Hermannsburg Mission Society (Hermannsburger Missionsgesellschaft - HMG) was founded by Ludwig Harms in 1849 in a spirit of post-revolutionary revivalism and rebellion. Hermannsburgers were active in Australia for thirty years and tended to adhere to a strictly Lutheran confessionalism, which contributed to the factionalism dividing the Australian Lutheran communities for decades. It has become a centre for world mission and operates today as a mission society of the Lutheran state church of Hannover (Lower Saxony).

Hermannsburg missionaries became involved in Tswana and Zulu missions in South Africa, Tamil and Dalit missions in India, Tartar missions in Georgia, Kurdish missions in Persia, missions in Brasil, Ethiopia and central Africa and the ‘inner mission’ among immigrants in North America and elsewhere.

In New Zealand they were involved in Maori mission (1876-1892) and in Australia in the well-known missions to the Dieri (1866 to 1874, at Coopers Creek) and among the Aranda (1875 to 1894 at Finke River, Hermannsburg). Hermannsburg graduates in the Brisbane area formed the German-Scandinavian Lutheran Synod which initiated a mission at Mari Yamba.

Ludwig Harms and the Restoration

Ludwig (or Louis) Harms single-handedly founded the seminary in 1849 with the symbolic number of twelve candidates, just like

Gossner had started in 1836. Harms was a founding member of the Norddeutsche Mission in 1836 based in Hamburg, which consisted of Lutheran and Reformed Protestants (the latter following the teachings of Zwingli and Calvin). Within a few years the Reformed Protestants split off and moved their mission headquarters to Bremen. Harms essentially sought to continue the Lutheran mission institute, but his purchase of a building in 1849 presented the Lutheran state church with a fait accompli and they considered it merely a ‘private initiative’. This non-recognition later became an argument used by successive directors in defence against church unionism as the Hermannsburg Mission Society (HMG) fiercely defended its confessional and organisational independence.

Harms wanted the HMG seminary to offer opportunities for uneducated boys to engage in evangelical work. Eight of the first twelve candidates were peasant boys from the surrounding area, the Lüneburger Heide (Heathlands of Lueneburg). One of the earliest photos is a collage with the heads of the candidates superimposed on figures in dark suits and polished shoes. Many of the group photos also demonstrate brotherliness among the candidates through linking of arms or hands.

The idea that uneducated peasants could be turned into priests undermined the more prestigious theological colleges that formed the core of the most established universities, which maintained class distinctions through market mechanisms, because a university education was well out of reach of the less well off. When it came to ordaining the first cohort of candidates, the Hanoverian church authority (Konsistorium) found an insurmountable ‘defectus scientiae’ in the candidates who had been neither trained in the old languages nor in science and theology

.[1]

Harms had a reputation for being strong-willed. He had been suspected of Pietism and suspended from his priesthood in 1841 for changing the text in which he delivered the obituary of Queen Friederike of Hanover. Pietism, or the holding of ‘conventicles’ had been outlawed for a century in the kingdom of Hanover with a log of regulations aimed against the Moravian Unity of Brethren. The Brethren were actively recruiting mission candidates in the area. Harms also sapped some support from the Norddeutsche Missionsgesellschaft with his new institution. He recruited some of its candidates, took over some of its chattels, and managed to re-direct some of the support of local mission support groups to his institution.

The revivalist movement had brought forth a quick succession of mission support societies around the Hanoverian kingdom and beyond (e.g. Hamburg 1822, Stade, Lehe, Celle, Grossmunzel 1829, Lüneburg, Hildesheim 1833, Hannover, East Fresia, Hameln 1834, Strasbourg 1836). These were not primarily aimed at ‘heathen mission’, but at ‘inner mission’, domestic evangelical activities. Such support societies raised funds for spiritual mission and institutions such as orphanages or seminaries.

