Zion Hill Mission (1838-1848)

This was the first mission in what later became Queensland. It was intensively staffed yet surprisingly harmonious, and functioned to facilitate the settlement of Moreton Bay. Some of the Zion Hill missionaries themselves became pioneer farmers of the emerging state of Queensland, imprinting their names on the modern Brisbane map: Rode Road in Chermside and Wavell Heights, Zillman Water Holes, Zillmere, and Zillman Road in Hendra, Gerler Road in Hendra, Franz Road in Clayfield, Wagner Road in Clayfield, Nique Court at Redcliffe, Haussmann Courts and lanes in Meadowbrook (Loganlea) and Caboolture. They are remembered as the first free settlers of Queensland, producing the first free-born settler children in Queensland.

- Queensland's first Mission

- And we remember Zion

- Civilising Aborigines

- Mission impossible

- The Gossner Missionaries

- Recruitment and journey

- Johann Gottfried Wagner (1809-1893)

- Franz Joseph August Rode (1811-1903)

- Johann Leopold Zillmann (1813-1892)

- Johann Peter Niqué (1811-1903)

- Ambrosius Theophilus Wilhelm Hartenstein (1811-1861)

- Friedrich Theodor Franz (1814-1891)

- Carl Friedrich Gerler (-1894)

| The following missionary staff were associated with Zion Hill mission: Rev. Wilhelm Schmidt (leader) and wife Rev. Christopher Eipper with Harriet (nee Gyles) Peter Niquet (originally Niqué), mason, and Maria (nee Bachmann) August Rode (originally Rodé), cabinetmaker, with Julia (nee Peters) Leonard Zillmann, blacksmith, with Clara Gottfried Hausmann (later Godfrey Haussmann), farmer, with Wilhelmina (nee Lehmann) Wilhelm Hartenstein, weaver, and wife Carl Theodor Franz, tailor, and Maria (nee Weiss) Gottfried Wagner (later Godfrey), shoemaker, single Moritz Schneider, medical missionary (died in quarantine in Sydney, 1838) August Albrecht, shoemaker Ludwig Döge, gardener Carl Friedrich Gerler (arrived 1844) J.W. Gericke (arrived 1844) |

Queensland's first Mission

Queensland’s very first Christian mission was unusual in many ways. It was a combined Lutheran/Presbyterian/Pietist effort with Moravian inspiration. It was preceded by only three missions in Australia, at Wellington Valley behind the Blue Mountains (1821-1843), Lake Macquarie near the Newcastle convict colony (1826-1841) and Wybalenna on Flinders Island, in the convict colony of Tasmania (1835-1847). Unlike the Early Missions and Aboriginal Schools (at Parramatta, Port Lincoln and Perth), it was intensively staffed, more akin to Catholic mission initiatives than Protestant ones. That it was conducted by Germans was not unusual for the period.

Queensland’s very first Christian mission was unusual in many ways. It was a combined Lutheran/Presbyterian/Pietist effort with Moravian inspiration. It was preceded by only three missions in Australia, at Wellington Valley behind the Blue Mountains (1821-1843), Lake Macquarie near the Newcastle convict colony (1826-1841) and Wybalenna on Flinders Island, in the convict colony of Tasmania (1835-1847). Unlike the Early Missions and Aboriginal Schools (at Parramatta, Port Lincoln and Perth), it was intensively staffed, more akin to Catholic mission initiatives than Protestant ones. That it was conducted by Germans was not unusual for the period.

Zion Hill was part of a plan instigated by J.D. Lang to facilitate settlement in the Moreton Bay area. A notoriously brutal penal colony had been established there in 1824. By 1839 the convict settlement was wound down and the area prepared for civilian settlement, repeating the Port Jackson experience in Sydney. In 1842 the military was withdrawn and Moreton Bay was opened for free settlement. Government funding was withdrawn from the mission the following year.

| Map of selections and waterways at German Station, 1850s |

.jpg) |

| Zion Hill mission appears in the bottom left. Source: State Libary of Queensland |

The mission opened between April and June 1838, the result of joint efforts by Presbyterians, Lutherans and Pietists (from Basel and Berlin). It commenced with an unusually large number of staff for a Protestant mission – two ordained priests accompanied by ten laymen and eight spouses – a staff size ‘altogether unprecedented in the history of British Missions and British Colonisation’. With such an effort in staffing, this mission was clearly meant to succeed. However, it was not really considered a success in its time, and was finally disbanded in 1848 having witnessed the most difficult and destructive decade for the Aborigines of Moreton Bay.

