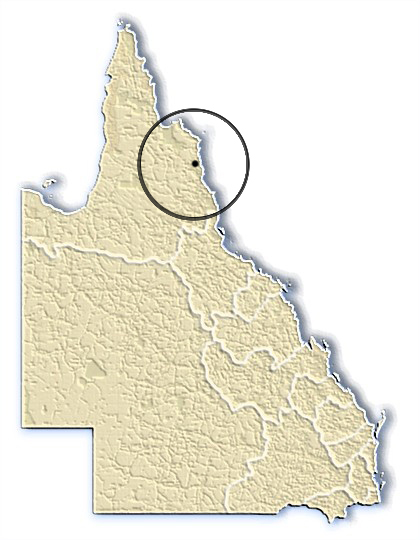

Bloomfield (Wujal-Wujal)

Bloomfield River mission in the Daintree commenced as a well-funded government initiative during a period of rapid settlement in the Cooktown region. It was then devolved into Lutheran care and underwent a parallel development with the Lutheran mission at Mari Yamba. Two successive missionaries foundered in health and spirit at Bloomfield. When the mission was wound down in 1901 the Kuku Yalanji refused to be shifted to Cape Bedford, and although the reserve was revoked, they remained in the area in a number of small camps. In 1957 it became Wujal-Wujal and still exists as an Aboriginal community. Because it became a Lutheran mission only in 1887, it celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1987.

Government initiative

The establishment of the Bloomfield mission took place in tandem with the establishment of Cape Bedford Mission by the indefatigable Johann Flierl. Within months of the establishment of Cape Bedford, the Queensland government announced that it had set aside a second reserve on the Bloomfield River, 45 miles south of Cooktown. This was confirmed by a telegram from Normanton by Sir Samuel Griffith on 18 March 1886, advising that Louis G. Bauer had been appointed as superintendent for a year at a salary of £300 and provisions".[1] This was liberal funding.

The establishment of the Bloomfield mission took place in tandem with the establishment of Cape Bedford Mission by the indefatigable Johann Flierl. Within months of the establishment of Cape Bedford, the Queensland government announced that it had set aside a second reserve on the Bloomfield River, 45 miles south of Cooktown. This was confirmed by a telegram from Normanton by Sir Samuel Griffith on 18 March 1886, advising that Louis G. Bauer had been appointed as superintendent for a year at a salary of £300 and provisions".[1] This was liberal funding.

The initiative emanated from the rapid development of this region by pioneer settlers. Pastoralist William Hann had explored the area in 1872, and in June that year the first selectors of Portions 191 to 195 at Weary Bay were George Hislop and the Bauer family, with Frederick, his son Louis and Annie Bauer each selecting a portion on the northern side of the Bloomfield River. Frederick Bauer established the Bloomfield River Sugar Company with imported Malays. At nearby Ayton a small settlement emerged around the plantation and sugar mill with a police station, store and pub. Aborigines and Chinese became attracted from the meagre tin fields, and tension developed between the Chinese and the Malays. Into this ethnic minefield stepped the formidable Moravian Friedrich Hagenauer on a tour of north Queensland on behalf of the Presbyterian Church and the Aboriginal Committee of Victoria, and proposed the immediate and urgent setting up of a (Moravian/Presbyterian) mission in order to halt the blackbirding of Polynesians:

Why not endeavour to befriend the many thousands of Aborigines in North Queensland, who live in their own country and can be made very useful if the right means are adopted, and the Law and Gospel joined together?[2]

| Bloomfield River Mission House 1886 | Bloomfield mission, 1880s |

|

|

| Source: 103575 JOL, State Library of Queensland | Source: SLQ (Picture Australia) |

The Queensland government moved to set aside Aboriginal reserves at Cooktown and on the Bloomfield River, but Premier Griffith declined to make a financial commitment beyond the first year of operation, so that negotiations with the Presbyterians failed. Moreover, the move met with local resistance from white settlers in 1885:

The government is offering to the Aboriginals the temptation for evading employment provided for them, for the easier though more precarious loafing about the township and homesteads in the vicinity’.[3]

Possibly to break the resistance, Louis Bauer was appointed as the mission’s superintendent with a generous remuneration which allowed him to erect his own quarters to supervise a station which he anticipated would become a prosperous tropical farm, growing tea, coffee and tropical fruits in commercial quantities. He was assisted by a married couple for whom quarters were also erected. The Bama were given rations of ‘a small portion of dough uncooked, sweet potatoes raw, with twice a week the offal of a bullock, namely head, feet, paunch and intestines’.[4] Hislop was to remain hostile to the mission.