From the beginning Harms subscribed to a narrow Lutheran confessionalism:

We Lutherans have the purest and most unadulterated confession. This is why I do not want you to have a confessional union with Catholics and Reformed Protestants. You are not to enter into a union with the others, but we shall remain unshakably true to our confession

.[2]

Harms abhorred ‘monkey and democratic business’, such as the democratisation of parish councils. The German kingdoms had been shaken by the March Revolution of 1848, a nationalist democratic republican movement demanding freedom of assembly, the abdication of kings, and a national parliamentary government. Harms was representative of the authoritarian and anti-democratic Restoration of the second half of the 19th century. He and his brother Theodor, who succeeded him in 1865, were deeply loyal to the Hanoverian royal family. The HMG directors continued to maintain close connections with the exiled Hanoverian royal family in Switzerland even in the 1920s, sixty years after its demise

.[3]

Although he himself was of a rebellious nature, Louis Harms expected above all obeisance from his candidates whom he considered his ‘children’, and who had to address him as ‘father’. His authoritative nature and the disciplined daily rhythm at the college stifled independent and critical thought. The daily life was strictly regimented from prayer service at 6.00 to the last lesson for the day ending at 22.00. Next to 28 hours of lessons per week, the candidates had to perform much physical labour, under conditions of strict regimentation and absolute celibacy. One candidate died in 1851, another in 1853, and two left in 1853. Those who left the seminary or wished to get engaged were publicly chastised. The Brothers were expected to be as dextrous with axe and dung fork as with book and pen, according to Harms.

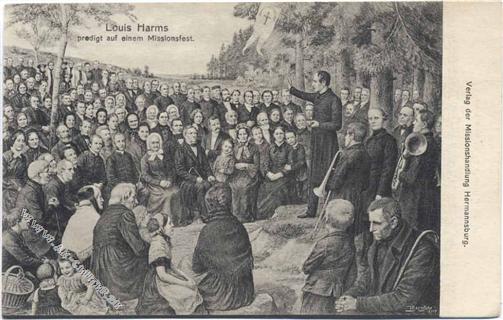

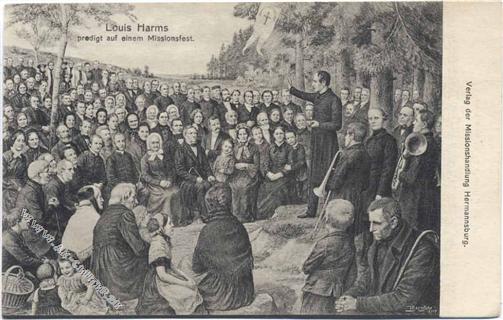

| Louis Harms preaching at Hermannsburg |

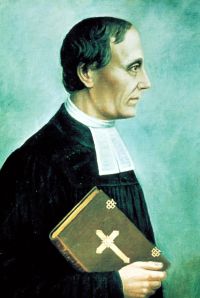

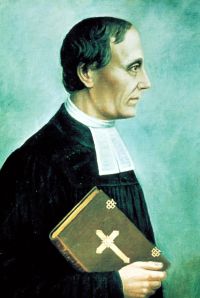

Louis (or Ludwig) Harms |

Louis Harms |

|

|

.jpg) |

|

Harms is credited with great personal magnetism.

Source: Hermannsburg Mission Society

|

Source: Hermannsburg Mission Society |

Pipe-smoking was one of the personal vicissitudes

that marked Harms as a man of the people.

Source: Hermannsburg Mission Society

|

Ludwig Harms practically denied his excellent education and turned into a charismatic peasant leader

[4]. He used deft language in the lower German dialect (Plattdütsch), combined with ‘a tendency towards superlatives and the conflation of the word of God with the word of the sermon’

.[5] He was an avid pipe smoker and story teller and had a gift for embedding historical events with mythology. Satan was easily invoked in his speech and against majority opinion and church law of 1864, he insisted that baptism expressly included an avowal of the devil. When he took on the Hermannsburg parish in 1849 he performed a public ceremony which involved a mutual oath between himself and the parishioners like a marriage oath (‘rise up and speak after me’) vowing Christian love, loyalty, support in aversity, and ‘never to divorce from me until God doeth us part’

.[6]

A great deal of loyalty and personal adoration was expressed for Ludwig Harms. One of the college lecturers, Carl Phillip von der Luehe, who had followed Harms to Hermannsburg, used to hold the Bible (in Plattdütsch) for Harms to read out during bible readings in the manse. External observers sometimes commented on the exaggerated peasant pride that suffused Hermannsburg and the personal cult that had arisen around Harms.

