Beagle Bay (1890-2000)

Beagle Bay in the Kimberley commenced as a French Trappist mission in 1890, and was taken on by the German Pallottines in 1901. It became the centre of the Pallottine expansion into the Kimberley and beyond.

- The need for a northern mission

- Selecting a mission site

- Reconnecting with Disaster Bay

- Local politics and tensions

- Fixing a site at Beagle Bay

- Nôtre Dame du Sacré Coeur at Beagle Bay

- The Trappist withdrawal

- The handover to the Pallottines

- The first decade of Sacred Heart Mission

- A new era, 1910

- Dealings with police

- Shadow of War

- The Beagle Bay church

- The inter-war period

- Staff arrivals and growth

- The Moseley Royal Commission in 1934

- Progressing Beagle Bay

- Arrested

- Surveillance and disruption during World War II

- After World War II

- Staff associated with Beagle Bay mission

related entries:

Trappists (forthcoming)

The need for a northern mission

The Catholic reach into the Western Australian pearling belt was instigated by a sudden revival of pearling and a pastoral boom in the Kimberley, and was propelled on the initiative of Fr. Duncan McNab and the newly consecrated Bishop of Perth Matthew Gibney. The latter was anointed in the same year that McNab’s two-year mission at Goodenough Bay (see Disaster Bay) was abandoned (1886). McNab's lobbying in Rome had already resulted in missions in Darwin and the Daly River (see Daly River Missions) and in 1888 Cardinal Patrick Moran reinforced McNab’s appeal in Rome for a greater missionary effort in the far north. Regarding support from the colonial governments, Bishop Dom Rosendo Salvado OSB from New Norcia had warned fellow Catholic administrators in 1881 that 'all they really wanted was that the Aborigines should be kept quiet.'1

From 1882 to 1888 the Kimberley was subject to a massive pastoral land grab. See maps. Moreover, during the 1885/86 season rich new pearl-shell beds had been discovered in Western Australia and fleets of vessels serviced by 'floating stations' (large supply ships) from Thursday Island and Darwin converged on the western Australian coast for the next few years. They were staffed with Filipino, Malay and Japanese workers and sought shelter during 'lay-up' season in the coastal creeks, where their associations with Aboriginal people caused great concern among administrators.

An 1886 Aborigines Protection Act extended the reach of Aboriginal protection legislation over mixed descendants. Western Australia’s Constitution Act 1889 required that 1% of the state’s income, or a minimum of £5,000, be spent on Aboriginal people. With so much public concern and the legal requirement to address it, it was reasonable to expect some solid funding for missions. Premier John Forrest had promised the Bishop 'Government grants in fee simple, and the apportioning of a great reserve for the Kimberley aborigines.'2

The Propaganda Fide invited the French Cistercians based in Sept Fons to commence a northern mission. Sept Fons missionaries were already active in the Pacific, and were suffering from a temporary expulsion of religious orders from France and its territories in the 1880s. Abbot Ambrose Janny returned to France from New Caledonia with a failed Trappist community in 1889. 3 With two siblings at Sept Fons and prior experience in mission leadership in Oceania this 49-year old was an obvious choice. He and Fr. Alphonse Tachon became the Trappist spearhead party arriving in Perth in May 1890 with a promise of ten more missionaries to come to make up the twelve required by Bishop Matthew Gibney who instigated the mission with great personal effort.

Selecting a mission site

Two large reserves had indeed been set aside at Beagle Bay and Disaster Bay, which, according to the Derby pearling masters, was the ‘last land left’ in the Kimberley.4 To select the location of the mission and apply for a lease, Bishop Gibney set out with the two Trappists for what became a four-month long trek of hardship, sickness and endurance. On the boat journey to Derby they stopped at Cossack, Broome and Beagle Bay, and the Bishop observed the pearling industry, which he hoped the missionaries would enter into, the multi-ethnic pearling ports and brothels, and the numerous gang-chained Aboriginal prisoners sentenced to hard labour for stealing sheep. The whole journey is described in Bishop Gibney's diaries. 5

At Derby the government resident and police rendered assistance and assigned constable John Daly and a police tracker to lead them to the two reserves, departing on 4 June 1890. Daly was a local protector of Aborigines and became a cathecist for the new venture, and was subsequently referred to as Brother Xavier. While they were exploring the Dampier Peninsula, Fr. Alphonse Tachon was not well and stayed in Derby to learn Nyul-Nyul while the others undertook a full months’ labourious trekking across the peninsula with some 30-mile rides, always dictated by the need for water. Fr. Ambrose came down with fever and fell off his horse – this was his first horseriding experience - and Bishop Gibney was getting attacks of pain around his lungs and had to sleep as close to the fire as he dared to go – a sorry little group driven by sheer determination.

The Aboriginal tracker also came down with malaria and took the group only as far as McNab’s abandoned mission site. There he retired to his family at Wilgeemun (about 15 miles from Lake Louisa aka Murgullagin, on the inland route between Beagle Bay and Disaster Bay aka Caromel), dropped his uniform and slipped back into traditional life. Meeting him some weeks later Bishop Gibney ‘did not recognize him’. This tracker’s name is not recorded (later on a ‘Sergeant’ Manga appears in Gibney’s diary), but this man's father Jerry Bilarno with his youngest son, aged about 13, came to meet the mission party at Gabarunny well, and at Nullulgulla, about 1 ½ hours ride from Lake Flora, during a twelve-day trek from Derby to Goodenough Bay. These two were the only Aboriginal persons encountered on this whole leg of the journey, though the party often observed fresh tracks, including around their camp in the morning.

On this trek (Derby to Disaster Bay) the exploration party came to the boundary of the reserve land on the Fraser River and were not impressed:

‘We took a circuitous route to note what kind of country is reserved for the natives in this section. I found that we hardly met one acre of good grassland, the only appearance of vegetation on it is spinifex. In all my course from Derby I did not meet any patch of country so bad. As we got out of the Reserve the land improved’.6

At Goodenough Bay people finally showed themselves and Fr. McNab, who had left four years ago, was much remembered and discussed. A large part of the stores was left at Goodenough Bay, and a man called Tommy aka Leidibur from Maddar, south of Fr. McNab’s former mission, became the new guide for the exploration party. Seven young men brought a young woman to the group. The clerics either pretended or really did not understand what it meant. They were heading for Hadley and Hunter’s station 30 miles away to restock on provisions. (This is before Hadley commenced his mission on Sunday Island, and may refer to the pastoral property ‘Lombardina’ which Hunter acquired in 1884 and sold to Gibney in 1892.) At Hunter’s they got fresh salted meat, observed the 60 or so Aborigines working at the station, and the Bishop received a vigorous gum oil rub down for his aching back and shoulder from one of the Aboriginal men: 'I thought he would rub the skin off, but I feel better.'7

After an hour’s ride out of Hunter’s they came to an inlet and had to wait for the tide to recede, which meant an overnight stay outside of an iron shed. Here ten of Hunter’s workers joined them. They brought them fish and offered women for tobacco. In the morning these workers helped the party across the waist-deep creek and ‘a young blackfellow led the way’ six miles to another lagoon and permanent water well where they found three more Aborigines, one of whom took them to the next and only water source, sixteen miles away.

The next day at noon (21 June 1890) they reached Beagle Bay aka Kirmel and four locals visited them in the evening. Two days later they went to Baldwin Creek where they met a group of women and children at the lagoon and another group of twelve women and five children at the creek. They camped five miles above the creek and the men came in the evening for a yarn, saying that most men were turtle-fishing at Lacepede Island on the Governor Weld. One of the young men guided them on a local exploration the next day, and in the evening some men came wanting to trade women for tobacco. Brother Xavier chased them away with such foul language that the Bishop sent them an apology and tobacco the next morning. Two of these men helped the clerics across the creek the next day to reach Brockman’s well in Beagle Bay, where Fr. Ambrose narrowly escaped being bitten by a snake. At the next camp by Wemy pool in Wilgin country the Bishop got sick and was retching in the morning. A local native took them to Warrer pool in Beagle Bay. ‘We found here the largest number of aborigines met with yet, 18 men and 3 boys at one camp.’ They also noted a profusion of wells and springs in the Beagle Bay area, where they spent five days before turning back towards Goodenough Bay (a three-day journey).