Meanwhile Johann Flierl had already been given speedy permission to take on the Cooktown reserve, within two weeks of his inquiry. No sooner had Cape Bedford been established, that Premier Griffith offered the running of Bloomfield mission to the Lutherans on the same terms as CapeBedford – meaning that the government intended to wind back its support after the first year. The Victorian Moravians had shown an interest in setting up a mission in North Queensland (and did so in 1891 at Mapoon), the Queensland Lutherans associated with Hermannsburg (UGSLSQ) were setting up a mission at Mari Yamba, and declined Flierl’s request. Neuendettelsau also declined, so the South Australian Immanuel Synod were eventually persuaded to take on the new mission so close to the one just commenced at Cape Bedford, which was now fully devolved to Neuendettelsau. Mission Inspector Deinzer in Neuendettelsau remarked that he had been given the ‘thin cow’, and the Immanuel Synod took the ‘fat cow’, because Bloomfield held so much promise for agriculture.[5]

The Immanuel Synod re-assigned their tried and tested pastor Carl A. Meyer, who had spent time in the Dieri mission at Cooper Creek (South Australia) and held the fort at Cape Bedford until its missionary Pfalzer arrived in September 1886. Meyer then moved to Bloomfield to replace Bauer in January 1887 together with his wife Emma and the Dieri lay missionary Johannes Pingilina.[6]