Harms saw heathen mission in close symbiosis with religious Revivalism at home: ‘The best thing is, that the blessing that we help to bring to the heathens will fall back on ourselves thirty times over in the blossoming of faith and love and hope in our congregation.’

[7] By the 1850s Hermannsburg township had become a tight-knit Lutheran congregation supporting heathen mission with liberal donations, spurned by annual mission festivals. One of the locals is reported to have said (in Platt), as he dropped his donation for the missions into the collection basket: ‘Dat is foer de Heiden, dat se ok bald so glücklich werd, als wi suend’ (‘that’s for the heathens, so they’ll soon be as happy as we are’).

[8]

In 1853 the first cohort of candidates were ready for sending out after four years of training. The congregation commissioned the building of its own boat, the Candace (named after the African Queen in Apostles 8, 27; decommissioned in 1874) to send to the Galla (Oromo) people in Ethiopia, apparently at the instigation of sailors’ reports from that region. This effort was foiled by the resistance of the Sultan of Muskat (Oman), and a Zulu mission (called Hermannsburg) was started in South Africa instead. This represented the first missionary activity, followed up with a second cohort of graduates sent out in 1857, and a third in 1862.

By this time crises in discipline were festering in the seminary. Three candidates who wished to get engaged were expelled in 1857. The candidates were supposed to stand by the personal oath of loyalty given to Ludwig and Theodor Harms, and those who preferred to get engaged were referred to as oath-breaking scoundrels (‘ bundbrüchige Schurken’). Soon afterwards a group of ten demanded a change in teaching style, and were summarily expelled. They went to America following their brother Bading who had been expelled in 1853 and became a leading figure in the Wisconsin synod.

In 1864 the mission activities were extended to India, again at the instigation of a single report, which turned out to be unreliable. The request for assistance had come from a former Norddeutsche Missionsgesellschaft missionary Wilhelm Groenning, who had been working in the Madras province (now Andhra Pradesh) for American Lutherans and who had become isolated as a result of the civil war in the United States. When August Mylius arrived in Madras from the HMG in 1864 he found that the American Lutherans had neither requested assistance nor did they welcome HMG involvement. Mylius also had confessional differences with Groenning over the taking of communion, mostly because the HMG insisted on communal supper regardless of caste, whereas the Indian social elites resisted this. Mylius started another mission in an area bordered by the activities of American Presbyterians, American Baptists, British Methodists, the Scottish Free Church, and the London Mission Society. This mission field prospered easily because of the willingness of Dalits (untouchables) to turn away from the Hindu caste system.

Under Ludwig Harms the missionaries were not paid and all chattels belonged to the mission society. It meant that all expenses had to be reported and recouped from the HMG. This led to extreme economy because each item of expenditure had to be defended and explained. Much correspondence was spent on whether it was preferable to travel on foot to be ‘close to the people’ or purchase a horse or even a wagon to get around faster and with less exhaustion, or whether to build a cheap hut or a more substantial and permanent dwelling. Books that could have familiarised the new arrivals with the area in which they were to missionise were considered a luxury. It took twenty years of mission activity to replace this system, amounting to beggar monks, with wages for the missionaries.

Theodor Harms and the Kulturkampf

Religion and politics were always closely intertwined in the HMG and this gave rise to a certain inflexibility that inevitably affected the overseas missions. Theodor Harms waged a multilateral war against caste, polygamy, slavery and confessional unionism and therefore clashed with practically all established authority at home and in the mission fields in India and Africa.

