Handt, Johann Christian Simon (1793-1863)

Prepared by:

Regina Ganter

Reverend Handt was the first Basel candidate in Australia, and the first missionary in Queensland. He became a victim of the wrangle between the Anglican state church and other Protestant denominations. He had three years’ missionary experience in West Africa before coming to New South Wales in 1831, and worked at Wellington Valley mission (1832-36), Moreton Bay convict settlement (1837-43), as a teacher at Lindfield near Sydney (1842-1854) and as prison chaplain at Geelong (1854-1863).

Table of Contents

Europe to Africa

Johann Christian Simon Hundt was born in Aken on the Elbe River, near Dessau, Germany. Because ‘hund’ means ‘dog, and he was teased about his name, he changed it to Handt. He was a 29-year old tailor when he made his application to Basel Mission institution. Writing from St. Petersburg, his eight-page resume reveals that his mother died when he was 19 and his father when he was 22. He had an older brother in Berlin. He completed six months military service, and then spent a year in Rostock, later moved to Lübeck, then Riga, and finally to St. Petersburg where he met Johannes Gossner who supported his application to the Basel Mission institution. He belonged to the Reformed Church and trained at the Basel Mission from November 1822 to 1827. He was enrolled as its 58th candidate.

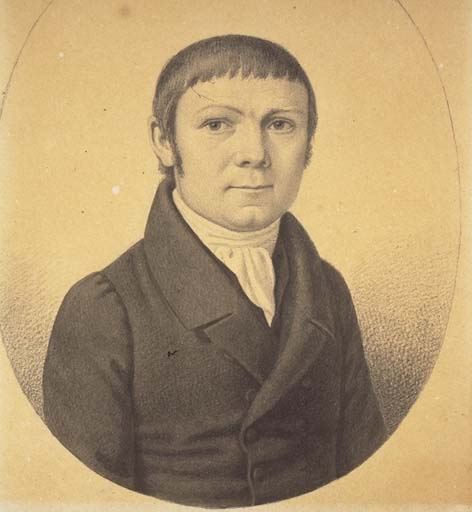

| Johann Christian Simon Handt, 1827 |

|

| Source: Basel Mission QS-30.001.0054.01 |

Handt was ordained at Auggen in May 1827 and posted to Liberia (Sierra Leone, West Africa) in May 1827, departing from Monrovia in December 1827. During his three years in Liberia some tension arose with one of the Brothers posted with him, and the mission was plagued by illness. Handt took it upon himself to move into the African interior and set up at Cape Mount, but periods of illness prompted a request for a different posting. When the CMS (Church Mission Society) did not respond he travelled to England in October 1830, much to the embarrassment of the Basel Mission Society, which now felt obliged to reimburse the CMS for his passage to Africa.

Sydney

Handt was allocated to a penal transport to New South Wales on the Eleanor, in order to set up a new mission at Wellington Valley near Mudgee with Brother Watson. On board from April 1831, he ministered to the convicts, soldiers and sailors, and gave German lessons to one of the officers, improving his English in return. The Eleanor arrived in Sydney in September 1831.

In Sydney Handt stepped into an emerging contest by the Anglican Church in Australia to bring heathen missions under its umbrella. The Wesleyans had initiated Wellington Valley mission at the expanding frontier eight years earlier but abandoned it. This was now to be reactivated, but Archdeacon Broughton was put out because the British government had not placed him in charge of the mission. The Reverend Marsden summarized his own feelings towards Aboriginal missions, declaring ‘Much money has been thrown away upon them.’[1]

Handt continued to hope that he could work together with Brother Matthews from the CMS College at Islington, but Matthews was sent to New Zealand as originally intended. Handt now awaited the arrival of Brother Watson, whose departure had been delayed for nine months due to difficulties with his ordination. During this time Handt ministered to convicts and asylum inmates around Sydney. Handt was still not married, and by April 1832 wrote despairingly about the poor prospects in such a convict colony.