Meyer at Bloomfield 1887-1892

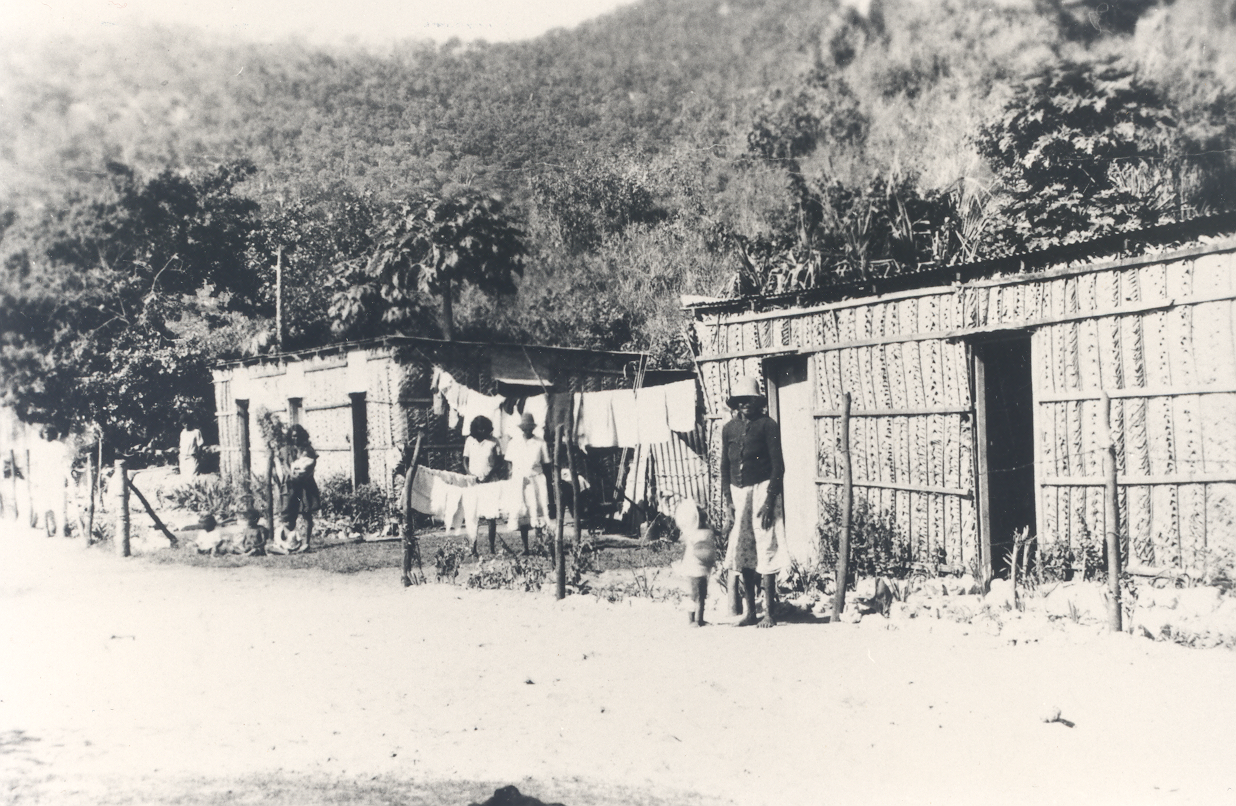

Initially Meyer, like every other visitor to Bloomfield, was greatly impressed with the lush fertility of the site. It had two living quarters, 17 small native dwellings, and a thriving garden on 640 acres of gazetted reserve land. Bauer and two assistants stayed on until July, and in August 1887 Ernst Jesnowski and his wife and child arrived. Meanwhile Pingilina became disillusioned with Meyer, who failed to take his views seriously, and left for Elim at the end of the year. In 1888 the staff was again increased with J. H. Koch from the Immanuel Synod mission in Central Australia as builder, with his wife and child, and H.G. Steicke who had been assisting at Elim. The mission staff now consisted of three German families and a bachelor. They increased the milching herd to 60 head, and grew and banana, coffee, tea, maize and other crops, including tobacco as rations for Aborigines.

| Aboriginal dwellings in the Daintree | |

|

.bmp) |

| Photos by courtesy of Mossman Gorge community |

Meyer observed that the Kuku Yalanji did not speak a word of English, and attempted to learn the language and to translate bible texts, but blamed his informants for giving them the wrong words. Instead of ‘thou shalt not commit adultery’, the Kuku Yalanji sixth commandment became ‘thou shalt not be married’. By their second Christmas, they were singing Luther’s ‘From heaven above to earth I come’ in Kuku Yalanji together with seventy Bama.[7] There were about 130 adults and 42 children in the mission area. In March 1889 the Queensland government reserved a further 50 square miles as ‘hunting ground’ for Aboriginal people, to the surprise of Meyer. This was soon to raise the ire of local timbergetters.

The government also sent 300 coconut seedlings to encourage copra plantations in 1890. Despite Bloomfield’s lush appearance, intensive agriculture exhausted the soil after a few years. The Ayton sugar plantation suffered the same fate, and wound up with a loss of £100,000 in 1890. Rain was concentrated in a short three-month period associated with flooding, and the area was prone to malaria. Agriculture seemed to be the major occupation of the mission.

Meyer taught bible history and translated some bible stories into Kuku Yalanji. Koch looked only after the farm work. Jesnowski, who was slow in acquiring the languge, supervised the children at agricultural work assisted in the school, which was being conducted in English, using the English (Latin) rather than German script.

Jesnowski, Koch and Steicke adjusted their working hours to those required of Aboriginal workers, from 8.00 to 11.00 in the morning and from 2.00 to 5.00 in the afternoon. Meyer was unhappy about this but felt powerless, and there was constant bickering about trifles, such as whether the raisins Koch obtained from the mission store were good enough to eat. In December 1889 Meyer handed in his resignation because of tension with the mission staff. The committee declined to accept his resignation and asked the staff to comment. There were a number of problems. Meyer found Koch ‘difficult’ because he wanted to be allocated some land for himself, and Steicke ‘too friendly with the blacks’. Pingilina, who had been forced to return to Bloomfield in 1888, observed Jesnowski and Meyer frequently drinking and arguing. There was also hostility from white settlers who made complaints to the government, and it was reported that the Bama disliked Jesnowski. Mrs. Jesnowski succumbed to consumption in July 1890, and by September Jesnowski wanted to leave in order to re-marry. Steicke handed in his resignation over a ‘scandal’ regarding his involvements with Aboriginal women.