The Prussian annexation of Hannover in 1866 represented a double assault on the convictions of the HMG leadership – on their king and on their faith. The HMG had become a bastion of confessional Lutheranism and resisted the Prussian Unionism of Lutherans and Reformed Protestants. The directors were also fervent Hanoverian royalists, and a former Hanoverian army major was on the mission society committee. Chancellor Bismarck’s statae-building program involved wresting powers from the churches, particularly the dominant Catholic Church. In the process of this battle over culture (Kulturkampf 1871-78), Bismark instituted a state school system and civil marriage. Theodor Harms refused to recognize the new church protocols on marriage and was therefore suspended from the Hermannsburg parish by the Lutheran state church. He formed the Hanoverian Lutheran Free Church in 1878. This split was also carried into the Australian synods (see below). The stated purpose of the HMG mission society became ‘to build up the free Lutheran church in the heathen world’ but the mission committee consisted of members of the free church and of the state church for several years. It was no longer possible to require all member congregations to channel their donations to the mission society, but donations continued to flow in from as far away as the Alsatian parishes in Strasbourg and Bischheim. In late 1890 another split occured in the Hermannsburg Lutheran community. Another free church formed with specific responsibilities for the New Zealand mission, so that the small township of Hermannnsburg now had two Lutheran free churches and the Lutheran state church. Members from all three churches were represented in the mission committee and in the South African mission, eventually impacting on that mission.

Egmont Harms and the German empire

Theodor Harms died in 1885 and a number of opinions were expressed against appointing his son Egmont as successor (who had passed his theological exam in Bavaria on condition that he would never seek an appointment in that state) but due to the lay influence on the committee and the peasant tradition of family succession he did become director, with Johann Gottfried Oepke as co-director.

Emperor Wilhelm II promoted colonial missions and the HMG readily participated in the expanding empire, offering to take over the Moravian Brethren’s mission in German East Africa. The peasant model of the founder Ludwig Harms was no longer adequate. The curriculum was profoundly revised, with the inclusion of bible languages. In the first year of the seminary in 1849, only German and English had been taught. Latin was introduced into the curriculum in 1861 due to pressure from the State church. By 1892 it included German, Latin and Greek in the first year, and English, Latin, Greek and Hebrew in the 3rd year. The ‘aspirational’ year that had been inserted before the three-year course, and which consisted of physical labour and some study, was replaced with the requirement to attend the HMG Christian school for a year during which aspirants paid school fees and supported themselves.

At the outbreak of World War I the students from Russia and South Africa at the HMG were interned at Ruhleben near Berlin. The other candidates were required to perform military service and a number of them became prisoners of war. HMG missionaries in India were interned and repatriated and the assets of the South African mission were appropriated, and the missionaries interned. Germany lost its colonies in the war, and the newly commenced German East Africa mission was terminated. The HMG directorate decided to place more emphasis on home mission to combat the widespread secularism among Germans.

Christoph Schomerus and the Third Reich

In 1922 the HMG joined the German Protestant Mission Association but continued to defend itself against integration into the Prussian state church. But a greater threat to independence presented itself in Hitler’s Kirchenkampf (struggle with the churches) with pressure to integrate into the protestant state church (Reichskirche). Schomerus became embroiled in the debate raging in the Lutheran state church over integration into the Reichskirche.

HMG students and staff enthusiastically supported national socialism by participating in public events, particularly the Society's co-director based in South Africa, Winfried Wickert. The South African mission was strongly coloured by national socialist tendencies, even sending donations to Germany for use by the state people’s welfare (Volkswohlfahrt).

[9] But Director Christoph Schomerus noticed with concern that the state church, whose 1933 annual assembly ended with ‘Sieg Heil’ instead of with a prayer, was being secularised, and resigned from the state church senate in protest.

Schomerus thought it prudent not to be too closely aligned with this regime. He referred to the close connections with Lutheran churches abroad, and the fact that an Alsatian priest who supported the mission and had commemorated the Führer’s birthday in the church newsletter had been suspended from office. The national socialist government made mission business difficult with restrictions on the transfer of funds abroad and it forbade the collection of donations outside of the state churches. From 1940 even church newsletters came under censorship and the mission newsletter had to be suspended. In 1939 the secret state police (GeStaPo) refused permission for the annual mission festival because it coincided with an NSDAP party assembly, and permission had not been applied for ‘properly’. Schomerus deferred the festival to later in the year, but was refused the use of the farm premises he requested. On the day of the festival a number of seminary students received their call up into the army.

While director Schomerus in Hermannsburg was concerned about the increasing infringement of mission work by the national socialists, co-director Wickert in South Africa flew swastikas at the mission stations and had the Horst Wessel song, the Nazi party anthem (‘The flag on high’) performed. He also supported the selling of shares in the new South African Mercedes subsidiary, a scheme by which missionaries were able to circumvent the restrictions on foreign currency exchange and were tied into the economic goals of the Reich. The pressures at home splintered the Lutherans in South Africa. The south-west synod joined the Reich church, whereas the Johannesburg congregation held fast to the Lutheran free church.