On the return journey they camped at ‘Bungua Duck’ (Bungadok about five miles inland from the mission site) and the Bishop obtained information about the strength of the local population:

(28 June 1890) There are 29 men, 39 women and 20 children in this tribe. Berrink [they] called Beagle Bay. (The Bully Bulma called "wheebandur" by whites, a name that stuck among the blacks, has eight wives). The next neighboring tribe, named Mulgin tribe, has 23 men, 15 women, and five children, above Beagle Bay to northward. Winnowel tribe at a creek south of B.B., 15 men, 16 women, seven children (Murrulea), about five miles south. Baldwin Creek, Werragilla native name, 31 men. Our informant could not count the women and children here. Like sheep, he said, and at Carnal Bay [Carnot Bay] they could not be numbered.8

George Goodowel became their guide on the three-day return trip from Beagle Bay to Goodenough Bay:

(28 June 1890) George Goodowel is a most interesting fellow. We made his acquaintance at Kirmel. He looks about 26, and stands 5ft 8in. There was no one to be seen when we camped, but they had already heard of us. When they saw the smoke of our fires they came up in a body. As Tommy, whom we took from Goodenough Bay, did not know the country, George volunteered to come with us. When he arrived "in full dress" he had a shirt and trousers and one stocking, his face shining red, with white stripes from each corner of his mouth in broad lines, then over the top of his nose and from the corners of his eyes, and lastly across his forehead. Each of those ran the full length of his face. He wore a red band round his head at the root of his hair. The hair was all drawn back to form a knob, tightly bound and sticking up from the back of his head; in this was a tuft of feathers. At the root of this knob a flat stick pointed at both ends was stuck in midway. This was George in full dress as he appeared in day and night for three days.

At Wilgeemun they met up with their native police tracker, whom they did not recognize, and presumably he now took over again from Tommy as guide. Two days later, heading for the Fraser River, but missing their target, they reached a clay pan where Fr. Ambrose, wracked by fever again, ‘just lay where he fell’. Next day on the other side of the river, having long run out of Hunters' salt mutton, ‘our native’ shot 10 ducks back in boab tree (garada) country after exactly one month of travelling. They met a Mr. Herbert from Queensland heading for the Ashburton diggings and reached Yeeda Station where Mr. Rose sold them six bullocks at a good price, supplemented by two bullocks donated by Daly, to make up a team.

Next day (4 July 1890) they brought the bullock team into Derby, where they applied for 100,000 acres of land at Beagle Bay (5 July 1890) and held mass ‘at both ends of Derby’ (6 July 1890). One might think that they took a well-earned rest after their month-long trek, but the indefatigable Bishop Gibney was just getting started.

Reconnecting with Disaster Bay

On Monday they loaded up the police cutter (7 July 1890) and on Tuesday poor Fr. Ambrose and Daly set off for Yeeda station with two horses and a foal (and presumably with the bullock team which could not be loaded onto the police cutter). Meanwhile the police cutter loaded up with stores, with ‘a coloured man and a native on board’, took the Bishop and Fr. Alphonse Tachon to Disaster Bay (Caromel), a place rich in crabs, where they held a large feast for the locals dedicated to Our Lady of Mt. Carmel (16 July 1890). Local men kept coming to join the missionary camp at night while the women stayed away, and the old men kept a close watch on pilfering and sent away one boy who stole some biscuits from a tent. Fr. Alphonse Tachon and Bishop Gibney visited the 40-strong men’s camp one night (18 July 1890) just to show that they were not afraid to go unarmed and unaccompanied. The water at Caromel was almost black so the missionaries kept sending for supplies from Wilgoma spring five miles north. The men sailing to Wilgoma also brought pearl-shells with them to trade for tobacco. Some tension surfaced in this trade relationship:

(19 July 1890) We gave them a boilerful of rice and they had plenty of fish. At night they observed a sullen silence. Why I do not know. We have given them no cause, but they are often asking for tobacco and pipes, of which our supply is not large.

Bishop Gibney records the explanation given the next day:

(20 July 1890) Men accounted for their manner last night . When a long absent friend returns all the friends gather round and cry for joy. Some of them went through the ceremony to show us what they did on the return of an old man friend. It is a very affectionate expression of their feelings. We learned later that a relation of the visitor had died in his absence.

It seems that the men performing the odd jobs expected a better welcome and payment. Gibney’s diary does not explain who ‘the visitor’ is - perhaps some news had reached from Beagle Bay about a recent death. The bush telegraph was certainly working well: the crowd at Caromel swelled from 47 to 70 the day before the police cutter arrived with fresh stores and tobacco (23 July 1890). To prepare for a new mission, the members of the missionary party were digging wells and clearing roads, and Fr. Alphonse continued to gather vocabulary. Finally Fr. Ambrose Janny arrived ‘fagged looking’, and Daly arrived at sundown. These two had spent 24 days fighting their way through the bush from Derby to Caromel with the bullock team. ‘All now safe and well at Goodenough Bay.’9

Local politics and tensions

The mission party now had a substantial store of goods at Goodenough Bay. As they were preparing to head off for Beagle Bay in a large group with the bullock team, more tension built:

(4 August 1890) Natives much alarmed because they saw a blackfellow's track they did not know, and one of their women reported having seen a blackfellow fully armed.

The missionaries and their helpers were now laboriously cutting a path for the bullock team and proceeding slowly. On their first day out of Goodneough Bay they had intended for Wedong (or Weedong, which was not yet a cattle station) but couldn’t get through, so went to Danyamung well instead, and finding it dried up, settled for Argomaud. Here they met Tommy (5 August 1890) who had been sent to Beagle Bay to organize two native guides, but he reported that the Beagle Bay people were ‘preparing for war’. ‘Sergeant’ (Manga) feared for his life and went home to Goodenough Bay.

Quite possibly this erratic progress was dictated by local politics. It was after all a question of where the missionaries with their endless supplies were going to settle - on the east or the west coast of the peninsula. It seems that their east coast guides were steering the party to Argomaud rather than Bungadok.

Bishop Gibney wanted to head for Bungadok and started ahead with two helpers (7 August 1890) to clear six or seven miles of a road to Mangul walla (native well), which they had to enlarge to get enough water for the bullocks and horses.

My guides then announced that we could not catch Bunguaduck tonight, but we could get another walla by travelling south. I let them have their way. We walked for two hours more, and when it was quite dark we came on low ground, but no water. We made a fire and camped for the night. I gave them bread and sugar. I had some myself. Thank God, who preserves us all in our ways. With my compass I marked carefully on the ground the way we travelled. They explain distances and direction by lines on the ground. They admitted having missed the way.

Perhaps the Aboriginal guides from the east coast had reason to avoid Bungadok that day, or really tried hard to impede the party’s westward progress. The road clearing party returned to Argomaud to join up with the bullock team to bring it to Mangul (11 August 1890). Fr. Alphonse stayed behind at Argomaud. The Bishop’s road clearing party again went ahead to clear ten more miles of road and camped seven miles short of Bungadok. On 13 August 1890 the bullock team finally came up the four hours from Mangul to Bungadok and the Bishop ‘decided to have the mission hereabouts’. The Goodenough Bay people warned the clerics that there may be a hostile reception because the Beagle Bay people had not come up to meet them. But in the evening a number of the local men came to the camp: no war, no hostile reception, and the missionaries with their supplies were lost to the east coast people who had got on so well with Fr. McNab. It was another seven years before one of the Trappist Fathers was allocated to Disaster Bay mission on the east coast of the peninsula.

Fixing a site at Beagle Bay

In the morning (14 August 1890) ‘Caley’ showed the Bishop and Fr. Ambrose Janny around for six hours to fix on a site, and they selected a place near Nullin, eight miles from Bungadok and seven miles from Kirmel (Beagle Bay), ‘3 miles east of 44th’ (this cannot refer to latitude - it is more likely the identification of an explorer's camp, perhaps their own prior camp).

Both clerics got bogged in the swamp at different times, and Fr. Ambrose had another attack of fever and diarrhea (16, 17, 18 August). Had Fr. Ambrose been looking for signs he might have concluded that this was not meant as his place – the last time they were in the Beagle Bay area he had a close encounter with a snake and the Bishop was retching. But the Bishop read different signs and on 20 August, the Feast of St. Bernard, he dedicated the mission to St. Bernard, principal patron of the Trappists. ‘Thank God this mission is now a fact; no more place for doubt’ he wrote, somewhat precipitously.

After nine days at Nullin they headed back for the sweet water of Wilgoma. It had taken ten days to cross the peninsula with the bullock team, but the return trip to Goodenough Bay, now on tracks that had been cleared, only took two days, Daly with the bullock team hard on their heels. The stores at Goodenough Bay were perfectly safe. ‘The native Manga (Sergeant), whom we took with us, told us that an old man found a boy go into the tent, and he nearly killed him.’10

The Bishop was not yet finished. He undertook a third voyage to the other side of the peninsula, via Wilgoma and Argomaud with eight men, the women and children following at a distance. ‘Father Ambrose tells me he has got the names of 60 natives resident in Yemarang alone.’ At the end of August they were back at Nullin, their new mission site.