The indigenous people of Moreton Bay were noted for having densely populated settlements and substantial dwellings. Their earliest European contacts were with absconding convicts and shipwrecks, all of whom concurred that the Aborigines had villages connected by well established paths, and that they inhabited substantial dwellings for a considerable part of the year. Such first-hand accounts, however, could not shake the expectations that newcomers brought with them, that they were encountering a nomadic and landless people.

Lang hoped to establish a string of missions along the dangerous northern coast in order to prevent attacks on shipwrecks such as had occurred in the cases of the Stirling Castle in 1836 near Fraser Island and the Charles Eaton in 1834 in Torres Strait. By placing this mission ‘five hundred miles to the northward of Sydney’ it was ‘supposed that the Aborigines of that distant portion of the colonial territory would be less contaminated by intercourse with the depraved convict population of the colony than those within the present limits of location’. That, at least, was how Lang described matters to potential financial backers in Britain.[3]

Frequent attacks by Aborigines at Redcliffe, though injuring no one, convinced the missionaries to move a little further out of range of the convict settlement, arguing that they “were desirous of establishing their station where they could come into contact with as many Aborigines as possible”.[4] The spearhead party had arrived in April, and by June 1838, when the remainder of their staff arrived in Moreton Bay they were already ensconced on a new site.

back to top

And we remember Zion

The New South Wales government reserved 650 acres of land for the mission at present day Nundah in Brisbane’s inner-Northern suburbs, just seven miles from the government station at Eagle Farm. The missionaries named their settlement Zion Hill - a biblical reference to the place of Christ’s return. Zion also symbolises holiness and a place from which ‘Christ’s Light’ shines forth. Such a compelling name makes the missionaries hopes clear. Samuel Smith’s poem, written in the wake of the early nineteenth century revival in global missionary work to encourage Protestant missions in the South Pacific, conjures Zion as a place from where the new world order emanates, as darkness gives way to light and the world is refashioned in a new dawn, a call to holy war. The imagery is powerful. The missionaries were inspired by seismic ideas of religious revivalism and a deep-felt sense of purpose, justice, and righteousness. They were ready to sacrifice themselves, if necessary, for this new world order. It was such a simple task, really: all that was required to dispel the darkness was to bring the light.

|

The Morning Light is Breaking The morning light is breaking, the darkness disappears; |

|

The creek which ran through the mission land was also replete with Biblical meaning. Now called Kedron Brook, it is believed to derived from a reference to Kidron Brook in the following passage describing King David’s flight from his rebellious son, " all the country wept with a loud voice, and all the people passed over: the king also himself passed over the brook Kidron .... toward the way of the wilderness." (2 Sam 15:23). This seasonal watercourse formed the eastern boundary of Jerusalem. To travel beyond it was to step into areas which worshipped other deities (wilderness). When it ran it carried much debris, and was dark. Its symbolic reference is to darkness, filth and cleansing.

back to top

Civilising Aborigines

Initial dealings with the Yaggera peoples (Jagera and Turrbal[5]) at this new location were quite favourable.[6] Through contact with the penal colony the Aborigines had learnt some English. The missionaries, who were still learning English tried to involve them in the construction of houses, as well as the very essential task of gardening, in an effort to develop a rapport with them. It was also an attempt to convince them of the ‘superiority of a settled life over a nomadic life’.[7] The mission journal, from which extracts were sent to the Sydney committee, refers to the presence of thirty Aborigines at the mission in July 1838 ‘some of whom were very diligent, and four spent the night at our place. They were much delighted when they saw Mr. Zillmann at the forge”. Ten adults and eight children attended the Sunday service, and on the following day one of them announced that ‘they would soon sing like us, and we hope earnestly that his may be the case.’ Soon the missionaries were ‘called upon by a black woman to make peace between her husband and some blacks with whom he was fighting’, and to dress wounds.[8]