The Rev. William Watson and his wife Anne (nee Oliver) finally arrived in May 1832, and in July Handt married ‘Miss Crook’, daughter of a missionary, who had been in the South Pacific since age 11. ‘I hope she will be a useful addition to our mission’, wrote Handt, omitting to mention her name, Mary.

To Wellington Valley

Handt trekked to Wellington Valley and noticed the effects of the 1830 – 1831 smallpox epidemic which had ravaged the Aboriginal people of New South Wales. Along the journey he endeavoured to recruit Aborigines for the new mission. Some, from Marsden’s station at Molong accompanied them, but elsewhere white owners had warned their Aboriginal workforce that the missionaries were going to take their children away to jail.

They made slow progress on the trek and were frequently invited to visit stations along the way, including one belonging to Rev. William Lane. The major difficulty they encountered was the loss of bullocks. The convicts and Aborigines assigned to accompany the missionaries seemed to lose track of the bullocks or horses almost every night, so that the mornings were spent looking for them, instead of setting off. The bullocks were generally found on a Saturday afternoon, but of course the missionaries would not countenance travelling on a Sunday. ‘There never has been such a year as this for losing bullocks’, observed one of the crew. The climate also proved difficult. In Sydney Handt had been enthusiastic about the mild climate, but as they moved into the interior they were to labour under temperature as fierce as 42° in the shade.

Frontier society and Aboriginal expectations

Handt’s arrival at Wellington Valley in October 1832 coincided with the withdrawal of the government from the convict farm there. Consequently, they occupied some disused government buildings, including a commodious ‘government house’ at the top of the hill. They were guarded by a military detachment, and in turn they had to supply the military staff with food.

Aboriginal people in the area already had various interactions with white settlers, convict workers and military, and were able to express themselves in frontier English. This was sometimes misunderstood by the newcomers to be Aboriginal, such as when Handt asked one of the Aborigines what he thought had made him sick, and understood the ‘wong-ding’ in reply to be a reference to the devil.

The missionaries’ journals paint an abysmal, gut-wrenching, image of the frontier society. Aboriginal children were being ‘procured’, sometimes for money, among the settlers, and there are frequent references to Aboriginal girls around the age of eight being used by white stockmen as female companions. Older Aboriginal men were lending their younger wives to various stations in order to be able to draw on rations and supplies. They saw no distinction between missionaries and settlers, all were treated as local ‘bosses’ who made various demands in return for food.

Aboriginal people who left children at the mission for a period felt entitled in return to draw on the mission rations, whether or not they worked as required in cutting bark and other jobs the missionaries demanded of them, often promising to do so ‘tomorrow’. They even cited the prayers to remind the missionaries of these reciprocal obligations: ‘give us this day, all day, our daily bread: and forgive

us our trespasses’.[2]

When the government blankets arrived, Aboriginal people would turn up in large groups demanding to have them distributed, arguing that the government was sending these blankets for them, not for the missionaries. This presented a quandary, since in the first year 40 blankets arrived, in the second year 60, and the first group to arrive consisted of 30 people. Clearly there were not enough blankets to go around for a year, and some were always needed at the mission for the care of the sick and the children. Watson cut the blankets in half.

Aboriginal people understood the missionaries as local bosses who needed to be mindful of the government, and indeed they acted very much like local bosses. They often paid for the girls they obtained with perhaps a handkerchief or a necklace. They missed no opportunity to ask for children, and gradually gathered the sick, blind and lame girls, but always had a good supply of young boys at the station. The boys, however, were not quite clear what their role was, and asked ‘why do you talk so much to us about these things?’ (meaning God, death and afterlife).[3] Most did not stay very long, and generally left after their ceremonial initiation into manhood.