‘the procession was such a one as is seldom seen except in those parts. We are not very presentable ourselves, but our acquaintances and neighbours are not particular. One of our black men had a trousers on him. Another had a hat and shirt; another a hat; and several had helmets of feathers and plumes of feathers tied to their arms above the elbow, while some were not troubled with any of these extras. We reached the place early, and settled down for the night.’11

Several more trips were made back and forth across Dampier peninsula to relocate the stores from Goodenough Bay to Nullin:

‘The poor fellow who was in charge [of the stores at Goodenough Bay] cleared out the same night after we came, as we conjecture lest we would have any cause to find fault with him. I was sorry for this, as I should like to have rewarded him for his fidelity.’

On the sea journey from Perth Bishop Gibney had noted the crops that were thriving on different stations and had sent an order to the Hanoverian botanist Maurice Holtze, government gardner at Port Darwin, for ‘seeds and plants of pineapples, bananas, chillies, potatoes, yams, pomegranates, rice, pawpaws, so that the Mission garden can be started, by him’.12 They now cleared land for the mission gardens.

And then the bombshell:

(1 September 1890) 'Father Abbot took me by surprise when he told me to-day that he did not know whether they would remain on this mission. He had written fully to their Abbot at Sept Fons, and he says it will depend on his answer. I do not understand them.'

Bishop Gibney put the hard word on the two Trappists and required a firm commitment at once. Fr. Ambrose Janny, who had already seen a Trappist community fail in New Caledonia, conceded, according to Gibney:

(1 September 1890) ‘if I [Gibney] thought it was the will of God they would do so. My belief was fixed, so we early settled the matter. He [Ambrose] expressed his fears about the means of support until the ground began to produce. My answer was: God will provide, and I will not see you hungry.

(8 September 1890) 'Thank God we are settled; my work is done.’

On 10 September 1890 Daly conducted the Bishop on a three-day horseride, partly along the beach, back to Broome where the Bishop boarded the Meda to Perth.

Nôtre Dame du Sacré Coeur at Beagle Bay

Bishop Gibney had stipulated a minimum of twelve staff to fulfill the conditions of the lease for the Trappist mission at Beagle Bay called ‘Nôtre Dame du Sacré Coeur’ (Our Lady of the Sacred Heart). Sept Fons sent 18 staff altogether – two in 1890, six more in 1892 and another ten in 1895. The first fatality was in January 1896 with the drowning of Br. Francis.13

The only one of these eighteen remembered in Australia is the Spanish-speaking Fr. Nicholas Emo. He was designated to remain in Broome to minister to up to 300 Spanish-speaking Filipinos engaged in pearling and fishing, and he remained in the Kimberley after the Trappist retreat. Fr. Emo recorded his arrival journey in his 1895 diary. The party was led by Abbot Ambrose Janny and included his younger brother Jean-Marie Janny, both brothers of the prior of Sept Fons, Felix Janny. They took the Salazie to Singapore occupying two cabins of six berths each, and from there took the British Australind on 30 March 1895, and rendevouzed with the mission lugger Jessie at the Lacepede Islands on 8 April 1895. They arrived at the Beagle Bay beach at 11 pm and walked through the sand and mud for 14 km arriving at the mission at 4 am.14

These Trappists were mostly in their forties and fifties, and tried to maintain the daily and yearly rhythms of their home. They fasted at Lent when it was actually time for harvest, and the strict Trappist daily rhythm gave equal time to working and praying. They finished building their monastery in November 1893 and chanted through the Kimberley night from 2am to 6am and at various times during the day.

2.00 am rise, Office and meditation

3.00 brothers go milking, Fathers continue chanting Office

4.00 Mass

4.30 Fathers chant Office, Brothers work

6.00 breakfast

6.30 work (4 hrs)

10.30 visit the Blessed Sacrament, reading in Chapter

12.00 Angelus

Dinner

siesta

2.00 pm chanting Office

2.30 work (3.5 hrs)

6.00 mediation

Quarter Hour

Supper

pious lecture in Chapel

Compline (Night Prayers)

Examen in Church

Salve

Angelus

8.00 pm to Rest

The Trappist emphasis on ritual and chanting must have been immediately resonant to Aboriginal people, but this was clearly not a sustainable schedule. A visiting journalist in late 1896 commented on the monastic lifestyle at the mission: 'the religious observances of the Order are carried out with as much completeness as if the monastery were situated in the centre of a Catholic country', but the religious observances had already been adjusted, and the evening prayers consisted of a rosary in the chapel. Aboriginal altar boys dressed in red served at the daily morning mass, and the missionaries conducted a daily school for children and instruction for adults. On Sundays Father Alphonse preached in Nyul-Nyul to an attentive congregation, women sitting on one side and men on the other as in the European Catholic churches, but if he was denouncing some indigenous custom an Elder might stand up and begin to argue vigorously. 15

The journalist had been invited to witness the first adult baptisms. Fr. Alphonse Tachon had corresponded with Fr. Duncan McNab (who was now living with Jesuits in Richmond, Victoria) on the question of polygamy as an impediment for baptism. With McNab's encouragement he gathered the first twelve converts for a mass baptism on the Feast of Assumption of Our Lady, 15 August 1896. Several of them were named after the Trappist Brothers and Fathers: ‘Joachim’ Friday (born 1870 – age 26), ‘Joseph’ Santamara (born 1874 - age 22), ‘Jacques’ Tiarbarbar (born 1875), Edmund Palelbo (1876), Patrick Wardiebor (1876), Louis Wanaregne (1879), Remi Balagai (1883 – age 13), ‘Sebastian’ Kalkokarbar (1885), ‘Narcisse’ Wanaregne, Pierre Telediel, Malgen and Leon Palsmorebon.16 The following year 23 people were baptized.17

The Trappists kept out of public gaze during their ten years in the Kimberley. Half of their funding came from the Propaganda Fide and the Trappist Order, about 20% from the state government, and only 10% from donations (see Trappist Budget). They laid the foundation for language work in the Kimberley. Fr. Marie Bernard wrote that ‘One of our Fathers produced a grammar, vocabulary and a catechism in an Aboriginal language’18. Fr. Nicholas Emo in Broome compiled a Yawuru/Spanish dictionary and Fr. Alphonse Tachon at Beagle Bay was working on the Nyul-Nyul language. For this work they needed to work closely with Aboriginal people. McNab’s former assistant, a man referred to as ‘Knife’, lived at nearby Boolgin to an old age and may have helped to facilitate the success of the Trappists.19 Felix Gnodonbor taught Fr. Alphonse Nyul-Nyul and helped him to translate key concepts. He became instrumental in the acceptance of the Christian missionaries at Beagle Bay. His nephew Remi was among the first to be baptized in August 1896, and Felix himself was baptized the following year with Thomas Puertollano as Godfather. Felix, named like the brother of Fr. Ambrose and Fr. Jean-Marie, remained on the mission with his wife Madeleine until 1931.20 In 1896 he said:

I have given my son [Remi] to you. You have baptized him. I am happy about it. He will be happy, mind him. Me too, I want to be happy. In two months I will turn away again all my wives and will keep only one of them, you will baptize me, for I say it to you, I want to be a Christian.21

Two of Felix Gnodonbor’s nieces, Leonie Widgie and Fidelis Elizabeth Victor became early converts, and one of Felix’s granddaughters, Magdalene Williams, later helped to found Balgo and LaGrange missions.22 Remy [sic] Balagai told Fr. Francis Hügel that when he was a senior boy his father brought him to the mission. The first time he stayed in the camp with ‘the entire mob’ and only attended school, which was conducted in French, the second time he was invited into the dormitory. When the old men decided that a boy was ready they would come into the mission, painted up in red and white, to fetch them for ‘Malulu’ (initiation). Fr. Alphonse Tachon tried to convince Remi’s father that this custom needed to be stopped, but the old men would not give up their law, and invited the priest to attend a ceremony to see for himself. 23

New Norcia was then the only other religious mission in Western Australia. The Trappists estimated that in ten years their three stations ministered to about 900 people and that they baptized at least 200 people who had relinquished polygamy and given up contact with pearlers, and attended mass and Holy Communion. 24 They acquired a 10,000-acre lease in addition to the 700,000-acre native reserve, and erected a monastery consisting of three long buildings, a kitchen, a sawmill, workshops and other iron-roofed outhouses. Over ten years funding amounted to £7,500 derived from the Aborigines Board (£2,185), the Catholic Church (Cardinal Moran £1,500, Propaganda Fide £1,600, Cistercians £3,250) and public donations £1,000.25 The missionaries offered food for work and made vegetable and fruit gardens and extended their herds from 150 to about 600 or 700 cattle and and equal number of sheep.