Despite practical difficulties, Rev. Eipper conducted classes for Aborigines. In the attempt to teach, he learnt much about the Yaggera people, and acquired some of their language. The mission staff also performed outreach functions to contact indigenous peoples from the wider region. On these journeys they were looked after by local Aborigines.

back to top

Excerpts from the journal of the Reverend Christopher Eipper, Missionary to the Aborigines at Moreton Bay 1841 In August 1841 Wunkermany and the two brothers, Wogann, guided Eipper and Wagner to an initiation ceremony at Toorbul. Eipper’s journal gives some insight into the close relationships they were forming. Each of them was claimed as a brother by men from different areas, and there was much teasing going on, from both sides, although the pious brethren may not have fully appreciated the extent of Aboriginal humour. More.

Eipper’s journals of two journeys, in August 1841 and November 1842, give great insight into the lifestyle of Moreton Bay Aborigines. It details their abundance of food, their large dwellings and well defined paths. The 1842 journal starts to also give an inkling of the encroachment of settlers on Aboriginal land. This journal describes the destruction of the Duke of York native camp by two soldiers who were refused access to Aboriginal women.

The indigenous people of York’s Hollow were finally displaced with the arrival of Lang-initiated migrants in January 1849. Some 550 pious Protestant dissenters arrived on the Fortitude, Chaseley and Lima during that year, finding that their land orders were not underwritten by the government, and ‘armed to the teeth’ took up temporary encampment at York’s Hollow, later called Fortitude Valley.[10]

| Journal of the Brethren Eipper and Hartenstein, who resided among the natives on the Pine River from Nov 4-11 1842[11] The native Wunkermany with two women having offered themselves as bearers of provisions to Umpie Bong, we set out this morning for that place. More. |

.jpg) |

|

Sketch of Zion Hill Mission produced by Missionary Gerler in 1846.

Source: http://enc.slq.qld.gov.au/

|

At Zion Hill, Gerler portrayed life at the mission in a drawing that suggests that the colonists quickly developed a deep sense of place, of presence and of accomplishment. Gerler arrived at Zion Hill in 1844, and dated this drawing as 1846.

It shows Aboriginal children being taught by the white teacher and Aborigines working in the fields using European farming implements. The cattle, the well-ploughed fields, the peach trees in front of the houses, the straight lines of crops of corn and sweet potato, all demonstrate how the missionaries brought ‘civilisation’ to the indigenous inhabitants, how they brought the stamp of the European world to the new country.[13]

German explorer Ludwig Leichardt visited Zion Hill in 1843 and reported favourably, responding to detrimental comments about the failure of the mission:

The missionaries have converted no black-fellows to Christianity; but they have commenced a friendly intercourse with these savage children of the bush, and they have shewn to them the white fellow in his best colour. They did not take their wives; they did not take bloody revenge when the black fellow came to rob their garden. They were always kind, perhaps too kind.[14]

The mission may have failed to bring Christianity to the Aborigines, but it absolutely succeeded in transplanting a piece of Europe to Australia. Perhaps that was all that was required of it. In 1843, shortly after opening the area to free settlement, the New South Wales government withdrew its funding for the mission.

back to top

Mission impossible

|

|

Last remaining building from Zion Hill Mission, photograhed in 1895 Source: http://enc.slq.qld.gov.au/ |

The missionaries were hampered by two central problems, the lack of appropriate funding on the one hand, and the disinterest of the Yaggera people in European civilisation on the other hand. The original appeal to the British authorities in setting up the Zion Hill mission assumed that it would be self-sustaining (‘along Moravian lines’). This posed a major problem to the missionaries who had to work very hard to make their settlement self-sustaining, leaving little time for missionary work. They had transplanted themselves from Germany into an unfamiliar natural and social environment. Setting up a viable economic presence became the primary battle to which they devoted most of their energies.