Watson habitually quizzed people on the afterlife, to determine how much they knew about God and the world. If to the question ‘what will happen to you after you die’, they replied ‘nothing’, then they clearly had either not been exposed to or not understood the gospel. This kind of talk about dying was often resented: ‘What for you speak much about God and devil and dying. No other white fellow no other master talk that way.’[4] Handt, too, was told straight out by some other adults that they didn’t want to constantly hear about death and afterlife.

Aboriginal people were resentful that the missionaries tried to gather up girls (‘yeener’, girls of marriageable age). Handt described one such debate with an Aboriginal elder:

‘what for want you females to sit down with you?’ I told him that we might teach them to read the holy Book; and to know God and the way to heaven, he answered ‘well, that very good for boys, no good, no good at all for girls, but I am very hungry and must have some Flour and Beef and Tea and Sugar and Tobacco, I must have now I want to go to camp.’[5]

Aborigines thought it much preferable if the mission confined itself to housing young boys. They also threatened to invoke police protection if the missionaries persisted in gathering up children and young people: ‘No good Parson get pikininny, get yeener, get young man all about. What for not all about go in bush. Governor come up by & by take up Parson, put him in jail’.[6]

The girls at the mission were in danger of abuse by convict workers, visiting whites who came for medical treatment, and young Aboriginal men. They were locked up at night and often tried to abscond. In February 1834 Watson described how on one of his journeys around the Aboriginal camps he caught up with a blind girl. The missionaries had ‘purchased’ her for a blanket, but she had been picked up again by her mother. On noticing the missionary, the girl ‘ran away with all possible speed’ and was ‘very much afraid’. The parents were ‘unwilling to let the child go’ and ‘the mother of the girl was determined to go with us. I used my utmost endeavours to dissuade her but all to no purpose’. For the first seven nights the girls purchased on this journey were locked up in Watson’s study, until he had fixed an extra shutter on the window of the outside hut. ‘But they had not been in it half an hour before the blind girl had climbed up through a small hole which had been left to admit light into the hut.’ She was caught, however. ‘It is not to be understood that we keep them as prisoners night and day. During the day they have sufficient liberty but at night we are anxious to have them where there is neither ingress nor egress for several reasons.’ [7]

Infanticide

The missionary journals make some reference to the infanticide of new-born mixed-descent children, which appear entirely convincing, but may yet arise from misunderstanding and misinterpretation. In February 1834 Watson observed that ‘it is a custom to hold their infants in smoke for a considerable time and to rub them over with the bark of a certain tree which is exceedingly Black’, and that this may be the cause of the blisters he observed on the hands and feet of a sick two-week old baby.

A year earlier, unaware of this custom, he had described what appeared to him to be an attempted infanticide. The case referred to one of the two wives of Woowah (Blind Bobby), an older Aboriginal man who often camped near the mission. The young woman had denied being pregnant two days earlier, and one evening the two women were missing from the camp, having retreated to the bush on the pretext that the baby Charlotte was crying too much. Watson and his wife were suspicious and got two of the girls to lead them to the spot where the women were.

When we had come near to the place we perceived by the light of the fire a white infant laid very near to it, and apparently struggling in the agonies of death but not crying. The elder yeener was sitting with her back to it, and the younger yeener was digging a hole in the ground with a long stick (which they use for the purpose of digging up roots &c). Mrs W asked her why she had killed the child? She said no good that one, this one very good, taking the Black child Charlotte and putting it to her breast. Mrs W asked her if she killed the child with the staff? She said no, with her foot. Mrs W took the babe and wrapped it in a blanket which she took from one of the girls, and folded it in her cloak for it is a very severely frosty night. The babe felt the warmth and feebly cried, on which the cruel mother seemed surprised, and looking round said, ‘you give it me now, you have it in morning’. Having bought it home Mrs W prepared some cordial and took it to the wretched parent who is about 1/2 a mile from our house. When she returned and began to wash the babe, it was found to be literally covered with dirt and its back much burnt. When the yeener was asked why she had denied being pregnant she replied that she was afraid.