Jesnowski was sent away, but Steicke stayed on. Despite his liaisons with Aboriginal women Meyer appeared to place confidence in him, perhaps because of his ability to get along easily with Aboriginal people. In October 1888 Steicke had run the mission for a month during Meyer’s absence, although Steicke was not a full member of the mission whereas Jesnowski was. In February 1891 after the local Bama had come back to their seasonal camp at the Bloomfield River, Meyer investigated the ‘scandal’ with Steicke. It had been alleged that he had crawled into an Aboriginal women’s hut at night. Meyer interrrogated the witnesses, and found that there was not enough evidence to dismiss Steicke. Either the Bama supported Steicke, claiming that it had been too dark to see who it was, or Meyer protected Steicke.

Meyer himself came under increasing public criticism, so that by November 1891 he himself thought it was best for him to leave. He ‘had unwittingly come into conflict with the regulations of the Queensland Government regarding the Aborigines’.[8] A beche-de-mer recruiter had requested labour, and Meyer had accepted a £15 cheque for the mission. He could only procure three interested men, and both the recruiter and others turned against him, accusing him of accepting bribes and of drunkenness. The government made its continued funding contigent on Meyer leaving. He departed in January 1892 to become a school teacher, first at St.Kitt’s and then in Steinfeld until his retirement in 1898. He died in 1912.

The mission effort was concentrated on the school conducted in English, and agricultural work. Financially the mission was sound, with a government subsidy supplemented by the sale of coffee and other produce. Aboriginal workers were paid in food and tobacco, and received a meal after Sunday service. The Bama continued to fulfil their ritual obligations, and if there was an important traditional event the school children also left the mission.

Hörlein at Bloomfield 1891-1901

Meyer was replaced by Johann Sebastian Hörlein arriving in July 1891, straight from Neuendettelsau. In September Hörlein assumed the management of the mission, and immediately implemented changes. He wanted to give it a distinctly German imprint and sought to keep it free from English members, otherwise it might acquire an ‘English patina’. It was to be known as ‘Evangelisch-Lutherische Missions Station’, not ‘Lutheran mission station’. Against government policy, he instructed the new teacher Curt Schulz to teach the school in ‘Wodjall’ (Kuku Yalanji).[9] The house of the Koch family had to be relocated alongside the other houses, for the sake of ‘exterior orderliness’, and the working hours were to be increased to 45 hours per week. Steicke resigned as a result, and the Kochs left in early 1892.

|

Johann Sebastian Hörlein at age 20, graduating with Johann Mathias Bogner from the Neuendettelsau seminary |

|

|

| Source: Box 6, Lutheran Archives Australia |

Hörlein suggested his Neuendettelsau comrade Johann Matthias Bogner as a replacement for Meyer, and Bogner arrived in December 1891. So now there were no families among the mission staff, only two unmarried pastors and a teacher who was engaged to an English girl at Ayton. Each pastor had a ‘little daughter’ who could speak some German, Timbora, who had been brought by Meyer, stayed with Hörlein, and Tokopati stayed with Bogner. ‘They help in the kitchen, cheer us up, and attend Sunday service.’[11]

Not long after Hörlein’s arrival the two new Moravian missionaries for Mapoon visited Bloomfield. ‘The amenities are impressive but there is no hint of missionary work’, reported Hey to his mission committee. The criticism leaked back to the Immanuel Synod, and Hörlein expressed surprise that the the Brothers were so critical - they had seemed very friendly while they visited.[12]

A meticulous account was kept (in English) of Aborigines employed and rationed at the mission station, to record the government rationing, an important source of income for the mission. Its monotony is not altogether convincing, but it suggests that rations were dealt three times a day, including on Sundays. It shows that there were always more women than men at the station, with a generous number of children, of whom less than half attended the school. It also suggests that school was not necessarily always held. The figures are not altogether convincing because they are so neatly comprehensive. They suggest that the government subsidy of £200 worked out to less than a penny a day for each person. Bauer’s rations in the first year worked out between 3d to 5d a day per person.