The ardent national socialism of part of the HMG leadership and membership made it impossible to assist German Lutherans of Jewish descent who were being suspended from office and sought an overseas posting. The HMG mission society declined a number of such requests with reference to the strong national socialist thought in South Africa itself.

The economic upturn during the Hitler regime led to a decline in applications to enter the seminary. Only two new candidates joined in 1935, and by 1940 there were seven teaching staff and only 20 students. The mission school was closed altogether from Easter 1940 to autumn 1945, when only nine students returned. Many had died in military action. In 1943 August Elfers replaced Schomerus as director. He invited a bishop to deliver a public address who was known as a supporter of the Nazi regime.

Hermannsburg remained a close-knit religious community. It had always been in some competitive tension as well as cooperation with other Lutheran and Protestant mission societies with whom it shared mission fields and financial support from congregations. The Leipzig Mission Society (founded in Dresden in 1838), which was engulfed in secularist socialist Germany from the end of World War II to the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, was practically incorporated into the Hermannsburg Mission Society after the reunification of Germany.

The HMG and Australia

The HMG interest in Australia and New Zealand was always minor. None of its directors ever visited, and missionaries rarely returned to Germany on furlough. Formal arrangements, such as ownership of property and decision-making powers seemed to be of much greater issue for the HMG directors than the health, welfare and commitment of staff. Prominent in the mission historiography of the HMG and the South Australian Lutherans are issues of confessional detail which appear minor to the non-Lutheran observer, such as who could be admitted to holy communion, to what degree to collaborate with the unionised state church, questions of millennialism and predestination which seemed to always prescribe which parts of the varied body of Lutheran organisations could be cooperated with. In these histories factionalism and dispute overshadow the unifying love of God and faith in Christ, which was meant to underpin all their efforts.

The initial immigration of Germans to South Australia commenced with a Lutheran congregation around Pastor A.L.C. Kavel arriving in 1838, followed three years later by a congregation around pastor G. D. Fritzsche. South Australia remained the focus of German migration although substantial numbers were also recruited to Queensland and Victoria. The failed German Revolution of 1848 and the discovery of gold in Victoria gave new impetus in the 1850s.

The German Lutheran communities from Silesia and Posen that settled near Adelaide in 1838 and 1841 had escaped the Prussian state pressure to join the union church. They soon split into two synods under two pastors because of confessional differences, for example concerning Revelations 20, out of which some constructed a millenarian expectation of a thousand-year Reich.

Their migration had been facilitated by George Fife Angas, a commercial underwriter of the South Australian settlement scheme, who also searched for missionaries to settle in South Australia. He recruited four from the new mission society in Dresden (founded in 1836). Two of these, Schuermann and Teichelmann, arrived a few weeks before the German settlers in 1838. They operated without support from Dresden and in isolation, with only occasional financial support from the Governor. Other German missionaries at the time were Rev.

Handt from

Basel who had arrived in 1831 for Wellington Valley, and the Gossner group who commenced

Zion Hill mission, also in 1838.

The growing German Lutheran communities in Australia required pastors, and the missionaries sent to various missions provided an unexpected source. The four Dresden missionaries who arrived in South Australia in 1838 and 1840 (Teichelmann, Schuermann, Meyer, and Klose) soon entered into service in Lutheran communities, much like the two missionaries (

Schmidt and

Eipper) and a number of the lay helpers sent from Berlin to Brisbane.

The mission institutes in

Basel,

Neuendettelsau, Berlin and Hermannsburg continued to receive requests for pastors. Altogether 32 HMG pastors were sent to Australia, seven of these entered migrant community service after a period on missions, the other 25 were destined as pastors. Another eight candidates were sent from the German migrant communities to study at the HMG.