Sunday 28th.

Mrs W had prepared some cordial to take to the yeener this morning, but she was up at this place early. She asked Mrs W if the child cried very much, the ans'r was no. She then said ‘don't you let Black fellows make light, my Black fellow is blind, he cannot see that it is white’. A short time afterwards she came into the house when Mrs W was dressing the babe. She said well, you may have it, I don't want it. The poor little creature has caught a very severe cold.[8]

The episode sounds as if the young mother had tried to blacken the baby with smoke, was much concerned because it was white, and resigned herself to having to give it away.

The trials of bush life

Handt’s diary is somewhat less colourful than Watson’s regarding his interaction with indigenous people. He had trouble with Aboriginal and English names, so that his journal has generic entries referring to ‘this boy’ and ‘that boy’ for years, whereas Watson’s journal refers to most of the Aborigines either by a Christianised name or a transliteration of an indigenous name.

But Handt relates an episode where he traveling through the bush, wearing an opossum cloak as usual, and accompanied by an assigned convict. A bushranger held them up demanding his money and weapons. The bushranger was incredulous when he found that Handt had neither, and then quizzed the assigned convict whether Handt was treating him decently. The convict had no complaints, and the bushranger, having run out of options to either rob or punish Handt, contended himself with some bread, sugar and a handkerchief. He let them go before Handt could launch fully into his missionary speech.

He often scolded Aboriginal people for hunting or fighting on a Sunday, or swearing at a dog, or swearing at all. He did not appear convinced that he was making an impact, noting much resistance to his gospel (‘what you said about God is not true’, ‘you’re telling stories’). On the whole however, there was an increasing curiosity among Aboriginal people about this God, who made everything, including all the commodities that the missionaries had (‘the pipe, too?’), and who also loved them, so that presumably some of the things he had made must be destined for them, as well.

His wife’s second confinement appeared to trouble Handt greatly. In mid-July 1834 he hurried to the nearest doctor at Murrumburgeri, 22 miles away, but the man refused to accompany him back to the mission, asking to send word when the date was closer. Handt then sent to Bathurst for a ‘government woman’. The baby daughter was delivered three weeks later, on 13 August, leaving a 23-day gap in his diary entries.

It was her third confinement that nearly claimed Mary’s life. Handt wrote that she had so much trouble that she took leave of them three times, thinking she was going to die, her illness developing into utter mental confusion (‘vollkommenen Wahnsinn’). According to Watson, Handt delivered the baby boy himself, despite some women being present. In April 1836 the Handts set off to Sydney to obtain better medical treatment, leaving one of their children in the care of Mrs Watson. Watson expressed surprise when Handt returned in July 1836 to announce that his transfer to Moreton Bay had been arranged[9]

Friction between Handt and Watson

There is very little reference in the missionaries’ journals to each other. The journals were sent as quarterly accounts of their activities to the committee in Sydney, and the Brothers signed off on each other’s journals. They were therefore not likely to raise overt criticism of each other in these journals. While Handt’s journal reflects his limited confidence in the success of the mission, Watson detailed the ‘evils’ they were labouring against. The journals give the impression that they were acting in isolation from each other. Both conducted work amongst the Wiradjuri, but separately, using different phonetic conventions. It later transpired that they were barely on speaking terms.

Watson was in charge of finances, stores, and the secular business of the station. In December 1835 he requested the appointment of an overseer to conduct the station business, against the advice of Handt who argued that the expense could not be justified, and offered to take on some (or indeed all) of that work. Nothing more was heard of the idea, until Handt, seizing the occasion of his wife’s ill health, went to Sydney and refused to return to his posting. He was replaced at Wellington Valley by J. Günther, the second ever Basel candidate to come to Australia. It was at this time that Watson expressed resentment of the ‘preference’ shown by the CMS for German recruits.