The Boomfield Misson Record Book, June 1894

Aboriginals fed: 1st June – 30th 1894

| A page from the Bloomfield Mission Record Book, December 1894 |

|

|

| Source: Bloomfield box, Lutheran Archives Australia |

Bogner married in 1893 but his wife took ill and the couple departed in January 1895. His replacement was another arrival from Neuendettelsau, Johann Christian Mack (born 1866, Mack later went to Iowa, USA[13]). Mack became the school teacher of up to 25 children, in English, as required by the government. He was considered impatient and threatening. The Bama found Mack ‘too much row’.[14]

Physical punishment was apparently introduced in the school during Hörlein’s period, and Aboriginal parents strongly objected to it. Hörlein was incredulous to find that the Bama never used physical punishment on their children, even if these were naughty or threw a tantrum. For him it was proof that Aboriginal parenting lacked paternal discipline, it was merely ‘monkey love’. Whenever the missionaries punished a pupil the child would scream, causing the adults to rush in to make a scene, yelling at the missionaries to lay off. Eventually the rainmaker declared that if the missionaries persisted in striking any of their children he would refuse to make any more rain.[15] The missionaries persisted. The rains failed. But the mission had a 40-foot well with a force pump for irrigation.

| Pastor Hörlein and his congregation at Bloomfield |

|

|

| Source: Box34-36 7032 Lutheran Archives Australia |

Hörlein was also amazed that the women did not necessarily support each other if one of them ran away from her husband. Sometimes women came to the mission to shelter, often with terrible wounds, but usually returned to their husbands after a few days. Hörlein regretted that there was no woman among the staff who could look after women and girls, and consequently none could be taken in, to resist the traditional practice of promised marriages of child brides. The school appears to have been run mainly for boys, who resented the things they were supposed to learn. They argued that this kind of learning was for whites, and put their own spin on the lessons. To the question ‘what did God create on the first day?’ they would answer ‘maji’ (food).

In May 1891 Meyer had a stand-off with the elders over a payback. A young man who was dying identified the person whom he held responsible. After his death the accused was lured into the camp and attacked in a wild flurry of spears. He saved himself by running to the mission house with four barbed spears lodged in his body. The young man’s funeral involved the severing of the head and opening the corpse, which revealed that a piece of spear had penetrated the liver. The body was then cremated. Meyer castigated the elders for attacking a man who had nothing to do with the death. The elders so resented his interference that they threatened to all leave taking everyone, including the children, with them.

Archibald Meston’s report as special commissioner in 1896 was rather scathing of Bloomfield. He thought it had been extravagantly funded with little to show. During its first three years it cost the government more than £1,600 and the Immanuel Synod £1,963.[16] It had a smithy, a saddle making workshop and a good supply of leather, bee keeping equipment and a large collection of tools. Meston was unimpressed with the quality of the soil, ‘some evil genius seems to have presided over the selection of sites for all the Mission Stations in Queensland’.[17] At the time of his visit there was a bora ceremony and all the school children were absent. Some were at the Chinese camp, and others on the tin mines. He also suggested that the rations given were too meagre. The negative report dampened the spirit of the missionaries. Hörlein was in South Australia to get married at the time of Meston’s visit, and Meston understood two German assistant missionaries to be in charge. Actually, according to mission Inspector Kaibel, Steicke had been left in charge, which must have been a slight for Mack.