None of the HMG pastors joined the Immanuel Synod that had initiated the contact with the HMG over the Dieri mission (see below). The Immanuel Synod was accused of tending towards chiliasm, which was anathema to the Hermannsburg dogma

.[10] Most of the HMG candidates entered into the South Australian synod instead, so that the HMG influence in this synod became very dominant. This was the synod that grew out of the second group of German arrivals in South Australia centred on Pastor Fritzsche at Lobethal near Adelaide and Pastor Myer at Bethanien in the Barossa Valley. This synod first called itself the Bethanien-Lobethal Synodalverband, then the South Australian Synod, later the Evangelical-Lutheran Synod of Australia (ELSA) and finally the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Australia.

This synod formed a mission society with the Immanuel Synod to commence a mission in Australia at Coopers Creek. They entered into collaboration with the HMG over this mission venture in 1861and divided their donations between the missions conducted by the men from the Leipzig Mission Society and the HMG. Later they retained their collections for use in South Australia (Hermannsburg) and Queensland (Mari Yamba).

Fritzsche and Meyer died in 1863 and 1862 respectively, so that successors were required, and Hermannsburg (Germany) sent Georg Adam Heidenreich and Carl Gottfried Hellmuth in 1866. Both formed splinter synods in Australia. Hellmuth moved to Queensland and became instrumental in forming a Hermannsburg-leaning synod there, splitting the Lutherans in Queensland. This synod founded

Mari Yamba mission in 1887 rather than joining forces with the Immanuel Synod to support

Cape Bedford (later Hope Vale). Heidenreich became a champion of Hermannsburg interests in the dispute over the continuation of the Arrernte mission at Finke River (see below). As a result of this dispute, Heidenreich and his son, who had just graduated from Hermannsburg, were excluded from the South Australian Synod (now ELSA) in 1902. Heidenreich then formed the splinter synod ELSA a.a.G., meaning ‘Evangelisch-Lutherische Synode von Australien auf alter Grundlage’ (‘along original lines’). This became the Australian district of the Ohio synod in 1910 which grew to six parishes with seven pastors, including three from Hermannsburg (Heidenreich Jr, Ph. Scherer and W. Roehrs coming via Ohio). In 1926 the ELSAaaG splinter synod finally joined the Lutheran Church of Australia formed in 1921.

More pastors arrived in South Australia from the HMG: three in 1875, six in 1877, four in 1882, and another four in 1888/89. Others came into German communities from mission service: Johann Friedrich Goessling (later involved in the

Mari Yamba committee), Ernst Homann, Carl Schoknecht, Adolf Hermann Kempe, Wilhelm Friedrich Schwarz, Louis Gustav Schulze. Among the better known HMG candidates in Australia were Friedrich Wilhelm Albrecht (at Hermannsburg mission 1926 to 1951), Hermann Heinrich Vogelsang (at Killalpaninna from 1866), and the lay missionary Georg Christoph Freiboth (at Hermannsburg mission 1882 to 1894).

Both the beginning and the end of the working relationship between the HMG and the South Australian Lutherans were overshadowed by controversy. Even before the South Australian synods entered into collaboration with the HMG over a heathen mission in 1861, Harms at Hermannsburg had recommended the posting of Dr K. H. Loessel to Hamilton in Victoria. Harms soon regretted this recommendation of a person whom he did not personally know. A candidate who had been dismissed from the HMG just prior to his final exams, P. G. Jacobsen, decided to accompany Loessel. Loessel took it upon himself to ordain Jacobsen and engage him as a teacher at Germantown (Grovedale) in Victoria. This caused a rift in the community and earned much publicity. Still, Jacobsen and his communities were accepted into the South Australian synod in 1864, since he held such a ‘distinctly Lutheran’ position. Harms meanwhile distanced himself from Loessel, who was evidently ‘unable to subject himself to the church regulations’

.[11]

The HMG split with the South Australian Synod

The anti-chiliastic attitude at the HMG strengthened its affinity with the South Australian synod, which sought to distance itself from its sister Immanuel Synod. But other confessional and operational differences developed to create a rift with the mother institution.

The South Australian synod welcomed Harms’ departure from the state church and creation of a free church in 1878, because the South Australian Lutherans themselves had left Germany in protest against union with the state church. But the reason for this split, over the new Bismarckian rules on civil marriage, was not thought to be a valid reason. The South Australians wanted the HMG to completely sever its links with the state church rather than retain members of the state church on the institute’s board.