At Moreton Bay (1837-1842)

Handt was sent to the Moreton Bay penal colony in 1837 as chaplain for the convicts and CMS missionary to Aborigines. The penal colony had not had a chaplain since Reverend John Vincent came and left in 1829.He immediately set upon learning the local language and when the Gossner missionaries arrived to set up Zion Hill mission, he was able to assist them with some knowledge of Turrbal, the local language. Handt also acclimatized pineapples from India, which he propagated near the present Treasury building in Brisbane city, and which he later gave to the Zion Hill missionaries. He now had a government salary of £100 per annum, acting as protector of Aborigines in which capacity he reported to Sydney. [10]

In 1840 Watson was dismissed from Wellington Valley and the CMS requested that Handt return there, but he refused. The Pietist attitude instilled in Basel graduates reinforced their expectation that they must follow their calling, which took the form of a calling to a particular posting (Berufung). But Handt clearly had a more secular attitude to his postings, having left Sierra Leone, and Wellington Valley, and now refusing to return there.

This independence of spirit did not endear him to the CMS. Two years later he was left stranded when the Moreton Bay convict settlement was disbanded, his services as convict chaplain were no longer required and his salary was withdrawn. Handt had fulfilled all the functions of a clergyman, but the Anglican bishop simply refused to re-ordain him as an Anglican priest and instead appointed an English priest to Moreton Bay. Both the government and the CMS washed their hands of him. At the same time both Zion Hill and Wellington Valley were closed down, abruptly halting the German missionary effort in New South Wales. Handt remarked ‘we were blamed for failure though others failed before us’.[11]

At Sydney (1842-1854)

Handt now was without income and without support, humiliated and desperate. He turned to Rev. J.D. Lang and moved to Balmain because ‘Lang said I could preach in his chapel, he also promised much besides’. Lang held out the prospect of a salary of £100 per annum, but nothing came of it. Instead Handt received a payout from the mission society of £114, with which he built a cottage at Lindfield, and opened a boys’ school.[12] He was not able to obtain a parish position, which Günther (his successor at Wellington Valley) supposed was because of his Reformed Church background (based on the teachings of Zwingli and Calvin, rather than on Luther).[13]

His disillusionment with both the Anglican Church and with Lang was shared by Christopher Eipper, who knew him from Zion Hill. The Anglican bishop having cut him loose, Handt had no choice but to throw himself onto the mercy of Lang ‘who led him, like us and many others, astray with promises lacking in nothing except their keeping.’ In 1846 Günther observed that of the three Basel graduates then in Australia, Handt was acting as teacher, Eipper was preaching at Braidwood, and he himself was at Mudgee, but ‘all long to be able to do something for the heathens.’ [14]

Mary Handt’s fourth confinement in 1844 did claim her life, and Johann, now 51, raised their three children, Wilhelm, Sarah and Ambrosius, by himself. Sarah died in 1848.

In 1854 Handt returned to ministering to prisoners as he had done on the Eleanor, in Sydney, at Wellington Valley, and at Moreton Bay. He became pastor at the prison hospital in Geelong where he died at age 70 in July 1863. His communications with the Basel Mission Society consisted of only four letters, one from Wellington Valley in 1835, two from Moreton Bay in 1838 and 1841, and one in 1850 from Balmain. All expressed the disappointment, humiliation, pain and adversity that characterized Handt’s missionary efforts. .[15]

[1] Handt letter to Coates, Missionary House, London, July 1832. The following details are all taken from the correspondence transcribed on WellPro Directory, The Wellington Valley Project, by Hilary Carey and David Andrew Roberts.

[9] Handt letter to Basel, 3 February 1836, Basel Archives, Brüderverzeichnis und Personalfaszikel, Akte 58.

[15]Theile, Otto, One hundred Years of the Lutheran Church in Queensland, Lutheran Church of Australia, Milton, 1938, p. 4; and Basel Archives, Brüderverzeichnis und Personalfaszikel, Akte 58.