and knows how to handle a pen. He has been trying to get a job as inspector for a while. I have his report here ….. I am sorry to say that it contains much that does not accord with the truth, and that he has been asked by many quarters to show proof for certain of his statements which has not been able to do. It went so far that the government was forced to send another inspector on the same journey to find out who was right, Mr Meston or his opponents (that’s how money is squandered).

Two years later Hey noted with some satisfaction that the scandal over Meston’s Fraser Island mission ensured that he was not taken seriously by anyone.[42]

Public criticism was of course damaging for missions who needed public support. The mission received donations from various organisations in Australia. By 1898 Hey admitted some fatigue of public relations work, which he felt took was detrimental to focusing on spiritual life.[43]

At this time, too, Hey was faced with the withdrawal of the government’s steamer service to the Mission. He had to either engage Hodel Company at Thursday Island or purchase a mission boat, which he had long considered necessary. They obtained the J.G. Ward, which in 1910 was handed to the new Presbyterian mission in Western Australia and replaced with the a larger boat, the Minnie, in 1912. It was used for gathering trepang, which became a profitable industry for the mission, and in 1914 the mission acquired a new motor boat called Namaleta (Messenger).

The chief protector visited at least once a year to inspect the school. After the death of Douglas in 1904 and the replacement of Roth with Howard in 1906, relations with the government deteriorated. Hey felt that there was some high-level attempt to trap the mission effort by sending incorrigibles, and that the government made unreasonable demands for trained labour, attempting to commandeer people onto and away from the mission. Howard paid his compliments to the discipline at Mapoon with an entry in the school book:

Was delighted at the marked improvement in the school, the exceptionally tidy and clean appearance of the children. This nice demeanour and general progress which I must in justice say excels that of any of the Aboriginal schools I have visited

(signed)

H. B. Howard, 7 December 191044]

But Hey continued to report about the ‘enmity and envy of certain officials who continually seek to destroy the mission.’ He felt that ‘many of our officials have little understanding and even less interest in the maintenance and reinforcement of economic independence among Aborigines’. The budget for Aboriginal affairs was increased from £18,000 to £25,000 between 1913 and 1914 ‘but the government scorns the only possible remedy with blind determination.’[45] What he felt was needed was the encouragement of independent economic activity instead of hiring people out as cheap labour.

At one of the outstations Jack Charger organised the trepang fishery with good profits and ‘the result of the work belongs to the Aborigines not the mission’. He was a South Sea Islander married to a Mapoon woman who helped him preparing sermons and the two lived on their own farm at the outstation.

While the general understanding was that such couples were living on their ‘own’ plots of land, the title to such land was never secure. In 1911 Hey observed that the houses were constructed by the mission and remained its property.[46] But in 1913 the southern outstation farm was divided into two and was given to two married couples as their property (mit Haus und Hof zum Eigentum übergeben). ‘So far we have not got ourselves to officially register the Aboriginal names of the outstations’.[47] As a matter of fact, Hey was unsuccessful in gaining secure title to land for these plots.[48] In 1936 a Presbyterian visitor observed that ‘all the cottages at the outstation have been built and purchased by the natives’ with money earned from external work.[49] This was commendable, but thirty years later the residents of Mapoon, having built and paid for the houses, were evicted from them.

World War I and the withdrawal of German missionaries

Hey had been naturalised in 1898, after the birth of his second child, and this proved auspicious when World War I erupted and enemy aliens were interned. Although his formal citizenship spared him from internment, the writing was clearly on the wall for German missionaries. He suffered three house searches as a result of rumours that a German in the Gulf of Carpentaria was spreading propaganda. On one occasion the captain of the supply boat, who had known him for 25 years, refused to land at the mission. By 1919 Hey felt compelled to retire so that the mission could be conducted by Australian Presbyterians.

Embittered by the anti-German sentiments festering during the war, he wrote to Herrnhut in 1920:

The mail seems to work again but the effects of this terrible war will be felt for years to come. The time has not yet come where I can relate my experiences of the last four years in letters. This is not because of a fear to honour the truth, but because I do not wish to do anything which could damage the purpose of the mission. I have always tried to take as much as possible a neutral position, mindful towards the positive. In that spirit I have upheld and honoured my oath of loyalty as an Australian citizen because only that permitted me to put the lie to those who maintained that a German could not be trusted and believed. …..