An 1898 cyclone destroyed some of the buildings at Beagle Bay, and several of the padres were battling with sickness, but otherwise there was every promise of success. 26 All the more surprising it seemed that in 1900 the Trappists decided to abandon the Kimberley mission. Their withdrawal seems like a disorganized debacle that the Trappists later sought to explain.

The Trappist withdrawal

The mission began to fall apart after Dom Ambrose Janny resigned as superior. He had long felt too ill to continue and when he was at Sept Fons in 1895 to recruit the second consignment of missionaries he actually wanted to stay behind. In 1897 he finally left the Kimberley, around age 57. Fr. Anselm Lenegre became his replacement but was found to be ‘too condescending’27 and in June 1899 Fr. Alphonse Tachon was elected superior. Tachon did not want to assume his duties until he was confirmed by the Generalate in Rome, which took another few months. As soon as he was formally appointed Fr. Tachon went to Perth to see about securing the title to the mission land. Daisy Bates found him ‘terriby emaciated, nearly blind and trembling with the feebleness of old age’.28

By this time dissent had set in to such a degree that Frs. Ermenfroi Nachin and Bernard de Louarn returned to Sept Fons in July 1899. Fr. Jean Baptiste Chautard had just been elected as new Abbott of Sept Fons and his first administrative act became the winding down of Beagle Bay mission at the advice of the two returned missionaries. Fr. Emo, too, reported from Broome that ‘Beagle Bay is very confused, Reverend Father, one cannot visit it without being very uncomfortable’. Emo mentioned that a letter from the Superior General had shamed Fr. Jean-Marie Janny and Br. Narcisse Janne at Disaster Bay for their ‘special relationship’ and Emo also commented on ‘too natural a mutual attachment between these two Fathers (and it is not only me who appears to notice it)’.29

In December 1899 the Abbott sent orders to Emo to prepare for partial withdrawal from the Beagle Bay mission, but not to make this public so as not to disadvantage the sale of property (and perhaps there were unstated reasons for secrecy as well). Beagle Bay was to be conducted as a grange (without an Abbot) on reduced staff and supervised by Emo. This greatly embarrassed Fr. Alphonse and Bishop Gibney who were in Perth planning to extend the mission. These two were trying to raise more funds and secure the title over the mission land, and Bishop Gibney commissioned three boats for the mission and was planning to visit the mission with his assistant Dean Martelli. Neither of them had been told that the mission was getting wound down. Emo later recounted how he waited for four days at sea to reconnoiter with the passenger ship carrying the Bishop, but inexplicably – guided no doubt by an invisible hand30 - failed to meet the ship so that Gibney’s visit did not come about. In fact the mission was in an extreme state of turmoil. Emo as Acting Superior of Beagle Bay dismissed the children, and stopped the women going into the rooms. He locked away the wine and other provisions, and started to sell cattle to finance the homeward passages of the staff.31 He was clearly in a high state of agitation and wrote streams of letters to Sept Fons explaining and defending himself.

The other Trappists at Beagle Bay resented giving up the mission: ‘all the spirits are not docile’.32 Fr. Jean-Marie Janny was so angry that he said he wanted to claim back the 150,000 Francs that he gave to his order on joining. Emo wrote that Janny would ‘rather die than return to Sept Fons’, and that he was gripped by a mood of defiance, being ‘accustomed to be free and independent in his nest [at Disaster Bay]’.33 There were strong feelings at the mission as Emo continued to liquidate its assets. When Emo wanted to sell the statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary, one of the Fathers showed his disagreement ‘in terms too strong for Religious’, ‘causing a scandal in the presence of the blacks and the brothers’. Emo had found a buyer for the statue, a ‘rich Japanese lady’ in Broome, but when he got there she had died:

‘Evidently there is a superior force that, come what may, prevents the liquidation [of Beagle Bay mission] and which, joined to the piety of our Blacks, has convinced me that God is watching over their lot.’34

In March 1900 the residence of the absent Fr. Alphonse, which also served as the school, burned down. A cyclone had already blown down the refectory and outbuildings, now only the church, the dormitory and the kitchen were left standing. Emo supplied the explanation that it was due to the ‘imprudence of a woman who was smoking a pipe too close to the dry bark’. 35 Harris suspects the Trappists burned down the buildings in anger.36

Fr. Ermenfroi Nachin unexpectedly returned from Sept Fons to Beagle Bay with money for passages just as Fr. Emo was preparing to send some missionaries home, and in April 1900 eight staff were sent off to the Trappist monastery of El Athroun in Palestine. According to Fr. Marie Bernard (who had never been there), the Aboriginal residents were crying ‘fathers, stay, don’t leave us. Who will give us the sacraments when we die? Do you want us to die like kangaroos?37

By June 1900 news of the wind-down had reached Perth and Emo decided to also send Brs. Joseph and Bonaventure away. Br. Bonaventure Holthurin, a young Dutch tailor later went to Maristella in Brazil. Br. Joseph a shepherd, had arrived from Rome in 1892 and disappears from the record.38 Emo wrote that these two

'are in imminent danger of losing their vocation if they are not removed straight away from Australia fearing on the other hand some scandal may compromise the honour of our holy Order …. it would be indiscreet to put to paper the motives which have confirmed my conviction.'39

'As for Br. Bonaventure, he was always surrounded by young girls and little girls who used to go into his room for tobacco (which is very dear here) because they brought him little lizards for his birds, and he was always going with them in a way that made me anxious. (Sometimes I would see him coming alone in the dark from the garden.) I was afraid in case he was assailed also by some great temptation.

He gave everything to the blacks – it was impossible to prevent him for he always had too much liberty; and before he left, without permission from anyone, he gave almost every piece of linen and material, trousers and shirts from the Dressing Room with all the cotton and needles, to the blackfellows, …. wooden containers full or rice were carried each day to the camp for the dogs’.40

One of the Brothers was suffering from venereal disease and Emo was reluctant to have him treated in Broome for fear of gossip.

'I was obliged to tell him “Brother, I don’t want you going into the bush because it’s not good for you; please stay in the house until your departure” - he flew into such a tantrum that he flung himself into my room pale as a corpse, shouting so loudly and so upset that I was quite surprised. Unhappily we had a visitor (white) that day who at that moment was only 50 steps from the front door. … [He said that] he was not going to El Athroun, he wanted to stay in Broome with the policeman (his compatriot) and that he was going to let the Brothers know everything that had happened at the mission etc. etc. and the public would judge afterwards. … I knelt before him a long time to calm him down and clasped his feet.'41

Emo did not trust these two to return to Sept Fons, because they ‘are too attached to Australia’, so, in an 80-page letter defending his actions, he wrote that he ‘sacrificed’ the carpenter Br. Etienne Pidat to accompany them, keeping ‘only three indispensible brothers’. 42 In repatriating practically all the French Brothers Emo went further than intended by Sept Fons.

Bishop Gibney had by now placed an injunction on the sale of cattle from the mission and initiated negotiations with the German Pallottines.43 He came on a visit of inspection on 17 August 1900 (see below by Daisy Bates) just after Emo had sent the remaining French missionaries away, and only Fr. Ermenfroi Nachin was still in the Kimberley. Nachin had told Fr. Joachim O'Dwyer that he had been sent back to the Kimberley to 'keep an eye' on Emo. Engineered no doubt by Emo, Nachin 'kept out of sight' and left for Palestine during Bishop Gibney’s visit to the Kimberley.

'Fr. Ermenfroi [Nachin] … had the bad habit of sometimes wanting to chase the blacks, grabbing a stick, chasing the children with a loaded gun charged only with powder, and even with flour; which spurts out immediately and led to much trouble and he had to hide it with the arrival of the Bishop who would have given him a good lesson, for if the papers caused such an uproar because on one station a protestant had hit a blackfellow with his stick, ... [this] ... would have been a disgrace for us.'44

Emo claimed that Nachin had come back to Beagle Bay like a choleric, got drunk, swore, and called the Australian bishops ‘pirates’. Emo’s final comment on the ‘unpopular’ Fr. Ermenfroi was that ‘all the black women left soon after he arrived’ and that he had been on the point of being dragged to the courts’ for chasing away the children with poweder-charged gunshots. ‘He compromised the good name of the mission’. ‘We can say nobody liked him and all complained of him.’45

|

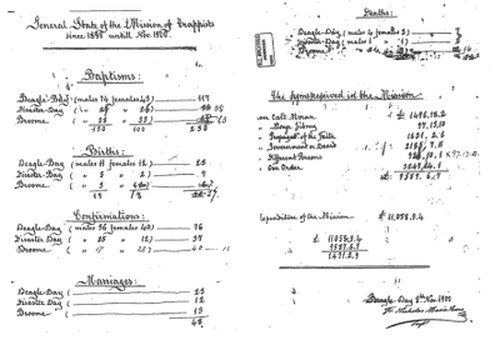

| General State of the Mission of Trappists since 1890 until November 1900

Source: Nailon 2005 (II):143. |

Fr. Emo drew up a balance sheet showing that the Trappist mission had cost some £11,000 in ten years, of which just over £2,000 had come from the government and with a funding shortfall of nearly £1,500. The Trappists had performed 255 baptisms, 153 confirmations, and 48 marriages, and recorded 37 births and 23 deaths in Broome, Disaster Bay and Beagle Bay.