The missionaries believed that they would not be successful unless they could have regular contact with the Aborigines, but they also realised that the Aborigines’ interest in them was quite sporadic - the Yaggera would only come if the missionaries were willing to share food and tobacco.[15] Too often the missionaries did not have enough food for themselves, and sometimes had to resort to pushing a wheelbarrow down to the penal colony to beg for food, as the minimal government funding did not go far.[16] Moreover, when the ‘church bell’ (actually a tin drum) was rung for prayers, the Yaggera knew quite well that no one would be there to guard the gardens, and would often make raids on the food supply, until some of the missionaries resorted to shooting their guns to scare them off, which led to an inquiry from the Moreton Bay commandant, and an explanation sent to Lang.[17]

Under these pressures, the once optimistic missionaries soon became frustrated – not with a government which had given them an impossible task - but with the Aborigines. Rev. Eipper initially said “the intellectual faculties of the Aborigines are by no means to be despised”, but within a short while he saw them as “the living embodiment of Philippians 3:19 –Whose end is destruction, whose God is their belly, and whose glory is in their shame, who mind earthly things.”[18] Eipper observed that almost all the Aboriginal children were to some degree affected by syphilis (contracted from contact with the penal settlement), but interpreted the widespread venereal diseases as ‘a judgement upon the Aborigines’.[19]

The Yaggera people’s initial curiosity about the new settlers, which prompted attendance at services where they listened to long sermons and lectures, must have eventually been sated. Eventually they gently reminded the missionaries that they had already heard it all before, although missionary zeal may have prevented their instructors from understanding the message. Haussmann recalled enthusiastically in 1855:

They do retain in their language what they have heard of God. Some of them said to me on the last journey when I spoke to them of God, they replied, they knew all about God still because I had spoken to them about God some years ago and they have not yet forgotten it.[20]

Public interest in the mission also waned. Despite evident efforts by the Sydney committee to raise funds, some of the donations appear pitiful, such as:

Subscribed by the Children attending Mr Steel’s Infant Training School Pitt Street during the year 1841 for the Moreton Bay Mission, £1.10.[21]

That year public subscriptions hit a low point. In its first year the mission committee was able to raise £310, which dropped to £159 in 1839, recovered at £228 in 1840 and fell to £93 in 1841.

The Sydney committee was re-organised in March 1842 along more interdenominational lines. It now included Lang for the Presbyterians, John Saunders for the Baptists, merchant David Jones, and Rev. Dr. Robert Ross of Sydney for the Congregationalist, and as well as a number of others.[22] Despite this reorganisation, the committee withdrew its financial support in October 1843, whereupon the colonial government, which had undertaken to match public contributions to the mission pound for pound, also withdrew its funding.

New South Wales Governor Gipps, who visited the mission in 1842, had already indicated that in order to receive continued funding, the mission needed to find a new site further away from Brisbane. Presumably it was taking up too much valuable land in the newly opened settlement zone. Revs Schmidt and Eipper therefore toured the Bunya Mountains and Wide Bay area again, gathering evidence that beyond the limit of authorized settlement squatters were poisoning Aborigines. They reported to the Sydney mission committee in July and September 1843, but instead of approving a move to a new site, the committee decided to abandon the mission.

Rev Schmidt became incensed and disillusioned by the ‘shameful, treacherous, backsliding work’ of their supposed supporters in Berlin and Sydney.[23] But the lay missionaries optimistically argued that they could possibly support the mission themselves through manual work – a sensible suggestion since they had ploughed all their energies into that piece of land for the last five years and their last subsidy was £186 for the twenty of them with eleven children.

Whether because of their self-confessed ‘lack of progress with the Aborigines’, or because of a sense of ‘mission accomplished’ with the transition from a penal to a free settlement, the government ceased funding the mission in 1843.

The British government had assured to match funding, but this funding actually came from the sale of crown land and therefore from the colonial budget. J.D. Lang recollects the end of the mission as follows:

All the Aboriginal missions of that period having proved unsuccessful, Sir George Gipps, the Governor, determined at length, with the sanction of Lord Stanley, who was then Secretary of State for the Colonies, and who declared that he gave that sanction with the greatest reluctance, to withdraw the Government support, which had been equal to the whole contributions of the public in each case, from all the missions, and to leave the Aborigines to their fate. The mission at Moreton Bay was accordingly broken up.[24]

However, Lang did have a way of putting things. ‘All the missions’ at that time actually meant only two that were supported by the NSW government, and both were at that time conducted by Germans: Zion Hill and Wellington Valley.