Most German pastors were arrested and interned, many have already been extradited. They will not tolerate German missionaries in the future. I regret not being able to stay in the tropics, but the Presbyterians should continue the mission. They will learn a lot from it. At the moment Mapoon is the only NQ mission without debts.[50]

Just before his retirement Hey experienced another traumatic event that shook the confidence of missionaries when Rev. Robert Hall was killed at Mornington Island. Hall had been Brown’s assistant at Weipa from 1909 to 1913. He was a New Zealand farmer who received three years’ missionary training in Adelaide and was ordained by the Presbyterian Church to commence the Mornington Island Mission in 1914 with his wife Catherine. Mornington Island Aborigines attacked the mission staff in October 1918. Hall was killed and his assistant Owen wounded, and ‘Mrs Owen and Mrs Hall defended the mission house for several days against a hostile section of the natives’ Hey felt that the extensive contact with Malays was to blame for this violence.[51]

|

Old Mapoon: full of memories and attachments |

.bmp) |

| Photos: Regina Ganter 2007 |

In 1919 both Brown and Hey left the North Queensland mission. Brown moved to the United States, and the Heys retired to Sydney after 28 years at Mapoon. The Moravian church devolved its superintendence of the missions to the Presbyterian Church of Australia, formally ending any German or Moravian involvement in the North Queensland mission.

Presbyterian Mission

Hey was unhappy with the way his successors conducted the North Queensland mission. He wrote to Herrnhut in 1920 that Brother Love at Mapoon was ‘going the wrong way’ by allowing mission residents to work outside the mission. He thought this was entirely unnecessary, since the mission was in good financial condition and was ‘financially supported throughout Australia’. Hey observed with some disdain that both Love and Bowsfield, who had replaced Brown at Weipa, were university trained, ‘very educated but not suitable for the work’. Mrs Bowsfield ‘never went out without gloves out fear of being touched’. The Holmes were still at Aurukun, but their son as assistant missionary was in Hey’s opinion damaging the mission by delivering young men to the pearl fishery.[52]

| Signs of World War II | |

|

The late William Parry examining an old Japanese sea mine near the mission site. During World War II there were several incidents involving allied aircraft near Mapoon. In September 1942, a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber crashed near the Pennefather River and people from Weipa and Mapoon organised the rescue of the crew. |

As a Presbyterian mission Mapoon never had the same permanency of staff. Rev. James Robert Beattie Love, the son of a South Australian minister took over in October 1919 and remained for eight years. (Love was also associated with Kunmunya in Western Australia.)[53] The five missionaries who came after him remained for five years at the most, until Frank Alan Cane arrived from 1940 to 1948, and then nine missionaries stayed for three years or less each until the last missionary, Garth Filmer arrived from May 1958 to July 1963.[54] The layout of the mission barely changed in all this time.

By 1930 some four hundred baptisms had been performed at Mapoon and its church had sixty members, many of them settled as couples in cottages with their own garden plots. The local community with a traditional responsibility for the country merged with many mixed descendants who had been forcibly removed to Mapoon. For most of its residents Mapoon had become the only home they knew. The mining boom completely undermined the security of that community. From 1959 the community was ‘encouraged’ to move, and in 1965 Comalco’s mining lease was extended to include the site of Mapoon and the Queensland government insisted that the whole community be removed to a different location, called ‘New Mapoon’ near Bamaga. The Mapoon residents resisted the move, and felt sorely let down by the Presbyterian mission board and their missionary Garth Filmer, who closed down all facilities, including the church, school, store, and health service. In November 1963 the community members were placed under armed guard, and the houses set on fire and bulldozed.[55] The Mapoon people never accepted their relocation and since the 1970s have gradually re-established themselves at Old Mapoon, with the Marpuna Aboriginal Corporation.

[1] Grope, Lesley, ‘Cedars in the Wilderness’ LutheranChurch of Australia Yearbook 1987, pp 25-57.

[2] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 8.

[3] Bos, Robert ‘Mapoon – 100 Years’Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress, (MS), Thuringowa, 1991.

[4] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 9.

[5] Hey to Connor, 7 March 1892, Mf 186 AIATSIS.

[6] Hey to Connor, 7 March 1892, Mf 186 AIATSIS

[7]Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 9.

[8] Harris, John, One Blood - 200 years of Aboriginal encounter with Christianity: a story of hope, Sutherland, NSW, 1990, p. 487

[9] Hey to Connor, 4 October 1895, Mf 186 AIATSIS.