The South Australian synod was strengthening its links with the Missouri Synod, whose trainees were much better able to operate in an English-speaking environment than those from the HMG. In 1879 it first requested pastors from there, and increasingly young candidates were sent from South Australia to train in Missouri instead of at the HMG. Eventually the South Australian Concordia College for theological training was opened, and its second director drawn from the Missouri synod.

Meanwhile Harms entered into a theological struggle with the American Missouri Synod. The Missouri Synod took the position on predestination that some men were destined by God to be saved and others to be damned. In 1881 Harms publicly attacked this position as too close to the reformed state church. This drew the South Australian synod into a division over allegiance to either the HMG or Missouri.

Another issue was that Harms (unlike the Missosuri Synod) retained the right to assign those who had been sent as missionaries, even once they entered into service into a German community. He only exercised this right to reassign in two cases, but it led to uncertainty among the ex-mission pastors about how long they could stay in their communities.

The final blow came when in 1890 the HMG made a controversial rapprochement with the state church to facilitate collaboration on overseas missions by agreeing to mutually admit their members to the holy communion (Abendmahl). Many pastors in the free church in Germany objected to this, and for Missouri and the South Australian synod this represented the ultimate surrender to church unionism, the very issue that had inspired their emigration from Germany. In 1892 most of the pastors in the South Australian synod (ELSA) who had originated from the HMG were in favour of dissolving its relationship with the HMG in Germany

.[12]

The last two pastors to arrive from the HMG at the instigation of mission superintendent Heidenreich faced a difficult reception. Their ordination by the synod president Rev. Phillip Oster was met with protest. Rev. Franz Hossfeld was required to sign a declaration that he realised that the position taken in the HMG was against the Lutheran confession. The other, Rev. Warber wanted to retain a working relationship with the HMG and was only allowed to enter into mission service. Rev. Ernst Homann, a former HMG candidate, was among the most vocal resistance to the ordination of these two

.[13]

In 1895 the synod again discussed the necessity of separating itself from the HMG, with a long presentation by Pastor Dorsch from Missouri demonstrating that the HMG had entered a union with the state church. Only four of those present tried to defend the HMG. Hoefner and Hossfeld were immediately excluded from the synod, whereas Heidenreich, and his son who had just completed his training at the HMG, were excluded a few years later, in 1902. Thus the very synod which had received most of its pastors from there, dissolved its relationship with the HMG.

HMG alumni made up a quarter of all Lutheran pastors in Australia for the first few decades. Harms observes that their predominant peasant background helped them to oversee the predominantly rural German migrant population

.[14] During and after World War I it became increasingly necessary to speak English rather than German, and many of them were either unable or unwilling to do so. HMG alumni rarely took leading positions in the church, they occasionally took on teaching functions in the local schools or acted as travelling priests, but generally they serviced small local communities

.[15] All but five of them finally distanced themselves from the HMG over the question of church unionism.

The Australian missions with HMG staff

In Australia HMG alumni were involved in the Coopers Creek Mission (from 1866 to 1874) Hermannsburg Mission (from 1875 to 1894) and Mari Yamba (from 1887 to 1893). All three missions were troubled by confessional splintering.

The HMG was already active in Africa (since 1853) and had only just commenced its mission field in India (1864) when a request came from South Australia for assistance with a mission at Coopers Creek. A new mission house had just been completed and Harms now expected to be able to send out 24 missionaries every second year, so that new mission fields were welcome. The idea that local Christian communities overseas were able to support such an undertaking seemed particularly promising.

Ludwig Harms embraced the idea of collaborating but was ill informed about the conditions. He thought that only a few Aborigines were left in New Holland, and that the Lutheran settlements were about 120 miles away from the proposed mission.

Shortly before his death in 1865 he declared in a letter to South Africa.

You will also be pleased that I must inform you that God has opened up a new field of influence for our mission. In New Holland numerous populations of natives have been discovered near the interior salt lakes, who are proving themselves to be capable of education and welcoming. Not too far away, perhaps 120 English miles, twelve Lutheran communities have settled who are urgently asking me for missionaries for the heathens, and who have undertaken to support them ….’