The opening of Brisbane to other free settlers clearly caused jealousies about the large allotment of land to the mission. A settler complained in the Moreton Bay Courier, (27th June 1846) that the missionaries, freely given ample fertile land, had done a very poor job of converting Aborigines, but had done an excellent job of growing vegetables.[25]

It took another fifteen years before the new state of Queensland passed its own immigration laws in 1861, granting each new male or female self-financed immigrant 18 acres of free land. Even compared with that, the initial grant of 650 acres to the Zion Hill missionaries (20 adults and 11 children) appears generous, if it is considered a grant made to the missionaries (whose passages had been financed). But if it was land reserved for the indigenous owners, it appears stingy.

Despite this pressure to close the mission, two new artisans,Gerler and Gericke, were sent from the Gossner institution to reinforce it in January 1844, when Rev. Eipper and Wagner left, the two who had clearly good relationships into Aboriginal families. Since there were few Aborigines left at Zion Hill and the government pressured the mission to move, Hausmann and Hartenstein now tried to set up a branch station at Burpengary (Deception Bay). However they were attacked by Aborigines, and Hausmann severely wounded, a leg injury that was to trouble him for the rest of his life.

Rev. Schmidt left the mission in 1845, but 5 lay – helpers stayed on until 1848, when they ended their active attempts to convert the indigenous inhabitants and a number of them became the nucleus of a lasting German farming community.[26] The government subdivided the land and sold it back to them in parcels as small as 5 acres. Nearly twenty years later one of them, Hausmann, and his son recommenced a mission at Bethesda: ‘We begin again where we ceased years ago.[27]Hausmann wrote to Lang in July 1855 affirming that it was possible to Christianise Aborigines:

I never could give the natives up … I ask, has ever the Gospel, that is, the whole Gospel been fully preached to them in their own language? I believe not.[28] More.

What had been the intentions of these missionaries? Did they succeed or fail? Were they to both Christianise and salvage the Yaggera, and to settle and subdue the people and the land ready for settlement? Did they fulfil the Gossner mission, or that of the government?

back to top

The Gossner Missionaries

Most of the missionaries who arrived in Moreton Bay in 1838 were trained in Berlin under Pastor J. E. Gossner from the more evangelical and less dogmatic branch of the Protestant church in Prussia. This is what facilitated the Gossner relationship with English Protestants, but was also to lead to rifts with more dogmatic German Lutherans. The Gossner men were drawn from a variety of social, regional and confessional backgrounds, but united (like those from Basel) by a strong pietism bordering on asceticism and a sense of calling to bring the gospel to the heathen world in order to assure its salvation. The Gossner Mission has always been supra-denominational.

The missionaries who established Zion Hill were mostly in their twenties: young, energetic, optimistic and driven with purpose. They were entering into other nations’ colonies: they did not battle for a king or a Kaiser, not for a country or an empire, but for a greater, higher, more glorious and more important purpose, for which they were ready to face primitive conditions and physical hardships. They were indeed, ready to die for their conviction: they were ready to never return home.

Their conviction was only matched by their humility. They knew that they could not understand the people whom they were supposed to meet, educate, elevate, civilize and save. They knew that they could not be sure of their reception. The only certainty they had was this: that they were doing the right thing. They were doing the good thing, the only truly worthwhile thing, to spread the word of God. There was only one other certainty besides this: that if they faltered from this belief, they were doomed, and damned, and lost.

back to top

Recruitment and journey

J. D. Lang began to take an interest in the Moreton Bay Aborigines around 1831, and initially sought to recruit Scottish Presbyterian missionaries. During a visit in Europe he encountered a banker who enquired about the prospects for a German contingent of missionaries to be sent to Australia, an inquiry presumably emanating from the new Gossner Mission institute in Berlin seeking placements for its first batch of graduands. The British government contributed £450, and Lang’s brother Andrew contributed £150, only enough funds to support the journey of four missionaries at the current rate. Lang then apparently borrowed some more money (he mentioned in October 1839 that there was still a debt of £350 remaining from the establishment cost) and eventually managed to arrange the journey of twenty adults. As far as the Gossner Mission chronicle is concerned, it sent 12 adults from Berlin to Australia on 9 July 1837 which is the date when they were designated at the Bethlehem Church (this figure probably excludes all wives, and includes Eipper and Schneider).[29]

