The history of race relations between early settlers and indigenous people in the Logan district has been recorded by Europeans in government records, newspapers, manuscripts and journals, amounting to a fairly ethnocentric record of the contact between the pastoralists, the native police and the Yugambeh. In some instances the records contradict each other, a reminder that they present perspectives and recollections, rather than objective records of events. However, Yugambeh people themselves have used the extant records to reconstruct an Indigenous perspective on the early settlement of the Logan district. The limited documents available suggest that the relations between the early settlers of the Logan district, the Native Police and the Yugambeh was at times volatile, while at others relatively peaceful and respectful. In particular one individual, Bilin Bilin, emerges as an indigenous diplomat at the interface of race relations in the Logan area.

Pre-settlement history

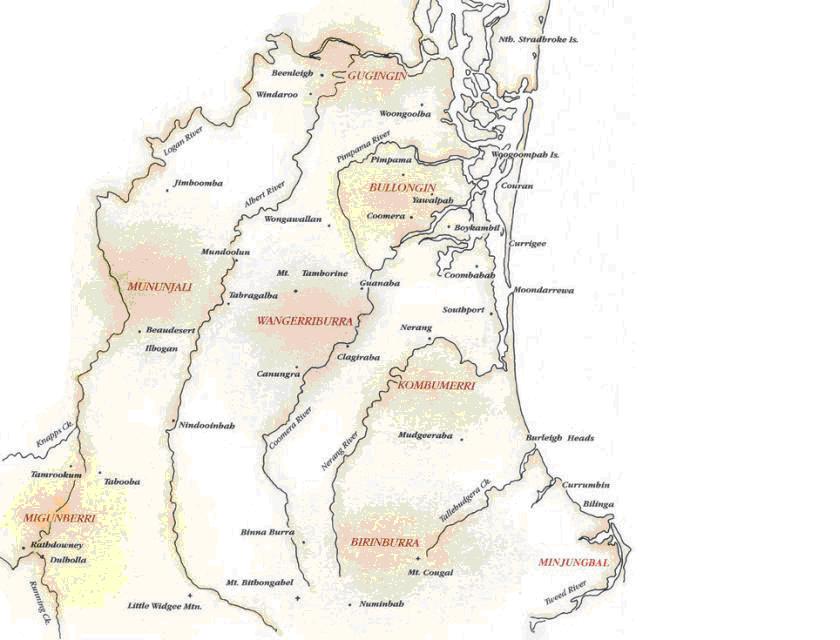

The Yugambeh people consist of eight traditional family groups identified as

Mununjali, Wanagerriburra, Migunburri, Gugingin, Birinburra, Bullongin, Minjungbal, and

Kombumerri (spelling may vary between different sources)

[1]. Archaeologists estimate that these families have been living in the Yugambeh region between the Logan and Tweed Rivers for over 24, 000 years. There are no official documents available that record how many Aborigines were living in the Yugambeh region at the time of early settlement of the Logan River. Similarly, there are few that describe the relations between the pastoralists, the native police and the Yugambeh Aborigines during the settlement period

.[2]

In August 1826 Captain Patrick Logan explored the Logan River, naming it the River Darling in honour of Governor Darling. In 1827 Governor Darling returned the compliment by renaming it the “Logan River”. To the local Yugambeh Aborigines it was known as Dugulumba.

| Map of the Yugambeh area |

|

| Source: Yugambeh Language and Heritage Research Centre |

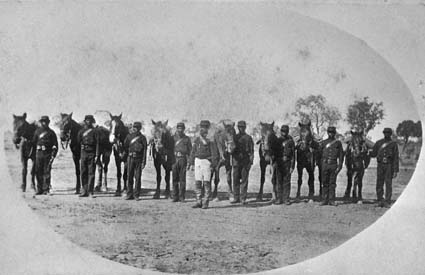

Native Police

With the arrival of early settlers to the Logan district in the early 1840s and the establishment of grazing leases, conflict arose as the Yugambeh Aborigines began to resist the loss of their land. In response to this resistance the Native Mounted Police were deployed to the district

.[3]

While there is little documented evidence of the conflict between the Native Police and the Yugambeh, recollections by Bullumm (John Allen) in the 1914 Queensland Parliamentary Papers provide a glimpse of the violence that occurred

.[4]

About his earliest impression of things was when a party of his tribe was surprised by troopers at Mt Witheren. The blacks – men, women, and children – were in a dell at the base of a cliff. Suddenly a body of troopers appeared on the cliff and without warning opened fire on the defenceless party below. Bullumm remembers the horror of the time, of being seized by a gin and carried to cover, of cowering under the cliff and hearing the shots ringing overhead, of the rush through the scrub to get away from the sound of the death-dealing guns. In this affair only two were killed, an old man and a gin. Those sheltered under the cliff could hear the talk of the black troopers, who really did not want to kill, but who tried to impress upon the white officer in charge the big number they had slaughtered. This police raid – one of many – had the usual excuse; the blacks had killed cattle and therefore had to be taught to let the cattle alone