[16]

Harms insisted that the HMG would have the decisive control over the mission, and that the two south Australian supporting synods had to form a local committee responsible for the financial affairs of the mission. Any surplus funds raised by the committee were to be channeled to the HMG to support the training of further missionaries, since a heathen mission was not to accumulate capital. Harms wanted to send both trained missionaries and lay assistants, whom he referred to as mission colonists, to facilitate the founding of at least partly self-supporting missions. It made beautiful sense on paper.

In 1866 the HMG sent two pastors and a lay helper for the new mission (arriving together with Heidenreich and Hellmuth, see above). After only six weeks in South Australia the mission party was sent on its way from Tanunda. The mission orders under which they marched were - contrary to Harms' vision - that they were funded by and therefore in the service of the Lutheran Church of South Australia. They were to take the advice of the South Australian mission committee and to report monthly. They arrived at their destination a few days after a competing party of German Moravian mission founders, and gradually realised that the land was getting rapidly taken up, Aboriginal owners resented the intrusions, and the water supply was steadily shrinking. One by one they abandoned the venture and were replaced by the HMG pastor Schoknecht, who was recalled in 1873. This represented the end of the HMG involvement in the Dieri mission at Coopers Creek (1868-73). The cooperation between the South Australian mission committee and the HMG was not considered successful, since the mission committee made decisions such as the shifting the mission station without reference to the HMG, and Theodor Harms on his part recalled Schoknecht without consulting the committee.

The cooperation between the two South Australian synods supporting the venture also collapsed when one of them sought unification with a Victorian Lutheran synod. In 1874 they parted company to undertake separate mission ventures. The Immanuel Synod obtained help from the Neuendettelsau Mission Society and shifted the Coopers Creek mission to

Lake Killalpaninna.

Meanwhile the South Australian synod received the larger part of the Coopers Creek mission property, particularly the livestock, and started Hermannsburg near the Alice Springs telegraph station in 1875, again with assistance from the HMG. The naming of this joint mission in the red centre reflects that HMG was claiming complete control of the Hermannsburg mission. Georg Heidenreich, the HMG pastor of Bethanien, was installed as Superintendent in South Australia, supported by an advisory council. The mission property was to be held in common between the South Australian Synod and the HMG, but in case the mission had to be abandoned all property would fall to the HMG.

This agreement was to lead to immense tensions when the South Australian synod withdrew from the venture in 1894. The Immanuel Synod acquired Hermannsburg mission and the HMG staff were replaced by the Neuendettelsau graduate Carl

Strehlow. In the sales negotiations ELSA (the former South Australian Synod) wanted to claim half of the assetts, while the HMG wanted to claim two thirds. Heidenreich was so committed to the HMG that he was excluded from ELSA in 1902. Carl Strehlow was succeeded in 1922 by another HMG alumni, Friedrich Wilhelm

Albrecht who stayed for 35 years, but this time the HMG made no claims on directing the mission.

[1] Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000.

[3] Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 45.

[5] Tamcke in Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 41.

[6] Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 42.

[7] Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 47.

[8] Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 47.

[9] Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 86.

[10] Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 463.

[11] L. Harms letter to Muenchmeyer, 16. 11. 1864, Hermannsburg 881 Ar.LA-LCA, cited in Hartwig F Harms ‘Die Arbeit in Australien und Neuseeland’ in Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 480.

[12] Hartwig F Harms ‘Die Arbeit in Australien und Neuseeland’ in Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 466-67.

[13] Hartwig F Harms ‘Die Arbeit in Australien und Neuseeland’ in Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p.467.

[14] Hartwig F Harms ‘Die Arbeit in Australien und Neuseeland’ in Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p.471.

[15]Hartwig F Harms ‘Die Arbeit in Australien und Neuseeland’ in Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 471.

[16] Ludwig Harms, 27. 7. 1865 to Hohls, cited in Hartwig F Harms ‘Die Arbeit in Australien und Neuseeland’ in Lüdemann, Ernst-August (ed) Vision: Gemeinde weltweit - 150 Jahre Hermannsburger Mission und Ev. Luth. Missionswerk in Niedersachsen, Verlag der Missionshandlung, Hermannsburg, 2000, p. 445.

.jpg)

.jpg)