The group consisting of Rev. Schmidt nine leading artisans and their wives sailed from Germany in September 1837 to Scotland, where they were joined by Rev. and Harriet Eipper and a medically trained member of the Basel mission society, whom Lang had recruited separately, Moritz Schneider, and his wife Maria. They arrived in Sydney on the Minerva in January 1838, but were kept in quarantine until April, as typhoid had developed on the ship. While in quarantine typhoid claimed the life of Moritz Schneider, who had been attending to the sick, replacing the ship’s surgeon who had also contracted the disease. Finally the schooner Isabella took the first party of 15 mission members up to the Moreton Bay penal colony, the remainder, including Rev. Schmidt, joined them in June at Zion Hill.[30]

The new arrivals were assisted in learning the Turrbal language by Rev J.C.S. Handt who had arrived from Wellington Valley the year before. A number of them anglicized their names in order to more easily assimilate into the English-speaking society, so that there are two correct ways of spelling their names. None of the arrangements for their departure mention any children, and neither do their Sydney shipping records in 1838, but Eipper’s report in 1841 refers to eleven children, of which three were Rode’s.[31] Eipper himself, married only in 1847, had two children by this time. The Zion Hill women were clearly busy, and produced the first children of free settlers in Queensland. J.D. Lang’s idea that the mission was to be set up ‘along Moravian lines’ evidently included the Moravian tradition of arranged marriages, although Lang was actually alluding to the Moravian model of sending unpaid colonists as evangelists.

By bringing their wives with them, and quickly producing families, the mission staff formed an incredibly stable community. Remarkably, none of the mission staff abandoned the mission, until after funding had been withdrawn, when the Eippers and Wagner became the first to leave in 1844. Schneider’s widow Maria remained with the group and married Karl Franz the tailor, and J.D. Lang obtained funding to replace Moritz Schneider with another medically trained recruit from the Berlin Mission institute, Rev. Rudolph Krause, newly ordained by Dr. Steinkopf, an influential German Lutheran in London. Both the arrival of Krause, and the fate of two unmarried colonists who were in the party leaving from Berlin, August Albrecht (b. 1816) and Ludwig Döge is obscure. Lang merely mentions in a footnote that ‘having been guilty of an offence which could not be overlooked, they were excluded from the mission’.[32] The only bachelors remaining among the mission staff were Wagner, and possibly Krause, about whom little is known, until the arrival of Gerler and Gericke.

Eipper and Schmidt took turns in performing Sunday services and twice daily morning and evening services, ‘by singing God’s praise, reading His word, and calling upon His name; every one that feels disposed being likewise at liberty to engage in prayer’. This may refer to the presence of Aborigines at services, but it may also express the pietist conduct of services involving the parishioners in its performance. It appears that only Eipper was fluent in English.

It is also sincerely hoped that we soon shall be able to make use of the English language in this worship, which is already the case with the daily service in the morning in the morning, conducted by myself – save the singing – the daily evening service cannot but be held, at present, in the German language, as each of the brethren is taking his turn.

They also held monthly prayer meetings and a weekly community conference:

Where the manner of our proceeding in particular should be treated, existing differences be adjusted in brotherly love, and where the brethren in general should exhort each other, and be renewed in their faith and love and hope, to strengthen each other’s hearts and hands in this glorious work.[33]

The cohesion of this small community is all the more remarkable since they were drawn from a range of confessional backgrounds which caused deep rifts in practically all other German Lutheran communities in South Australia, Queensland and Victoria. Some of them, like Zillmann, were from the Prussian (Evangelical Lutheran Church), others like Gerler and Gericke were old-Lutherans, Schmidt was thoroughly supra-confessional, and Eipper was trained in Basel by pietists.[34]

That the colonists of Zion Hill were very pious is beyond doubt. After the demise of their mission five of the eight laymen underwent further training and were themselves ordained.