.[5]

| Native Mounted Police in Queensland, 1863 |

|

| Source: National Archives Australia |

During evidence given by Lieutenant Frederick Wheeler, an officer of the Native Mounted Police, to the Select Committee on the Native Police Force in Brisbane in 1861, Lt Wheeler explains that such responses as these were due to an inability to determine who the guilty Aboriginal person was. Consequently, he held the entire tribe responsible.

By 1861 Lt Wheeler indicated that he had effectively 'dispersed' the Logan River Aboriginals from their land, driving them onto Stradbroke and Moreton Islands (where a short-lived Catholic mission from 1843 to 1846 had already been abandoned), or to Northern New South Wales

.[6] However, reports from newspaper articles and manuscripts dated after 1861

estimate that two to three hundred Aborigines from the Tamborine, Pimpama and Coomera clans had attended corroborees in the Logan area in 1864 and 1867, and that there were numerous sightings in 1869 of gatherings of at least 100 Aborigines from Nerang Creek.

Early settlement

With the separation of the colony from New South Wales in 1859 and the establishment of the Logan Agricultural Reserve in 1861, English, Irish and German immigrants rapidly began to settle in the Logan district. The inflow of Germans started in the 1860s, and the first mission was established at

Bethesda in 1866. Reminiscences from one of the first German immigrants in the Logan district depict a relatively conciliatory coexistence with the Yugambeh:

We had the Logan tribe frequently camped close at hand, near the present Lutheran Parsonage, Bethania, and we often went on full-moon nights to enjoy their corroberies … Although some of the more intelligent often and emphatically challenged the white man’s right to encroach on their lands and destroy their forests, and with them, their means of livelihood, we were never molested by them other than by begging

.[7]

Similarly, W.E. Hanlon recalled from the 1860s:

The food problem was a very acute one when first we settled on the Logan … There were many blacks in the district, but on no occasion did they give us any trouble. On the contrary, we were always glad to see them, for they brought us fish, kangaroo tails, crabs or honey to barter for our flour, sugar, tea or ‘tambuca’

. [8]

Hanlon’s family had to give up their Logan allotment, where most of the Germans persevered. There are many other stories which have been passed down through the descendents of early Logan settlers which also indicate a conciliatory relationship between the settlers and the Yugambeh Aborigines.

Bethesda mission

| Pastor Haussmann |

.bmp) |

| Source: Gunson 1960 |

Aiding the settlement of German immigrants in the Logan district at this time was Pastor Johann Gottfried

Hausmann, who also established two missions in the area with the dual purpose of a place of worship for both the German and English congregations, and as a place to “settle Aborigines, train them to work … and bring them into contact with the Gospel of Jesus”.

[9] Haussmann’s letters published in the

Australischer Christenbote record his belief that the natives of Australia were “meant to be saved”.

[10] They also portray a conciliatory relationship between himself and the Yugambeh Aborigines.

Up to date I have not been in a position to do something systematic for the poor natives. When they came to the Mission station we accepted them joyfully and proclaimed to them the Gospel and attempted to encourage them to work. A number of families from Nerang Creek, 30 miles from here, remained with us for several weeks, and I have now made a contract with them, namely to clear 10 acres of land, to burn the wood so that corn can be planted. All this is to be done for 1 pound an acre. They fulfilled the contract to my satisfaction, and as long as they were here they behaved quietly and peacefully. Also men, women and children worked here. The children seemed to reveal eagerness to learn and they seemed to understand quite easily. On Sundays they were also quiet, and on this particular day, we gave them clean clothing and they came with us to the Church, although the service was conducted in our mother tongue. Yet for two hours they sat quite still and with great devotion

.[11]

An indigenous diplomat

While active in the Bethesda Mission Pastor Haussmann taught Bilin Bilin, a “well-known and well-respected” indigenous man in the Logan district, to read and write. Bilin Bilin was also known as Jackey Jackey, Kawae Kawae, John Logan, Bilinba, or King of the Logan and Pimpama

.[12] Hausmann expressed the hope that ‘Jacky’ might become his ‘first fruit’, the first baptismal candidate in Queensland. Born in the early 1800s, Bilin Bilin (meaning 'many parrots”' became a leader of the Yugambeh people in about 1863, and in 1875 was given a 'king plate' which stated that he was 'King of the Logan and Pimpama'. In the brief documented history of Bilin Bilin’s life by his descendants, Bilin Bilin is described as a diplomat who 'demanded equality of wages for his people'

[13], is credited with aiding the survival of the early explorers and settlers to the Logan district.