[10] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 11.

[11] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1909, Mf 186 AIATSIS.

[12] Ward, Arthur, The Miracle of Mapoon: or from native camp to Christian village, London, Partridge, 1908, p. 73.

[13] Hey to O’Connor, n.d., around August 1892, Mf 186 AIATSIS.

[14] Hey to La Trobe, 8 August 1898, Mf 186 AIATSIS.

[15] Hey to La Trobe, 8 August 1898, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[16] Hey, Annual Report for 1900, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[17] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 13.

[18] Richter, Annual Report for Aurukun for 1903, to La Trobe, Mf 171, AIATSIS.

[19] Walter Roth, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aborigines, Queensland Votes and Proceedings, 1903, Vol. 2, p. 470.

[20] Hey to Connor , 4 July 1893, Mf 186, AIATSIS. (Presumably meaning O’Connor.)

[21] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 11.

[22] Walter Roth, Annual Report of the Northern Protector of Aborigines, Queensland Votes and Proceedings, vol. 2, 1902, p.555.

[23] Harris, John, One Blood - 200 years of Aboriginal encounter with Christianity: a story of hope, Sutherland, NSW, 1990, p. 491

[24] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 26.

[25] On 23 August 1909 John Douglas gave evidence in parliament, recorded in the Queensland Hansard, and the Home Secretary consented to a public inquiry.

[26] W. H. Ryder (Under Secretary) to P. Robertson, Presbyterian Church Brisbane, Herrnhut Archives, R15.V.II.a.3.

[27] Baltzer to Berthelsdorf (Moravian Mission Board) 30 Aug. 1908, Herrnhut Archives, R15.V.II.a.3.

[28] Hey, 3 April 1896, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[29] Hey, 30 October 1896, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[30] Hey to La Trobe, 28 March 1898, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[31] Hey, July 1898, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[32] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1900, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[33] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1900, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[34] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 13.

[35] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1905, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[36] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1910, and previous reports, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[37] Lees, W.M., The Aboriginal Question in Queensland – How it is being dealt with, Brisbane, Government Printer 1902, (n.p.).

[38]Actually Jardine’s wife was from a leading family in Samoa, sometimes referred to as a ‘Samoan princess’.

[39] Hey, 8 August 189, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[40] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1910, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[41] Hey, n.d. presumably between June 1899 and Jan 1900, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[42] Hey to La Trobe, 28 March 1898, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[43] Hey to La Trobe, 8 August 1898, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[44] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1910, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[45] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1913 and 1912, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[46] Hey, Annual Report January 1911, Mf 186, AIATSIS.

[47] Hey, Annual Report for Mapoon for 1913, written on 12 January 1914. Hey noted that the place on which the outstation church stood was called ‘Wantscha’. The farm developed by Lui was called ‘Phoweranga’, and the new outstation on the Batavia River was called ‘Timbearanama’.

[48] Wharton, Geoffrey ‘The Day the Burned Mapoon: A Study of the Closure of a Queensland Presbyterian Mission’ BA thesis, University of Queensland, 1996, p. 39.

[49] Nelson, N. F., Record of visit to mission stations 1936, in Wharton, Geoffrey ‘The Day they Burned Mapoon: A Study of the Closure of a Queensland Presbyterian Mission’ BA thesis, University of Queensland, 1996, p. 42.

[50]Hey to Herrnhut, 19 January 1920, MD825 Missionsdirektion Personalakten, Nicolaus Hey, Herrnhut Archives.

[51] Kirke, G.K. and C. Radcliffe, ‘Presbyterian Church of Queensland, Missions to the Aboriginals – Past and Present’, Brisbane, Black and Flack Printers, 1924, p. 4. Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 17.

[52] Hey to Hennig, 7 Oct 1920, MD825 Missionsdirektion Personalakten, Nicolaus Hey, Herrnhut Archives.

[53] Hey, Rev. J. N., A Brief History of the Presbyterian Church’s Mission Enterprise among the Australian Aborgines, Sydney, New Press, 1931, p. 18.

[54] Wharton, Geoffrey ‘The Day they Burned Mapoon: A Study of the Closure of a Queensland Presbyterian Mission’ BA thesis, University of Queensland, 1996.

[55] Harris, John, One Blood - 200 years of Aboriginal encounter with Christianity: a story of hope, Sutherland, NSW, 1990, pp. 493-497.