Of these, Hausmann himself went on to ordain a number of laymen who had assisted him in the attempt at a mission at Nerang Creek. The ordination of laymen after a brief period of instruction was not uncontroversial. In 1864 an anonymous letter appeared in the Queensland Daily Guardian, signed ‘Anti-Humbug’, calling for a government investigation

to find out what claim the German clergymen in Brisbane really have to that important position – whether they were brought up in the ministry, or whether it suited them … to enjoy all the emoluments and respects paid to that position, instead of carrying on the handicraft to which they had been trained at home in Germany, for I understand that none of them … came near a University. …. (one of them is a Presbyterian clergyman) who has been nothing more than a cobbler in Germany, and who was sent out with other handicrafts men and two missionaries to teach the blacks his noble craft.[35]

The ‘cobbler’ was a reference to Wagner, but the allegation that they enjoyed ‘emoluments’ was ill-informed, because Queensland had abolished ministers’ stipends with the State Aid Discontinuance Act (1860).

One author surmises that they all came from large European cities and were therefore unused to the heat and dust of the Australian landscape.[36] This is far from true. The Gossner mission trained primarily sturdy artisans who were drawn largely from rural regions. Wagner and Rode were from Silesia, Nique was the son of farmer in Brandenburg , Franz was from Pomerania, Zillmann from a village near Frankfurt on the Oder. Nor were they immersed in an intemperate or dusty region of Australia, like some of their South Australian brethren.

Of the staff associated with Zion Hill Mission, the two who were sent as ordained missionaries, Wilhelm Schmidt (see separate entry) and Christopher Eipper (see separate entry), left the area. Eipper, who was from southern Germany and trained at Basel, left in 1844 to become a Presbyterian minister in NSW, whereas Schmidt left in 1845, and later joined the LMS (London Missionary Society) mission in Samoa.

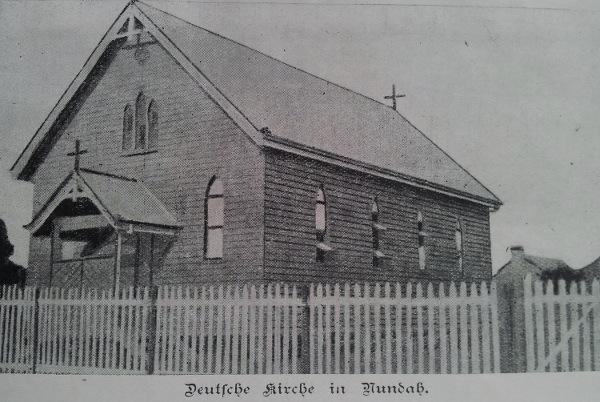

However the laymen formed a strikingly cohesive group. Five of them went on to be ordained: Wagner, Nique, Gerler and Gericke, and Gottfried Hausmann, who became one of the few in Queensland who sought to continue a heathen mission during a period of general apathy. Six of them settled in the Nundah area (Wagner, Rode, Zillmann, Franz, Hartenstein and Gerler) while Hausmann settled at Beenleigh and Gericke eventually returned to Gympie in 1867. He was ordained in 1853 together with Nique and both ministered to Germans on Victorian goldfields at Bendigo, where Nique remained. Little is known about the shoemaker August Albrecht and the gardener Ludwig Döge who both arrived with the group in 1838, but on the whole the high life expectancy of this group is striking.

back to top

Johann Gottfried Wagner (1809-1893)

Godfrey (originally Gottfried) Wagner was one of the few bachelors at the mission and was among the first Zion Hill staff to leave in 1844, but later returned to German Station as an ordained priest. The son of a shoemaker in Glauchschutz, Silesia (Prussia), he was a shoemaker by trade, and attended the Gossner Mission institute in Berlin, to join its first sending out of missionaries. He was 28 when he arrived in Australia. After six years at Zion Hill became a cathechist in southern New South Wales and entered into J.D. Lang’s Australian College established in 1850. In February 1850 he married Anna Weiss, and in October of the same year he was ordained by the Presbyterian synod and stationed at Tumut, before returning to Nundah out of consideration for his wife’s health. In March 1863 they auctioned three lots in the parish of Toombul, county of Stanley, totalling 93 acres for £445 and started a farm in the area then known as German Station.