The handover to the Pallottines

The Trappist retreat from the Kimberley had been engineered 'from below' and surprised the Generalate at Sept Fons as much as the Australian bishops. In the change of guard from the Trappists to the Pallottines practically everyone felt sidelined. Fr. Marie Bernard, describing the mission to the Limburg Pallottine Generalate in preparation for a sale, explained that the French padres had been recalled because they were too few in number and distributed over three stations (Beagle Bay, Disaster Bay and Broome), and therefore ‘unable to engage in the community life that is so central to our order’, and the mission had never received a visitation in its ten years of existence because of its isolation.46 All of this was true, but it hardly described the turmoil and difficulties at the mission. It was the explanation agreed on after Bishop Gibney saw for himself the state of affairs in the Kimberley. 47

The Abbot of Sept Fons, Dom Jean Baptiste Chautard, followed up with a letter to Bishop Gibney apologizing for the hasty retreat and lack of consultation. The subsidies had not been enough to run the mission, and Abbot Chautard had meant to scale down the mission to six or eight staff, but events had overtaken his deliberations. He had been waiting, since mid-1900, for a visit from Bishop William Bernard Kelly (Bishop of Geraldton 1898-1921), who was expected to call in at Sept Fons, when the Abbot at Beagle Bay (presumably Alphonse Tachon) decided to return to France. Abbot Chautard recapitulated how Fr. Nicholas Emo was left in charge of the mission and more staff went home, leaving all but Fr. Nicholas and the two local Brothers, Br. Xavier and Br. John.48

Bishop Kelly was visiting Rome when he received the news of the Trappist departure around October 1900, and at once invited the Pallottines to take over. When the Pallottines asked for information about the mission in November 1900, Abbot Chautard at Sept Fons was ‘surprised’ at this take-over:

'Two months ago, the Pallottine Fathers of Rome asked me for some information that I hastened to give them, and I was surprised to learn that three weeks before, Bishop Kelly had arranged with them, and they were going to leave for Broome without delay. All therefore is terminated for us.' 49

The Cistercians describing the state of the mission omitted that since a Chief Protector of Aborigines had been appointed in 1897 the tide had turned against the mission. The Western Australian government overrode the constitutional requirements of the 1889 Constitution Act by forming its own Aboriginal Department under a Chief Protector of Aborigines, Harry Prinsep, assisted by a travelling inspector. Funding for Beagle Bay mission was stopped.

It is very likely that the Trappists’ close collaboration with the mixed Latino/Aboriginal communities in Broome, at Beagle Bay and at Disaster Bay earned them the cold shoulder of the Chief Protector. The 1898 Western Australian Land Act provided that land may be granted or leased to Aborigines, and the Trappists had hoped to parcel out land to the Filipino/Aboriginal resident families. However the government aborted this idea by delaying the lease appraisal that should have made the Trappists eligible for freehold land.50 The government had now broken all its promises: no ‘land in fee simple’ and no financial support.

Fr. Marie Bernard of Sept Fons wrote a glowing report of the Beagle Bay mission and its potential based on hearsay from ‘one of the padres who had returned’. He described its excellent location, with connection from Broome to Singapore by English and Australian companies, and Broome connected with the Australian capitals. It had many permanent springs and a healthy climate (although afflictions of the eye might beset newcomers). The lease could support thousands of cattle and, if fenced, 5,000 sheep, and had the potential to earn a lot of money from cattle and agriculture. It was suitable for large-scale plantation of pineapple, tobacco, bananas, maybe grapevines, but certainly vegetables such as potatoes, pumpkin, sweet potato, cassava, some types of beans and taro. Sorghum and durum was in much demand and grew there as well as wheat does in France. Rice would also flourish. There was never any hail, only a two-or three months raining season when flooding and bogging occurs and ‘one cannot go about’. The mission could also profitably engage in pearling, a work that would please the Aborigines and Manilamen. Some language work had already been accomplished by the Trappist padres, which they had given to Bishop Kelly to take back to Australia. The Aborigines were ‘not nearly as wild’ as those further north, and they no longer engaged in bloody revenge although still held corroborees where they drank blood and held dances. There was no theft [!]or robbery. To civilize them would require schooling and work, something that the government would liberally fund, and the government would easily approve another 100,000 acres if requested. Since the mission was fully established with buildings, gardens and tools, and was self-supporting in food production, it would not require much money, and would be well supported by the government, as well as the cardinal and bishops – who would no doubt support the idea of erecting the Kimberley into a vicariate, just like New Norcia. Indeed, there was no resistance from any quarter to this mission, and it would also be supported by foreigners and by the natives, who already attended church and knew their prayers. It would be left to the Pallottines for a small price, apparently the Abbot even thought of leaving all the chattels free of charge. Two or three missionaries would suffice - indeed at the time of writing just one was doing all the work by himself. Read in German

In fact Fr. Emo had the help of Br. Xavier, Br. John, and Sebastian Damaso, so it hardly amounted to one missionary doing all the work by himself. According to Emo, the Filipinos were doing most of the work at Beagle Bay.51 Four Filipino families were established in substantial dwellings on the mission, and the miraculous transformation of blood-drinking corroboree dancers to prayerful workers as described, must have owed very much to these mixed Aboriginal families. Bishop Gibney observed that at Beagle Bay the birth rate exceeded deaths52 and most likely this unusual trend also reflects the presence of these mixed families.

There followed tense negotiations, the execution of which fell largely to Fr. Emo acting for the Trappists. Bishop Gibney had a contract of sale for the cattle drawn up and when Fr. Emo refused to sign on behalf of the Trappists, the Bishop shouted at him in the Magistrate’s court.53 The Trappists had run up a debit balance of £1,471, and wanted to recover some funds for their establishment in Palestine. They estimated their improvements to be worth £10,000 (double what was required under the lease conditions).54 However, this value to the mission had mostly been added by Aboriginal work and was not for the Trappists to sell. Commissioner Dr. Walter Roth recapitulated in 1905:

'When the Trappists first arrived in the State in 1895 [sic] they brought a little money out with them, and with this they purchased about 150 head of cattle. When the Order took its departure in 1901 and was replaced by the Pallottines, Father Nicholas [Emo], under power of attorney from his superior, only sold Bishop Gibney the cattle, which had by that time increased to 800. The price to be paid was £2,640. [This figure does not include the property in Broome.] Father Nicholas did not feel justified in selling the buildings, fences, improvements, etc, because he considered them to be part and parcel of the trust. They had been built with the labour and assistance of the blacks, and they had been erected for the use and benefit of the natives.'55

Bishop Gibney continued to take a strong and hands-on interest in the continuation of this mission. The church had leased a 100,000-acre portion of land adjacent to the Aboriginal reserve at Beagle Bay, of which 10,000 acres were up for freehold on the condition that a minimum amount of improvements were effected.56 The review of this lease had been denied the Trappists. While the handover of Beagle Bay was underway, 65-year old Bishop Gibney took it upon himself to inspect the mission stations with Dean Luigi Martelli and Daisy Bates. Daisy Bates, writing a series of reports of the Australasian and Journal of Agriculture made the most of her little adventure in northern Australia. Read more

Daisy Bates, Reminiscences of a visit to Beagle Bay, Disaster Bay and Broome, August/September 1900 (Summary)