Bilinba charged Lutheran Missionary Haussman … 5/- per week to sit and discuss religion with the tribe. The tribe cleared 10 acres of land at the rate of 1 pound per acre. Surveyor Roberts had to plead for additional funding because he had to pay our people to ‘hump’ his supplies over Tamborine Mtn. Other expenses included weapons to shoot other tribe members who were pilfering ‘humped’ supplies

.[14]

Throughout the settlement period Bilin Bilin encouraged the Yugambeh Aborigines to live on their land. With the introduction of the Aborigines Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act in 1897 most of the remaining Yugambeh were removed from their land to Aboriginal missions and reserves throughout Queensland. Bilin Bilin resisted the pressure from the Southern Protector of Aborigines, Archibald Meston, to live in an Aboriginal reserve until the late 1890s, when old age saw him relocate to the mission at Deebing Creek, where he passed away in 1901. At the time of his death Bilin Bilin was considered to be “the last of his tribe”.

[15] However, a reunion organised by Ysola Best and others in 1987 resulted in the gathering of 300 of his descendants.

[16]

|

Deebing Creek Mission 1890s,

with Bilin Bilin in the front row

|

Bilin Bilin ca 1890s |

Bilin Bilin ca. 1900 |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

| Source: Buchanan 1999 |

Source: O'Connor 1987 |

Source: Buchanan 1999 |

[1]O'Connor, R., The Kombumerri: Aboriginal people of the Gold Coast, National Library of Australia, 1997, p. 6.

[2]Best, Ysola and Barlow, A. Kombumerri – Saltwater People, Heinemann Australia 1997.

[3]O’Connor, R. The Kombumerri: Aboriginal people of the Gold Goast, National Library of Australia, 1997, p. 57. Best, Ysola and Barlow, A., Kombumerri – Saltwater People, Heinemann Australia 1997, p. 61.

[4]Miller, A, ‘Bilin Bilin, King of the Logan’, Albert & Logan News, Sunday 30 May 1993, p.14 . O’Connor, R., The Kombumerri: Aboriginal people of the Gold Goast, National Library of Australia, 1997, p. 57.

[5] Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aborigines 1913, Queensland Votes and Proceedings 1913, p. 24.

[6] O’Connor, R. The Kombumerri: Aboriginal people of the Gold Goast, National Library of Australia, 1997, p. 59.

[7]Holzheimer, ‘Reminiscences of the pioneering days on the Logan’, 26 January 1922., pp. 4-5. Mr. Holzheimer was nine years old when he arrived with the first German settlers at Bethania on the Black Diamond on the 23rd February 1864. He was among the group settled by Rev. Hausmann at Waterford.

[8]Hanlon, W.E. 1935, ‘The early settlement of the Logan and Albert districts’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 209-210 in Best, Ysola and Barlow, A. Kombumerri – Saltwater People, Heinemann Australia 1997, p.14.

[9]Theile, Otto, One hundred Years of the Lutheran Church in Queensland, LutheranChurch of Australia, Milton, 1938, p. 172. Lohe, M. ‘Pastor Haussmann and Mission Work from 1866’, Translation from Australischer Christenbote, Lutheran Archives Australia, 1964, p.18.

[10] Nolan, J. ‘Pastor J.G. Haussmann: A Queensland Pioneer 1838-1901’, University of Queensland, BA thesis, 1964, p.110; ‘Conference of the EvangelicLutheranChurch’, The Brisbane Courier, 11 June 1870, p. 6.

[11]Lohe, M. ‘Pastor Haussmann and Mission Work from 1866’, Translation from Australischer Christenbote, Lutheran Archives Australia, 1964, pp. 7-8.

[12] Buchanan, R., Logan: rich in history, young in spirit. A comprehensive history. Logan City Council, 1999, p. 12, p. 65. Steele, J. G. Aboriginal Pathways, Queensland University Press, St. Lucia, 1983, p.81.

[13] O’Connor, R. The Kombumerri: Aboriginal people of the Gold Goast, National Library of Australia, 1997, p. 65.

[14] Steele, J. G., Aboriginal Pathways, Queensland University Press, St. Lucia, 1983, p.81.

[15] Miller, A., ‘Bilin Bilin, King of the Logan’, Albert & Logan News, Sunday 30 May 1993, p.18.

[16] Best, Ysola and Barlow, A., Kombumerri – Saltwater People, Heinemann Australia 1997, p. xi.

.bmp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)