According to local memory, Wagner became the first to grow pineapples in Queensland on a commercial basis, which later became a substantial agricultural activity in Queensland. The plants had been introduced from India by Rev. Handt who propagated the pineapple plants on a site near the existing Treasury buildings around 1838. (There had been earlier acclimatisation experiments in Sydney.) A few years later he gave them to Wagner at the German mission at Nundah, from where they were distributed among neighbouring settlers.

Wagner went on to establish a dairy, in addition to being a minister to the local community at German Station. In 1856 he was appointed as an itinerant minister in the Burnett and Darling Downs district. He had five children and lived to age 84.[37]

back to top

Franz Joseph August Rode (1811-1903)

|

|

Franz Joseph August Rode (1811-1903) Source: http://enc.slq.qld.gov.au/ |

Franz Joseph August Rode (or Auguste Rodé) was a joiner and cabinetmaker when he joined the Gossner mission institute to become a lay missionary. He was the son of a musician in Siegert (Silesia, Prussia). He married Julia Emilia Peters (b.1815) from Hatzel in Brandenburg, who accompanied him on the Minerva to Moreton Bay. By 1841 they had three children. Rode played an active part in building the Zion Hill mission as well as establishing crops to sustain its community.

After the mission folded Rode stayed on and purchased land in the area. At an auction in March 1863 he successfully bid, next to Wagner and Franz, for 32 acres. He established a house which in time was sold on to the Catholic archdiocese of Brisbane to be used as a convent and school. He gave evidence, along with Zillmann, to the 1861 inquiry into the native police in Queensland, arguing that the mission would have been successful if funding had not been withdrawn.[38] He lived to age 92.

Johann Leopold Zillmann (1813-1892)

Leopold Zillmann was from Neu-Ulm in Prussia, where he was baptised and confirmed in the Evangelical Lutheran Church. He was a blacksmith when he entered the Gossner Mission. He arrived at Moreton Bay with his wife Clara (b. 1817), a Berlin schoolmistress. By 1841 they had two children, one of them was the second child born in Queensland to a free settler. This family also stayed on at German Station after the mission was wound down. Zillmann purchased land near Zion Hill and became a farmer while still being actively involved in the Lutheran, Methodist and Baptist churches in the local area.[39] He and Franz became pioneers of the Caboolture area, and like Rode, gave evidence at the 1861 inquiry into the native police, proposing the establishment of a missionary cotton plantation. He had been writing to Gossner and the German migration agent Heussler about this. This proposal became the only recommendation made by the inquiry, and was ignored.[40] Unlike most of his Zion Hill brethren, Zillmann did not quite reach the age of 80.

Johann Peter Niqué (1811-1903)

| Pastor Niquet |

.jpg) |

|

Photo taken at 'Berlin Studio' in Australia, possibly just after his ordination in 1856. Source: Mounted Photograph Collection, Box 6, Lutheran Archives Australia |

Peter Niquet, also one of the original Gossner men at Zion Hill, was a bricklayer by trade and must have been very useful in the building of the mission. He was the son of farmer from Ropin in Brandenburg, and his wife Maria nee Bachmann (b. 1815) was from Saxony. He was ordained in the synod of New South Wales in November 1856 together with Gericke. Presumably they had both attended Lang’s Australian College. He was called to the Lutheran congregations on the Victorian goldfields where he served at Ballarat, Light’s Pass and Adelaide. He died in Bendigo at age 92.

Ambrosius Theophilus Wilhelm Hartenstein (1811-1861)

Little reference is made to Hartenstein. He was a weaver when he entered the Gossner mission, and arrived at Zion Hill with his wife. He appears to have been a good bushman, since he accompanied excursions by Eipper attempting to find a new location for a mission, by Gerler who left him in the bush with a bogged horse, and by Haussman, who was injured during an Aboriginal attack at Burpengary. He died at age 50.

Friedrich Theodor Franz (1814-1891)

Also referred to as Karl or Charles Theodor Franz, and as Frederick Theodore Franz, a tailor by trade, he was a Gossner graduate from Pomerania. He embarked on the journey to Zion Hill as a bachelor, but married Maria nee Weiss (b.1811), the widow of Moritz Schneider. By 1841 they had two children. At public auction in March 1863 they acquired 25 acres and remained as settlers at Nundah. Franz died at age 77.

Carl Friedrich Gerler (-1894)