The resolute Irish woman Daisy Bates had met Dean Luigi Martelli on his journey to Australia in 1881 and Bates used this connection to meet the Irish Bishop Matthew Gibney and persuaded him to allow her to accompany them to the north on a three-months tour of inspection to the Kimberley mission commencing on 17 August 1900. According to her account, Fr. Emo and skipper Filomeno Rodriguez met them in Broome and took them to Beagle Bay on the latter's Sree Pas Sair, a former luxury yacht now run down from years of pearling. Fr. Emo explained that church law forbade a woman at the monastery unless she was a queen or the wife or a head of state.57 Bates spoke to him in French, paid attention and agreed with him on every point and charmed him in every way until he allowed her the use of his room in the Broome ‘monastery’, containing a bag bed with seaweed pillow and a tree stump for a table. At Beagle Bay they found the community hall burnt down and the place in decay and disrepair. Their task was to value every single item in order to estimate the improvements according to the conditions of the lease, so they repaired as much as they could. The priests (Gibney, Martelli, Emo) were in charge of the men repairing fences and straightening out buildings, while Bates and the women weeded the gardens and cleaned out the wells. The Bishop helped to dig wells and took off with a compass and ship’s chain to survey the boundaries. Daisy Bates and a small group accompanied him:

‘We were always hungry. Brother Xavier … would forget the salt or the bread or the meat, or the place where he had arranged to meet us, or that we existed at all. … On the night walkings, rosaries were chanted all the way home, the natives and brothers responding. I often stumbled and fell in the dark but that rosary never stopped.’58

Bates offered her own vast cultural repertoire to enliven the spirits, mostly perhaps her own, by singing ring-a-ring-a-rosy while the women weeded, and entertained the Bishop with ‘Thro’ hedges and ditches I tore me auld britches, for you Maryanne, for you Maryanne’. She took every opportunity to tease the Bishop, who paid back in equal currency when Bates cooked a dinner and he suggested it should be put under a glass case as a lesson in what not to do. Bates was not the only joker in the party. Not long after the Bishop held a mass baptism at Beagle Bay garbed in full ceremonial purple and anointing each candidate with the papal blessing and the Pax Tecum with a little blow on the cheek, one of the corroborree dancers, Goodowel, was observed with a red-ochred billycan over his head, lining up his audience to give each one a little smack on the ear with the words ‘Bags tak’em’.59

The Bishop's party left Perth on 17 August 1900 and spent three months at the three Kimberley stations to put the missions in order for the handover and government valuation. As the government had instructed its surveyor not to proceed with the survey, the Bishop forced the issue by organising his own survey party and went public over the State government's non-cooperation. Read more. Gibney’s press release resulted in a telegram from the Chief Protector informing Fr. Emo that the mission was to receive £250 per annum.60 An Irish priest from Cossack (presumably Fr. Joachim O'Dwyer) was stationed at Beagle Bay to await the arrival of the Pallottines, and if for some reason the handover should not eventuate, the German Pallottines would be posted instead to the Daly River Missions, which the Austrian Jesuits had just abandoned.61

Eventually the government surveyor agreed that the value of improvements on the Trappist lease was £6,000. This was understood to satisfy the lease requirements so the lease could be secured. According to Daisy Bates this happened while she and Bishop Gibney were still there, and ‘in jubilation’ they at once made some mud bricks, and she herself laid the foundation stone for a convent. 62 But freehold land was not granted. Dr. Walter Roth reported in 1905:

'On inquiry from Father Walter, the present official head of the mission, the improvements on which this sum of money [the value of improvements] has been expended are in the main on Dampier Location No. 6 - at any rate, certainly not on the total reservation, as required by the conditions. This location is one of the four (Nos. 5, 6, 7, 8) which the mission is anxious to obtain in fee simple, and practically the only four on the reserve where there would appear to be permanent water. …

Your Commissioner recommends that the Lands Department, when issuing the title to the lands in question, will protect the interests of the aborigines, and take care that the property held in trust for them is not handed over to the mission.'63 Read more

Dr. Walter Roth, Chief Protector of Aborigines in Queensland, and Royal Commissioner of Inquiry into the Condition of Natives in Western Australia, did not hold a high opinion of the first Western Australian Chief Protector. Roth found that Prinsep was unable to supply reliable information about government funding for missions. Bishop Gibney shared this opinion and accused ‘so-called Protector’ Prinsep of starving the mission of funds that were lawfully designated for Aboriginal people.

The first decade of Sacred Heart Mission

The Beagle Bay mission was officially committed to the Pious Society of Missions (Pallottines) on 12 January 1901. In April 1901 the first German Pallottines arrived - Fr. Georg Walter, with experience in Cameroon, as mission superior, one of his former students, Fr. Patrick White from London, and the Brothers August Sixt and Matthias Kasparek from Limburg.

.jpg) |

|

The first Pallottine consignment at Beagle Bay Source: G. Walter Australien - Land, Leute, Mission, 1928:137. |

The Pallottines purchased the cattle along with the property in Broome for £3,740 to be paid within five years.64 Meanwhile Fr. Jean-Marie Janny had returned to Australia and ‘watched Fr. Walter like a hawk’.65 Janny now placed a further injunction on the sale of cattle until the Trappists received their first instalment of £1,00066, so Bishop Gibney took out a mortgage of £1,200 at 6% interest67 and the Pallottine mission was steeped in impossible debt for many years. Fr. Janny also took over the Broome properties that Emo considered 'his', since the church and residence had been built with funding and volunteer labour from his Broome Filipino congregation, and had been included in the sale. Fr. Emo started afresh at 'The Point', a fringe settlement in Broome.

At Beagle Bay Fr. White recommenced the school and the two Pallottine Brothers and mission children set to work making 25,000 mud bricks, which were destroyed by torrential rains in 1901. In 1902, with everyone still accommodated in paper bark huts, the mission was hit by a storm. 68 Beagle Bay needed more staff and more money.

Being so short-staffed Fr. Walter was happy to allow Fr. Emo to continue on in Broome, and initially counted both Emo and Jean-Marie Janny officially among his staff. As Walter was about to depart for Germany, Bishop Gibney sternly reminded him that the 10,000 acre lease in fee simple carried the condition that the mission would be staffed with a minimum of twelve:

Now, unless your Order is prepared to have a community of twelve men at least at Beagle Bay I shall be compelled to take the Mission from you and place it in the hands of others who will be only too glad to fulfil the conditions I entered into with the civil authorities.69

A second consignment of three Brothers and a Father arrived in December 1902 - Fr. Heinrich Rensmann (age 27), Br. Bernhard Hoffmann (age 30), Br. Johann Graf (age 29) and Br. Rudolf Zach (age 32). Even counting in Fr. Emo and Fr. Jean-Marie Janny, they were still short of the apostolic number, and neither Janny nor White, nor indeed Walter or Emo, intended staying at Beagle Bay. Fr. Patrick White withdrew from Beagle Bay and focused instead on the Catholic populations in Broome, Derby and later in Perth, and on fundraising in the Australian capitals before returning to Britain. Fr. Walter also left for Europe to recruit more staff.

Fr. Walter returned from Germany around March 1903 with three more Brothers, Wollseifer, Labonte and Wesely, so the mission now had a carpenter, a shoemaker, a bricklayer, a blacksmith and three farmers. The cattle herd increased from about 800 head to 1,800 head of cattle and 150 pigs, and they employed about 25 indigenous people at 20s per month. The shortfall in funding and their mounting debts forced them to generate income.

The new priest at the mission, Fr. Rensmann, only took a few months before he was able to preach and give lessons in Nyul-Nyul and sang hymns in Nyul-Nyul with adults and children. 70 He was in charge of the school, teaching Catechism on Sundays and delivering the sermon once a fortnight. After half a year, by May 1903, he was in the process of preparing several women and children for baptism. Fr. Rensmann was confident about the mission and wrote to Limburg that cattle and sawmilling earned several thousand Marks each annually and the gardens also produced well.71

In the first few years they were spending over £900 per annum. 72 In 1903 the chapel burned down and the mission boat Diamond was wrecked at Sandy Point73 adding to their already significant debts. They now decided to enter into pearl-shelling with a mission-owned lugger, as both Bishop Gibney and the Trappists had suggested. A ten-year contract was drawn up for the advance of 10,000 Lire between Max Kugelmann, Provincial at Limburg acting for the Pallotines, and his brother Justizrat (QC) Dr. Kugelmann, Dr. Otto Wassermann QC, and Kommerzienrat (councilor of commerce) Franz Wasserman for a half share of the net profits payable each May, and 10% depreciation per annum.74 They commissioned Hyman and Anderson in Broome75 to build the Leo and the Pio, the latter named after Pope Pius X, elected in August 1903. Alas, the prices for shell went down that year and they ended up with a loss. By 1909 Fr. Bischofs referred to a mortage of £2,000 at 5% interest, so the debts of the mission were mounting.76

The State govenment had started to remove children to the mission and from May 1903 the government subsidy was increased from £185 to £250 per annum based on a one-shilling-per-person formula. Lawrence Clark was one of five boys removed from Broome to Beagle Bay Mission (on the Pio on 10 August 1904) along with Vincent, John, and Paddy Djagween. He remembered that there were no Sisters and only a few girls on the mission, and Br. Sixt was the chief cook, always supervising six boys in the kitchen, rising at 5am. Victor Tieldiel was one them, doing French cooking with Br. Sixt and Br. Labonte.77

Fr. Rensmann described the Pallottine daily mission routine78 with less chanting, praying, and contemplation, and more time to sleep than the Trappists:

5.15 rise

5.30 contemplation

6.00 mass

6.30 breakfast

7.15 work

9.30 refreshment, then work

11.30 end of morning work

11.45 contemplation, lunch, rest or relaxation

14.30 visitation, then 4 hours work

17.30 end of afternoon work

18.00 rosary etc.