The newly appointed Chief Protector of Aborigines, Dr. Walter Roth visited the mission in 1897 or 1898. He was keen to determine how the government subsidy of £200 was spent. Again Hörlein was absent during this important visit, and Roth’s report was based on information supplied by Mack (referrred to as Mr Max in the report). Roth determined that the two assistants alone cost £150, leaving only £50 for the Aborigines (and nothing for the missionaries). Mack volunteered that they also received £400 per annum from South Australia, leaving Roth to wonder whether the government ought to continue to top this up.[18] The missionaries were receiving less than £50 pocket money, so that staff expenses must have been below £250. The £200 government allowance could not have covered the expenses of rationing, let alone running a school, housing and other associated costs. If the daily station records are even approximately reliable, then the government subsidy for rations should have been three or four times that amount. It certainly appears that the Lutheran communities in South Australia contributed considerably to the feeding of Queensland Aborigines. Perhaps because of this persistent questioning from the government about how the mission funding was spent, Mack suspected that Hörlein and mission director Rechner were mismanaging mission funds. Mack felt sidelined and became very critical of the mission.

In January 1900 Anne Hörlein’s malaria returned and she became unable to tolerate any kind of noise in the house. Hörlein asked Mack to move out of the mission house into a cottage. Mack felt increasingly alienated and distanced himself from Hörlein, When Hörlein himself was attacked by fever only Steicke was there to look after them. In February Anne approached death and Hörlein took her to the hospital in Cooktown. Mack ignored their hasty departure, and Hörlein never forgave Mack for not saying farewell to his wife. Eventually the two missionaries only corresponded in writing with each other.[19]

The final act

As soon as Hörlein had left for Cooktown, Mack went up to the mission house to check on Steicke. Steicke refused to let him in, and on the second day actually struck Mack. Mack now accused Steicke of abusing the mission girls and informed Chief Protector Walter Roth who promptly visited the station. Accordingt to Mack, Roth was incredulous to find Steicke in charge.

In 1899 Hörlein had mentioned three orphan girls at the mission, but by 1900 the mission had six ‘house girls’ who could read and write. It appears that these girls lived in the mission house with the Hörleins. Mack wrote to the committee about his impression of Steicke who he thought had been at the mission for three years:

Thus I had to stand by while these poor girls, who had suffered much (at least some of them) during their three-year ordeal, became the prey of a godless beast without conscience, being exposed to a depraved, shameless man for five weeks. It is putting the wolf among the sheep to strangle them. On the first and second day after Hörlein’s departure I immediately went to the big house but was turned back each time as all the doors were locked. Steicke told me I had no right to enter, everything had been turned over to him. The girls were not permitted to leave the house, and they were not allowed to go to school either. ….. It would be better to have nobody here than such a rat. When the police inquired whether he had any connection with the girls he unhesitatingly said, yes.[20]

In that year, too, one of the mission staff fathered a child with an Aboriginal woman.[21] How Steicke managed to make himself indispensable at the mission is a puzzle. Both Meyer and Hörlein had repeatedly made veiled references to ‘scandals’ regarding his relations with Aboriginal women, but while the government received complaints about Jesnowski and Mack, the Bama apparently never complained about Steicke. Because the missionaries were so guarded in their reports, it is impossible to determine whether Steicke had a permanent relationship with one woman, or several sexual liaisons, or abusive relationships. Meyer observed that he was ‘too playful with the blacks’ (July 1890) and that his ‘interaction with the blacks was not conducive’ (September 1890). In September 1890 he wrote: ‘Steicke must go! Decency forbids me to enter into details. There are no doubts.’ The following February he was observed crawling into a women’s hut, but either the Bama closed ranks or Meyer turned a blind eye. In December 1891 Hörlein had heard that Steicke was ‘very familiar with the black women’. Despite all this, both missionaries kept re-employing and trusting him. Surely a central purpose of a mission was to shelter indigenous people from abuse by whites, and particularly from sexual abuse.

Why did neither of the two missionaries take their own concerns over Steicke seriously? According to Mack he lived with a black woman at Ayton in the early 1890s, and in the local community he was ‘not considered any better than a blackfellow’. He was also ‘paid at blackfellow’s rates’.[22]When Hörlein’s wife was sick, Steicke looked after her. When Pingilina was in trouble with his wife, Steicke accompanied him to win her back. He spoke the language better than Mack. Was he perhaps a social conduit into the indigenous community, like Pingilina had been?