20.30 spiritual reading [Alonso Rodriguez, The Practice of Christian Perfection, 1609]

21.00 retire

They were still short of the required apostolic number, and there were still not enough Pallottine staff to run the mission. Fr. Janny was either at Disaster Bay or Lombadina, Fr. Emo was in Broome, Fr. White had moved to Broome, and Fr. Walter had also stationed himself in Broome. Fr. Rensmann was the only priest on the mission supervising eight Brothers and the day-to-day running of the mission. In January 1904 Fr. Rensmann died of a heart attack while swimming in the creek with Br. Wollseifer. Visiting Beagle Bay in February 1904 Constable Cunningham found Fr. White and a Fr. Russell at the mission.79 Fr. Russell must have been a diocesan priest from Broome presumably sent by Bishop Kelly of Geraldton to temporarily replace Fr. Rensmann80, but to run the school they now had to employ a secular teacher, Mr. Randle.

When Fr. Walter moved to Broome relations between him and Fr. Emo soured quickly. Emo continued to marry Filipino and Asian men with Aboriginal women and Walter wanted to replace Emo with a Pallottine presence in Broome (himself and Fr. White). Walter asked for more Pallottine priests for Beagle Bay, but only four more Brothers arrived in May 1904, Heinrich Krallmann, Franz Stütting, Alfons Herrmann and Anton Helmprecht. Enough Pallottines were now in the Kimberley to let Fr. Emo go, but there were still not enough priests.

In October 1904 Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Condition of the Natives in Western Australia headed by Dr. Walter Roth visited Beagle Bay. The timing was bad for Beagle Bay - at the mission were diocesan priest Fr. Russell, the secular teacher Mr. Randle, twelve Brothers and presumably a reluctant Fr. Walter. The missionaries looked upon the cattle herd as the surest way of growing their assets, rather than as a way of improving the lifestyle of the residents, and the mission residents took the opportunity of an official visit to air their views about the food rations, particularly the scarcity of meat. (Br. Wollseifer, too, felt in his dying months that he was left to starve and craved for some pork.81

Entering into the pearling industry had gained the Pallottines enemies in Broome, where many felt that it was the job of a mission to train and supply labourers, not to employ them in competition. Sergeant John Byrne from Broome told the Royal Commission that Beagle Bay was more of a ‘squatting business’ than a mission.82 It was certainly funded more like the ration depot of a squatting business than a mission. But the situation at the mission in 1905 could not inspire confidence.

The Roth report does not have a single word of praise for the German mission, one of only four missions in the State. New Norcia earned the attributes ‘flourishing’, ‘excellent’ and ‘worthy’, and Hadley and Hunter's private trepang station at Sunday Island, also receiving a subsidy for its school, was ‘a fine example’. All the report had to say about Beagle Bay was that its resident population had dropped by half, possibly because of the lack of food, that there were no Sisters, that mission residents should not qualify for the government payments for indigents, and that in future the ‘Lands Department should protect the interest of natives when issuing title to land’ to missions. It read like a slap in the face.

The government clearly disfavoured Beagle Bay mission in comparison to others. From 1896 to 1899 the Beagle Bay Trappist mission had received nothing while New Norcia had a fixed grant of £450 and the Anglican Swan home received £719. In 1899 it received £150 for 40 children whereas the Swan home was funded with £707 for 38 children. In 1900/1901 it received £250 for 37 children, whereas the Anglicans at Swan Home were paid £718 for 40 children, and New Norcia, with 64 children, still held its £450 subsidy.83 Effectively in 1901 a child at the Swan Home was funded at £17, at New Norcia at £7, and at Beagle Bay at just over £6, and any of these removed children cost the State less than a prisoner in goal. In May 1904 the government reluctantly agreed to increase funding for children removed to missions to the same level paid at the Swan Home and for other destitute children, though pointing out – inexplicably - that it ought to be cheaper to maintain children at Beagle Bay.84 On the same assumption the Roth report advised against funding sick and destitute persons on the mission at the normal rate of nine pence per day.85

There was tension on the mission sadled with debt. The Superior Fr. Walter, from a wealthy background and used to certain comforts, did not have the support of the Brothers.86 Trouble between him and gardener Sixt erupted into Sixt slapping the priest, and Walter retaliated by ‘excommunicating’ Sixt (presumably this meant barring him from holy communion). When the Trappists pressed for payment of their promised instalment that year, the Pallottine General Superior Kugelmann suggested that they could take the whole mission back.87

In about March 1905 Fr. Joseph Bischofs

A foreign priest who stood in for us here for a while drank well over his thirst, for two weeks the fellow was walking around here, of course an annoyance like that does not settle for a while. The schoolmaster was worse, but I had him sent away directly. P. Russell is sitting around at Beagle Bay now and do you think that the mission can prosper under such circumstances? I don’t think so.88

Little wonder that the Roth commission had been less than impressed. More Pallottine Fathers were urgently needed.

After that change happened quickly. Fr. Bischofs was appointed superior of Beagle Bay in March 190689 and he was naturalized in 1907.90 Br. Wesely had left for America by March 1906, Brother Bernard Hoffmann was sent to Kribi in Africa, and Br. August Sixt was expelled in 1906. This left nine Brothers: Matthias Kasparek (1901-1930), Johann Graf (1902-1951), Rudolf Zach (1902-1914), Matthias Wollseifer (1903-1952), Albert Labonte (1903-1912), Heinrich Krallmann (1904-1951), Anton Helmprecht (1904-1939), Franz Stütting (1904-1909) and Alfons Herrmann (1904-1909). Fr. Walter was back in Broome, Fr. Emo had made himself mobile and left Broome to Fr. Walter, Fr. Janny had moved the whole Disaster Bay outstation to Lombadina and then left Australia, and Fr. White had moved to Perth. They still needed one more to make up the apostolic 12 required by Bishop Gibney, and the mission needed a resident assistant priest. Fr. Thomas Bachmair arrived in February 1907. He was four years older than Fr. Bischofs and had thought he would be placed in charge. But he had little English and felt sidelined and purposeless for years.

Now things looked more prosperous and Fr. Walter wrote it would be ‘a pity to give up the mission’. With a government subsidy, donations from the Cardinal in Sydney, and its own income stream from by now 2,500 cattle, the mission ‘will soon be able to pay off debts and will be ‘able to give financial support to Limburg in the future’.91 Walter had embarked on an Australian fundraising tour with Fr. White and collected about £1,000.92 However this was less than the debts Fr. White had run up for his building projects in Broome and Perth.93

The arrival of the first nine St. John of God Sisters in May 1907 strengthened the mission. They were greeted with a big welcome, stepping through an archway covered with 'everlasting ' and 20 or 30 men decorated with cockatoo feathers dancing a corroborree. Most residents had never seen white women and the Sisters exuded an air of a different womanhood. Paddy Djagween and Lawrence Clarke recalled:

‘When the Sisters arrived, we all thought it was something different, of a womanhood which they thought it was hard to explain, but it was true, what they really thought was, it was a woman all closed in close, covered in, it was a very curiosity.’94

The government granted a lump sum of £500 and began to send girls to the mission. By 1909 the number of children had doubled from 50 to 94.95 In 1908 the Sisters received reinforcements and five of them established a convent in Broome, leaving six at Beagle Bay.96 The Irish nuns were not nearly as compliant as the Fathers wished and Fr. Bachmair, who had now become mission rector, ‘watched his beard grow grey’ from constant battles with the Mother Superior:

'Difficulties everywhere, lack of funds, dissatisfaction, difficulties with the Sisters who don’t want to be reasonable, especially the Mother Superior who constantly strives to find something to accuse us of. She seems to be one of those who can’t let us live in peace.' 97

The Provincial in Limburg watched these difficulties with growing concern. Despite the mission subsidy, relief for ‘indigents’ and subsidies for removed children, the mission was running up a shortfall of £500 every year and ran up a debt of £950 with the Broome stores. 98 Meanwhile Fr. Walter returned to Europe.

Fr. Wilhelm Droste, Fr. Theodor Traub and Br. Matthias Bringmann arrived in February 1909, accompanied by the Limburg Provincial Fr. Vinzenz Kopf, who paid a surprise visitation to the Kimberley mission. Part of Kopf’s intention was to settle continued disputations with the Brothers, particularly with Sixt, who was being 'obstinate'. Sixt was 'ordered off the mission' (although he had already left) and Brothers Franz Stütting and Alfons Herrmann, who had both arrived in 1904, were also repatriated to Ehrenbreitstein and Limburg respectively. The three new arrivals restored the equilibrium of twelve, and were to be the last consignment for twenty years.

Fr. Kopf’s other intention may have been to assess the case for a separate vicariate.99 Fr. Walter had gone to Europe in 1908 with this purpose in mind, to achieve a separate vicariate, like New Norcia. As it became clear that he was going to be neither a Vicar Apostolic nor a Bishop, he stayed in Germany in semi-retirement. The Benedictine Abbot Torres was appointed to this position in May 1910. Both Kopf and Walter in Germany were now pessimistic about the mission. Fr. Kopf felt that the Beagle Bay missionaries would probably never be able to clear their debts and told them they had to make money. The Brothers and Fr. Bachmair embarked on lobbying by writing personal letters to Fr. Max Kugelmann, their former Provincial Superior in Limburg (1894-1903) and former General Superior of the Pallottines in Rome (1903-1909). They begged Kugelmann for support to continue the mission.

A new era, 1910

Fr. Walter did not intend returning from Germany, and the Brothers sighed with relief.100 In 1910 Fr. Bischofs became the superior in Broome replacing Walter, and Fr. Bachmair became rector at Beagle Bay. Having the Sisters and three Fathers made a noticable difference to the mission life, which no longer revolved primarily around digging the mission out of debt.

|

| Old Rudolph Newman in front of the Bishop’s lodge at Beagle Bay, 1995. Photo:Regina Ganter |

One of the boys who arrived in that year, Rudolph Newman (aka Rudolph Roe), estimated to be age 10, became the oldest resident in the community, still there to celebrate its golden anniversary and beyond. Still extant sound recordings from 1910 include the school choir's rendition of ‘Der Fürst des Waldes’ in Nyul-Nyul and 'Wacht am Rhein' in English, three German songs and singing to accordion accompaniment. There are also recordings of speech from Felix Gnodenbor (or Gnodonbor), snippets of conversation, and traditional songs including a welcome back and songs by the Disaster Bay and Dampierland people.101

There was also a change of guard in the government. On 15 July 1910 Fr. Bischofs accompanied the Chief Protector of Aborigines Charles Frederick Gale, appointed in 1908, on his first visit to Beagle Bay, and the government attitude towards the mission changed dramatically. Gale misreported the history of the mission as having commenced with ‘14 Trappist monks supervised by Fr. Walter and White’, and claimed that it was now staffed with four Fathers (actually three on the mission), 12 Brothers (actually 8, but altogether 12 Pallottines), and 6 Sisters, but he gave a vivid impression of Beagle Bay mission in mid-1910:

'the usual bush wireless telegraphy had been working, for our arrival was not unexpected, and no sooner had we entered the mission gates than there out-bounded from the school-house two-score or more of the merriest and happiest looking native children from ten years of age downwards than it has been my lot to see. And what a warm and hearty welcome they gave the Rev. Father and myself! It was very pleasing to see such a bond of good-fellowship existing between the boys and the Superior of the mission, and indeed this same feeling between all the native inmates of both sexes and those who are looking after their welfare was very noticeable during my visit.102

Gale found the mission children ‘apt pupils’ with ‘a wonderfully good ear for harmony’, reciting ‘national and other songs’. He noted the ‘earnestness and zeal’ of the staff and found they were doing ‘really good work’. The Sisters taught 94 children ‘divided into different classes and standards’ in the mornings.

'I made a short examination of the different classes and was agreeably surprised at the brightness and intelligence of some of the scholars, the method of teaching being the same at Beagle Bay as at our State schools.'103

Gale also watched with interest how dexterously some of the older boys operated a circular saw driven by a 16 hp engine. They were being ‘taught different trades such as carpentry, blacksmithing, and tailoring etc. under the tuition of the Brothers, who are each masters of the trade which they teach.’ (This may be true, but their German trade qualifications were not recognized in Australia, and therefore the Brothers could not turn their apprentices into qualified tradesmen.) Meanwhile the Sisters taught household duties and sewing to the older girls, who produced ‘most of the clothing of the establishment’. 104

The mission reminded the Chief Protector of an Italian village, with substantial buildings of cajeput tree (tea tree), including a church, school, convent, dining hall for priests and Brothers, and dining hall for residents, where girls and boys had separate tables and indigents gathered at one end for meals. The dormitories were large and ventilated with cement floors, one accommodating 40 girls and a Sister in charge, and the boys’ dormitory that also accommodated the Brothers. The other Sisters shared a room next to the room for indigents and sick. Some former mission boys had become native assistants, and were settled in stone cottages with their wives.

There were also butchers, bakers, blacksmiths, and carpenters shops, cart sheds, and chaff houses, and the Chief Protector estimated the total value of buildings at £16,000 (which was later annotated: ‘too much?’) and the value of land improvements, consisting of wells, windmills, bores, and fencing, valued at £2,000 (also later annotated with a large question mark). The gardens produced a ‘plentiful supply of vegetables’ supplemented by coconut, date and orange trees. The stock was estimated at 3,500 cattle, though the land, mostly pindan, was not considered good grazing land, and not even the Director of Tropical Agriculture had been able to think of a marketable crop that would grow on the swampy and springy land. 105 Sisal hemp was tried shortly afterwards, as at Cape Bedford in Queensland. The Chief Protector noted that the whole establishment was heavily subsidized from Limburg. The only unresolved question, which occupied the missionaries and the Protector, was what would become of these well-trained children after they finished their schooling? 106

That year the Pallottines were offered Lombadina. Lombadina was a Filipino/Aboriginal community with a group of Bardi people that had been for some years under the supervision of the Sunday Island pearlers Hadley and Hunter as a government feeding station. A cloud of suspicion gathered over Hunter and Hadley’s relationships with Aboriginal women, and after his visit to Beagle Bay the Chief Protector asked the Pallottines to take on Lombadina. The Pallottines now had three priests at Beagle Bay and one in Broome and were in good shape for expansion. Fr. Theodor Traub and two Brothers were sent to Lombadina on the mission lugger loaded up with provisions and were caught up in an unseasonally early cylone:

'The cyclone on 19 November 1910 is probably Broome's most destructive event when winds were estimated to reach 175 km/h. Forty people died, 20 houses were destroyed, another 70 badly damaged, and 34 pearling boats wrecked or lost.'107

The Beagle Bay mission pier was demolished and the lugger damaged108. Rector Bachmair sold the Leo and was glad to end the pearling experiment, which seemed more like a gamble than an income source, though soon after the pearl-shell prices at Broome soared to £230 per ton as a result of shortages. Bachmair was overwhelmed by all the help offered after the cyclone. The government transferred £500 as disaster relief, Cardinal Moran sent £100, a collection in Perth brought £49. This covered the damage and paid for a 29-ton ex-government schooner (£353 including delivery and repairs), the Namban. 109 Fr. Emo helped out with his San Salvador until the new schooner arrived.

Fr. Traub was severely shaken by his cyclone experience.110 Fr. Bischofs wrote in January 1912 that Br. Albert Labonte and Fr. Traub had left the mission (one to Ikassa, the other to Duala in Cameroon), but the others were ‘ready to continue at Beagle Bay’.111 Fr. Bischofs felt that the Lombadina outstation could be served by regular visits but it had a shaky start until Fr. Emo, who had made himself scarce since his clash with Fr. Walter in Broome, was invited to oversee Lombadina and formally took office on 1 January 1911. He brought several Cygnet Bay people with him and the Lombadina settlement grew quickly under his reputation.

While the Kimberley missionaries were in an expansionist mood, their General in Limburg was casting around for ways of withdrawing, still driven by the concern about money.

'One day Fr. Th. Bachmair came to us really depressed and reckoned the Limburgers want money, we were to make money one way or another, if I’m not mistaken they wanted £400 a year from us. The rector decidedly refused this since we were still over the ears in debts, and a few months later, February 1911, the decision to give up the mission arrived.'112

But no other Catholic order wanted to take over the Kimberley mission. Br. Kasparek narrated that the Steyler missionaries took over instead a mission from the Jesuits in Dutch East Indies at Kupang and the Sumba Islands, and the Sacred Heart Missionaries in Sydney politely declined.113 They had been given the Darwin diocese and were just beginning a mission at Bathurst Island.