Hörlein returned to the mission broken in spirit and despondent after the death of his wife. He wanted to leave. At the same time the Queensland government was taking more control of missions with government-appointed trustees, and Roth started to draft amending legislation to proceed against cohabitation with Aboriginal women and curb mixed race marriages. It was time for a serious re-assessment. The mission committee sent Pastor Kaibel to inspect and report on the mission. He basically accepted the judgement made by Roth that there had not been a single baptism at Bloomfield and the mission was a spectacular failure. The government subsidy for 1900 was withdrawn and in August 1900 the Immanuel Synod decided to wind down the mission. Mission inspector Gössling in Brisbane asked for the Bloomfield girls to be sent to Mari Yamba, but Hörlein wouldn’t hear of it:

Nobody has the right to take them away, I will not suffer it. It is a slave trade, and an Aboriginal will not be replanted into a new country without damage.[23]

But that is just what was going to happen. A few months later the UGSLSQ synod supporting Mari Yamba also decided to withdraw from its mission venture near Proserpine, and in fact the Mari Yamba people were taken to Cape Bedford, some of them via Bloomfield. The Anglican Church declined to take on Bloomfield, but Hörlein took some of the Bloomfield mission children to the Anglican mission at Yarrabah, when he had finally run of food. [24]

Struggling with illness and depression Hörlein was still harvesting and cleaning coffee and sending the beans to Adelaide, and selling off the mission stock. At Christmas 1900 the Bama showed up in force for the farewell but Hörlein still had to stay on until May 1901.

Rev Schwarz at Cape Bedford had agreed to 'take on' Bloomfield on condition that Immanuel Synod would continue its subsidy even if the residents were removed to Cape Bedford. He finalised his marriage in May 1901 and then sent Rev Poland to Bloomfield. They claimed rations for 24 persons, but actually only two men and a woman and a few children were permanently at the mission, not enough to run a school. Rev. Poland supervised the dismantling of what was left of the mission to remove the building materials to Hope Valley. He tried to take the remaining residents to Cape Bedford, but most of them returned straight home.[25]

| 'Getting a drink at Bloomfield' |

| This must be after 1967 when a water supply was connected. Source: Box 34-65 7135, Lutheran Archives Australia |

Wujal-Wujal

Although the Bloomfield reserve was cancelled, the Kuku Yalanji remained in the area in several camps. Throughout World War II there was an indigenous settlement with a radio link to Cairns.

In 1957 the Hope Valley mission board was granted £2,500 to re-establish a reserve at the Bloomfield River, and 260 acres, including part of the old reserve, were gazetted in May 1958. It became a government settlement known as Wujal-Wujal, which is sometimes translated as ‘Many Falls’, and there certainly are some beautiful falls in the area, such as Roaring Meg. But it is an unlikely translation. Hörlein referred to the local language as ‘Wodjall’. According to John Haviland, wujilwujil means ‘hairy’ in the Kuku Yalanji language, and was used as a personal name.[26]

[1] Meston, Archibald Report on the Aboriginals of Queensland, 1896, Queensland Votes and Proceedings 1896.

[2] Grope, L. ‘Cedars in the Wilderness’ LutheranChurch of Australia Yearbook 1987, 25-57.

[3] ‘Petition of the settlers of Ayton and Bloomfield River to the Minister for Lands, November 1885’, in Grope, L., ‘Cedars in the Wilderness’ Lutheran Church of Australia Yearbook 1987, 25-57.

[4] Acting police magistrate W.O. Hodkinson, Report on Bloomfield, 1886, published in The Queenslander, 13 November 1886, cited in Grope, L., ‘Cedars in the Wilderness’ Lutheran Church of Australia Yearbook 1987, p. 32.

[5]8 December 1887 Meyer to Rechner, Bloomfield Mission Correspondence, 1887-89, Lutheran Archives Australia.

_thumb.gif)

.jpg)